The Death Of Christendom: The Slow And Painful Destruction Of Christian Civilization

By Theodore Shoebat and Walid Shoebat

The life of Israel is the life of Christendom. As Israel once broke apart — with Judah and Israel splitting — so Christendom broke apart, with the Avignon controversy — in which Europe was split between those who believed that the Church was to be stationed in France, and those who held the orthodox view that it was to be in Rome — and then the Protestant revolt which led to even more fragmentation, and then eventually erupted into out right conflict that put Christendom through a slow and bloody death.

This is beginning of a series that we will be working on, entitled The Fall of Christendom, which will go into many of the details on the story of Christendom’s death.

PART 1

The fall of Israel did not come about because of the Romans, but because of the rejection of the Messiah. Likewise, the fall of Christendom did not happen because of Muslims or pagans, but rather because of Christians who left the sheepfold of the Church and warred against the Messiah’s representative on earth, the Church.

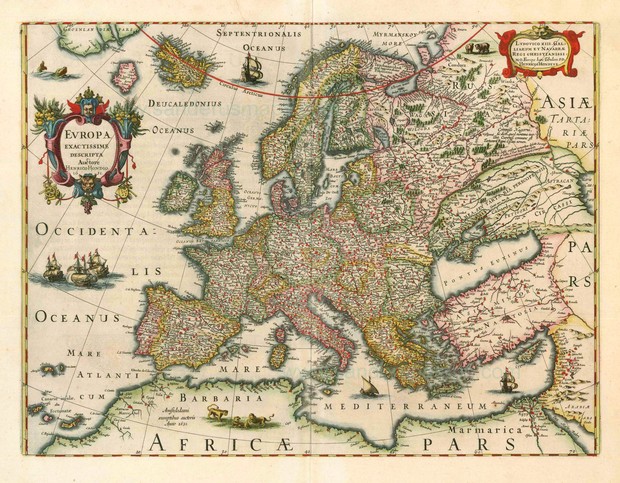

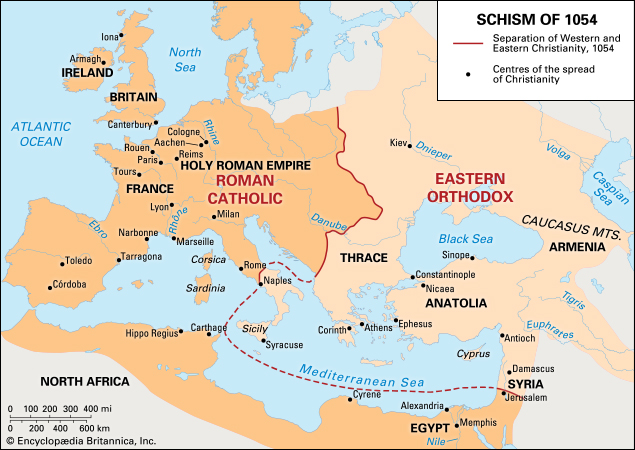

Christendom (Christianitas or Corpus Christianorum) was a term that signified nations unified by belief and creed within the Catholic Church. The breakdown of Christendom began in 1054, when the Eastern Church split from Rome, and the Pope and the patriarch of Constantinople mutually excommunicated each other. From that time onwards, Christians under Rome were severed from Christians under Constantinople in Russia, the Balkans and the Greek archipelago, and thus formed western Christendom. The East-West Schism of 1054 was amongst the marks beginning Christendom’s death.

In the history of Christendom, one sees, not a perfect utopia, but a continual struggle between Christendom and Europa. Christendom — the body of nations united under one faith, one baptism and one God, in which the State and the Church work in harmony to advance and protect the religious vibrancy of the Catholic Fatih — was always in bitter conflict with Europa, a body of nations that look out for the interests, not of Church or dogma, but of their own nationalist egoisms. The fall of Christendom was preceded by in-fighting, that began in the ecclesiastical realm (Catholic theology versus Protestant theology) and ended in the battlefield (the civil war in Switzerland, the Wars of religion, etc.) culminating into the Thirty Years war in the 17th century that utterly fragmented Europe under the corpses of millions. With the death of Christendom, came the emergence of Europa, with a geographic location — Europe — and its nations each doing what it pleases.

One cannot speak of the death of Christendom without discussing the fragmentation of western Christendom that occurred from 1378 to 1417, called the Great Schism, which split Christians between those who were loyal to Rome and those who pledged loyalty to Avignonese papacy in France, which was merely ran by an anti-pope who, in wanting to sabotage the Roman papacy, was merely a puppet in the hands of the French monarchy.

Nationalist rivalries between Italians and the French were beginning to manifest strongly even within the Church. For example, in the 14th century, in the College of Cardinals, which consisted mainly of Italians and Frenchmen, when cardinals voted for a pope, they tended to vote for people of their own nationality. In the late part of the year 1277, the College of Cardinals was made up of only seven people (the smallest in its history), four Italians and two Frenchmen.

Since the Italians were in the majority, they elected a fellow Italian, Giovanni Gaetano Orsini, a man from the prestigious Orsini family of Rome, to be Pope, and he became Pope Nicholas III. In March of 1278, Nicholas III chose nine new cardinals, six of whom were Italian, and the rest was one Englishman, one Portuguese man and one Frenchman.

Following his papal duties, Nicholas III worked to maintain peace between kingdoms that wanted to kill each other. He ordered Rudolf I, Emperor of the Hapsburg Dynasty, to not make war on the French King Charles of Naples and Sicily, and to withdraw his claim, and all of his military garrisons from the region of Romagna in the northern part of Italy. Nicholas III also told Rudolf I to relinquish his office as Senator of Rome. Rudolf I, loyal to the Pope, agreed to these requests.

Pope Nicholas also had to deal with rising political and theological tensions in Constantinople. Much of the Greek clergy were opposing the theological agreements that were made between Constantinople and Rome under the auspices of Pope Gregory X in the Council of Lyons. Michael Palaeologos accepted a reunion between the Eastern Church and Rome. Pope Nicholas III understood that the reason why Michael agreed to this reunion was to get the Church’s protection from King Charles I of Naples who wanted to invade Constantinople.

The Patriarch of Constantinople, John Veccos, agreed on the Catholic Church’s position on the Filioque — or the declaration in the Roman version of the Nicene Creed that the Holy Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son (as opposed to the Orthodox version that states that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father) — was correct. Pope Nicholas III accepted Vecco’s agreement as sincere.

On October 1278, Pope Nicholas III gave the Catholic Church’s ambassador to Constantinople, Bishop Bartholomew of Grosseto, a set of statements and instructions to give to Constantinople. In this message, Pope Nicholas III praised the Emperor Michael and his son for their support of the union between the Churches of East and West, he also urged the Greek bishops to recite the Nicene Creed with the Filioque at every Sunday Mass, and to also sign a confession of faith with the Filioque in it. But the Pope, with prudence, also cautioned not to push the eastern bishops to sign the confession of faith if tensions were too intense.

To further prevent conflict, Pope Nicholas III summoned a peace negotiation between the Emperor Michael and King Charles. Michael, knowing full well that Charles was thirsty for conquests, wanted with great desire this peace deal. But the Emperor Michael, while wanting to maintain good relations with Rome, also desired to keep favor with the Greek bishops who hated the theological agreement with the Catholic Church. Michael removed John Veccos from his position as patriarch in order to please the Greek church authorities. He also told Greek bishops, in a secret meeting, that he promised not to allow any more additions to the creed. However, the emperor also urged the bishops not make any sort of blatant protest to the Pope.

When the papal ambassadors arrived, Michael made John Veccos patriarch again, and the Greek bishops assured them that they were in agreement with the theological reunion between Constantinople and Rome. Pope Nicholas III accepted these guarantees, and continued to prohibit King Charles from attacking the Byzantine Empire.

In the year 1280, in the month of August, Pope Nicholas III, suddenly collapsed and died. With his death, whatever concord he had tried to keep, began to fall apart, and the war between Europa and Christendom — between nationalism and universalism — reemerged. Nicholas III, being of the prestigious Orsini family in Italy, was greatly hated by the Annibaldi family and other anti-Orsini factions.

When the conclave of thirteen cardinals gathered together in the provence of Viterbo in September, they were split between pro-Orsini and anti-Orsini sentiments. The assembly were in an impasse, no side would agree, and this went on into January. When the month ended, the French King Charles began to expand his troops into Viterbo, where the Cardinals were gathered to agree on a new pope. On February 2, 1281, a town captain in Viterbo, named Rainer Gatti, who was of the anti-Orsini faction, led his militia and stormed the bishop’s palace where the assembly of cardinals was taking place. The mob seized two pro-Orsini cardinals and cast them into prison.

They took another pro-Orsini cardinal, Matteo Rosso, and kept him hostage until a new pope was elected. Now that the pro-Orsini cardinals were a minority in the conclave, being only four in number, while the other side had eight, the anti-Orsini faction quickly elected the French cardinal, Simon de Brion, a lover of all things French, and a very close associate to King Charles. Simon de Brion took the name Martin IV and the papal tiara was crowned on his head.

On July 3rd of 1281, there was a meeting that took place in Pope Martin’s residence in Orvieto (presumably in his presence), between King Charles of Naples and his son-in-law Philip of Courtenay, in which they signed a treaty agreeing to the conquest of Constantinople. Pope Martin, indicatively, agreed to this treaty, which declared:

“… the exaltation of the Orthodox [Catholic] faith and the reintegration of the Apostolic power, which through the loss of the Empire of Romania [Byzantine Empire] (removed from obedience by the now ancient schism), has experienced severe maiming in the mystic body of church unity … [and also] for the recovery of the Empire of Romania, which is held by Palaeologus.”

Whatever peace that Pope Nicholas III was trying to maintain was being reversed by these autocrats. With Pope Nicholas III now deceased, the French had gone unhinged. Pope Martin IV excommunicated the Emperor Michael, calling him a “supporter of the ancient Greek schismatics” and deriding him as a man “called Emperor of the Greeks.” Yes Michael Palaeologus’ conversion to Catholicism was questionable, but nonetheless we cannot blame him for declaring himself Catholic. After all, he needed the protection of the Church from the rapacious King Charles. And we know that the Greek patriarch, Veccos, did have a sincere conversion. Pope Martin IV further advanced Charles’ power by giving him the title of Senator of Rome.

Charles’ plan to invade Constantinople reached the King of Aragon, Peter III, who wrote to the Italian city of Pisa requesting reinforcements against the French king in his own kingdom of Sicily:

“You know, of course, that the wicked and impious Charles intends shortly to attack the Emperor of Constantinople, united to me by a bond of recent friendship. I have decided in my heart of hearts to oppose the presumptuous daring of this king with firm disposition and with all my power. For I intend…. to enter the Kingdom of Sicily and there to establish myself… with a large force of my men. And thus, while that king will believe fictitiously that he has conquered the Greeks, the Sicilians will find themselves irrevocably subject to my rule.”

In the middle of March of 1282, Charles assembled his fleet in the Sicilian harbor of Messina, in order to make the initial attack against Constantinople. On March 29th, Easter Monday, some of Charles’ French troops were around the Church of the Holy Spirit where thousands of Sicilians were gathered around to celebrate the holiday’s festivities. The French troops were acting haughty and presumptuous around the native Sicilians. One of the soldiers, Drouet, grabbed a Sicilian woman and dragged her away from her husband, who was so enraged that he unsheathed a dagger and stabbed Drouet to death. The other Sicilians went into a rage and killed every French person they spotted, sparing neither man nor woman. The slaughter was great, around two thousand people were butchered. The event is known as the Sicilian Vespers.

News of the massacre reverberated throughout Christendom, with details of carnage and savagery disturbing all who heard of it, including the Pope who was, actually, a gentle man. Pope Martin IV suspected that Michael Palaeologos conspired this massacre (although there is no evidence to prove this) and renewed his excommunication. Pope Martin IV also demanded that every Sicilian submit to King Charles or else suffer excommunication.

The Sicilians, through an ambassador, offered their submission to Peter III of Aragon, to be ruled under him. While Charles was planning to invade Constantinople, he now had to deal with a Spanish invasion of his island of Sicily. In July 25th of 1282, Charles and his forces stormed the beaches in Sicily and then made his attack on Messina to retake the city. The Sicilians defeated Charles, repulsing the French five times in a row. On August 30th of that year, Peter III of Aragon entered Sicily with his navy and went into the city of Palermo where he was given the crown and declared king. Now Charles had to deal with both the Sicilians and a Spanish military. He was not strong enough to deal with a combined force. The French and Spanish navies clashed in the seas, with Peter’s fleets vanquishing Charles’ warships in two victories. The Spanish and the Sicilians had won, and Charles’s invasion of Constantinople could not be done in that time.

Pope Martin IV later excommunicated King Peter III of Aragon for his accepting of the crown over Sicily. Martin went so far as to declare a crusade against Peter, and exhorted Edward the Longshakes of England to end his daughter’s engagement to Peter’s son, Crown Prince Alfonso. Pope Martin went further in his cause against Peter. He called upon the French clergy to give tithes for three years for a crusade against King Peter III of Aragon. And in January of 1284 he ordered the Archbishop of Genoa to recite in his cathedral the declaration of the Pope against Peter III of Aragon, and to warn the Genoese that they were, on pain of excommunication, not allowed to have any dealings with Peter.

People in Rome were enraged. A horde of the pro-Orsini faction, alongside other adversaries of the Pope, stormed the Capital building in Rome and slaughtered the French troops who were stationed there. Chaos was rising within Christendom, and nationalist enmities between French people and Italians was manifesting into outright mob violence.

Meanwhile on the waters of Italy, the Italian general, Ruggiero di Lauria, one of the most successful naval commanders in Medieval history, fought for the Spanish kingdom of Aragon and crushed the French navy of King Charles in the Bay of Naples, and even captured his son, Charles II. On January 7th, 1285, King Charles died and his son, Charles II, was kept in captivity. The French, enraged at the Italians, wanted to execute a full scale invasion of Aragon. Pope Martin IV was in full support of the invasion and exhorted James, the king of Majorca, to partake in the war.

On March 28th, 1285, Pope Martin suddenly died of a fever. His successor, Giacomo Savelli, was elected Pope in April of 1285, at the age of 75, and took the name of Pope Honorius IV. During his short pontificate, the French invaded the Spanish kingdom of Aragon. King Peter III of Aragon fought in hand to hand combat in the struggle to fight off the French, but was struck dead by a mortal wound. King Philip III of France, after vanquishing the Aragonese city of Girona, ordered him army to withdraw on account of the spread of dysentery in the camp. On their way back, a huge amount of the French troops were either killed or scattered while fighting with the Spanish in the Battle of the Col de Panissars in the Pyrenees.

Not too long after this tragedy, King Philip III died, and his son, Philip IV le bel (“the fair”) succeeded his father’s kingdom. After the death of Philip III of Aragon, his eldest son, Alfonso III, succeeded him and took the throne, and his younger son, James, was crowned as King of Sicily and Palermo in February of 1286. Pope Honorius IV quickly excommunicated James, his mother and also all of the bishops who were involved in his coronation. Honorius agreed to an armistice between France and Aragon, which took effect in August of 1286, although he refused to agree to any concessions or settlements between the two kingdoms, leaving Sicily under the power of Aragon, and Charles II in prison.

In 1287, on Holy Thursday, Pope Honorius died of a stroke. The Conclave of Cardinals, which had only had fifteen cardinals, convened together to vote for a new pope. The cardinals reached a heavy impasse when they could not agree on a pope, a dilemma that went on for months into the summer. During this time, six (or possibly even seven) cardinals died, the largest amount to die in a conclave in the history of the Church. Because the seat of St. Peter was vacant, the surviving cardinals were asked to mediate in certain political situations.

The first was to adjudicate in the peace meeting between Alfonso III, the new King of Aragon, and Charles II (who was still in prison). The peace negotiation was also mediated by Edward the Longshakes. The peace agreement provided 50,000 silver marks, and stated that Charles II would be released from prison, and that his three sons would be kept as hostages in his place. Charles II was to work for peace with Aragon for three years, and if peace was not established he was to be returned to Aragon as a prisoner or give up the regions of Provence to the kingdom of Aragon. The peace deliberation was concluded with the Treaty of Oleron. The cardinals, reluctantly, agreed to this. However, King Philip IV vetoed it without giving his reasons.

The Church truly was losing its grip over the governments, and Christendom was giving way to Europa. This truly was revealed to a Christian monk from China named Rabban Sauma, who visited the European countries after he was sent as an ambassador by the Mongol Il-Khan Arghun of Persia. Once he arrived in Naples in June 1287, he “who had come to Europe thinking to find Christendom ready to unite against the Muslims of the East” was faced with the leviathan of nationalist Europa. Sauma himself witnessed a battle in which the navy of Ruggiero di Lauria crushed the navy of Naples. Sauma traveled to Rome where he visited its splendid churches, he also met with cardinals who did not offer him much enthusiasm for his envisioned war of Christendom against the forces of Islam.

From Rome he travelled to France where he met with Philip IV who received him warmly, and who showed him the beautiful shrine of the Sainte-Chapelle, constructed by his grandfather, St. King Louis IX. Philip showed the Chinese monk little to no interest for undertaking a war against the Muslims. Sauma then sojourned to England where he met with King Edward the Longshakes who told the Chinese traveller that he could not make any promises about retaking the Holy Land from Islamic rule. Christendom was being torn apart by in-fighting on account of nationalist interests, and was thus becoming Europa.

This ends part one of our series on the death of Christendom. Get ready for part two, coming soon.

Comments are closed.