Building a state in the shadow of the Holocaust

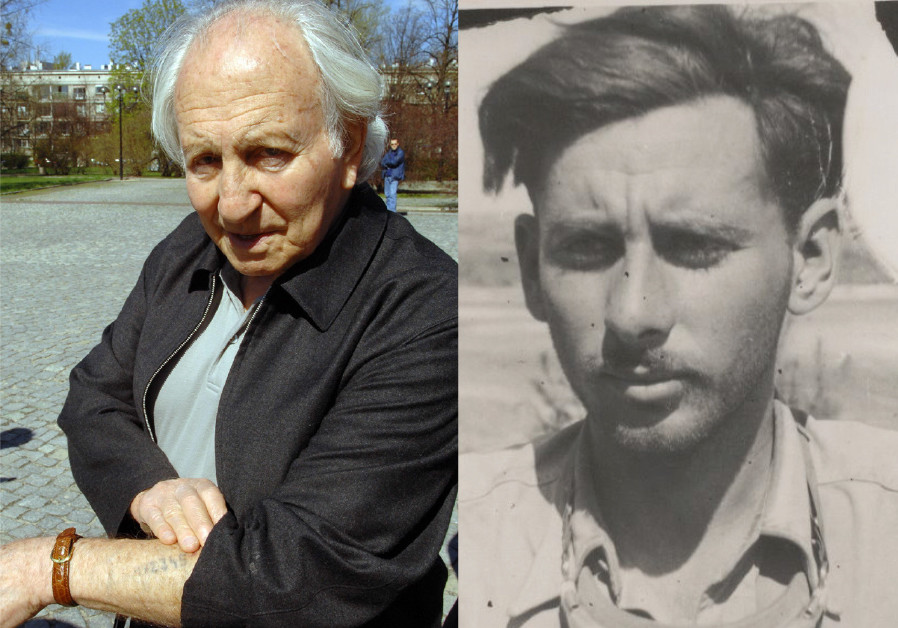

Left: NOAH KLIEGER shows his Auschwitz number tattoo. Right: URI AVNERY in his army uniform from the War of Independence in 1948. (photo credit: GPO/WIKIPEDIA)

Some moments in history are so decisive, they remain etched in our memories forever. Uri Avnery remembers the moment of Israel’s declaration of independence precisely because it struck him as inconsequential at the time.

Avnery, then a 24-year-old Hagana fighter, was busy preparing for an assault on an Arab village near Ramla when he was urgently called to the kibbutz canteen.

“We listened to part of [David] Ben-Gurion’s speech,” he recalls, “until we reached the only point that interested us: the name of the new state. The moment Ben-Gurion said ‘a Jewish state to be known as the State of Israel,’ we said goodbye and got back to work.”

That night, Avnery’s unit captured the Arab village. Israel was invaded by a coalition of Arab armies, and Avnery was transferred south later the same night.

“For a few fateful days, the only thing that stood between the Egyptian army and Tel Aviv was a few Givati companies; nothing more,” he says.

“We knew that we were in the middle of a battle for life and death,” he adds. “So there were no outpourings of celebration in Tel Aviv. That’s a myth. Those are stories made up later.”

He recalls having been woken up on November 29, 1947, by the sound of public celebrations after sleeping through the UN vote to partition Palestine. But on the day of the declaration of independence, the celebration was very small.

“We were,” he says, “all very worried.”

Avnery, now 94, went on to serve in the Knesset and be a pioneer of the Israeli Left.

“As far as we were concerned, there was no importance to Ben-Gurion’s speech,” he recalls. “We knew that the state would be established if we won, and wouldn’t be established if we didn’t win, and it wasn’t obvious at all that we would win.”

He felt a genuine fear that the nascent state would not survive, but it won because its fighters had their backs against the wall.

TWO THOUSAND miles away, Noah Klieger was desperately trying to reach the Promised Land. A survivor of Auschwitz, the 21-year-old Frenchman was stranded in Belgium because the ship he had hoped to board to Pales- tine never reached Marseille. He heard Ben-Gurion’s speech with a delay because the radio in Antwerp did not carry the speech live.

The news did not come as a surprise to him because of the UN partition vote months earlier, but the occasion was nevertheless momentous.

“I was so happy, I could have kissed everyone, even in the street,” remembers Klieger, now 91.

He departed for Genoa the next day to board a ship to the newborn Jewish state, but waited for three weeks to make aliya with 200 other Jews because boats could not dock in Israel until the first cease fire.

One year after being turned back from the shores of Palestine by the British aboard the Exodus, Klieger was home in the Jewish state. And only three years after facing imminent death at Auschwitz, he was fighting for his survival again, having been recruited as an infantry soldier on arrival.

He did not have a gun for the first few months, until there was weapons shipment from Czechoslovakia. Fighting alongside other Holocaust survivors in a Palmach unit established by a French commando, he fought in Ramla, Lod and Beer Sheva, going as far south as Eilat after its liberation.

“This time, I was not fighting for my [personal] survival,” he stresses. “I was fighting for the survival of the Jewish nation, for the future of the Jewish nation.”

Unlike Avnery, however, Klieger never thought Israel might not survive the Arab invasion: “I realized when I was in the war that the [native] Israelis, together with the 120,000 newcomers, would never give up. We were going to win the war because we had to win the war.”

THE STATE of Israel declared independence on May 14, 1948, three years after the end of the Second World War and the liberation of the camps in Europe. In later years, Israelis would connect the two events on an indivisible continuum, interpreting the state’s establishment through the lens of “from destruction to resurrection.” But at the time, Avnery recalls, the Holocaust did not loom as large as it does in hindsight.

“The truth is that people didn’t think about the Holocaust or the Jews in Europe until the Soviet army captured the first extermination camp,” recalls Avneri, who had fled Nazi Germany with his family in 1933..

During the war, the Yishuv (Jewish community in Palestine) was more preoccupied with a possible German invasion than whatever was happening in Europe. They knew of a Holocaust but did not believe the stories yet. And the Jews of Palestine were so single-mindedly focused on independence, Avnery says, that once it was clear the British would leave, they thought of nothing else.

“It was a very heavy blow to the Yishuv,” he recalls, speaking of the first reports from the death camps. “But the Yishuv was already busy with the war against the British…. The Holocaust played a much smaller role in our consciousness in Israel than it seems today. It was a difficult thing, a terrible thing, but less important than our struggle for independence.”

On reaching Israel, Klieger indeed found a gulf in understanding between native Israelis and Holocaust survivors.

“They didn’t know how to handle us. They called us ‘soaps,’” he says with a wry laugh, “because they heard that the Germans made soap with the fat of our victims – which is not true by the way.”

The influx of Holocaust survivors was a collision of two worlds. “They were a different people, they were a people born free,” he says. “For years, we were not free at all, but they were always free.”

For Klieger, the story of Israel’s rebirth was inseparable from the destruction of European Jewry.

“I became a Zionist in Auschwitz,” he recounts. “In Auschwitz, I realized that should I survive – and I was convinced I would not survive – I would become an active Zionist, helping to rebuild a new Jewish state after 2,000 years.”

Klieger also promised himself that he would make it his life’s mission to tell the world about the Holocaust. After Auschwitz, he reported on trials of Nazi war criminals in liberated Europe (“a farce”); in later years, he participated in an astonishing twenty-seven processions of the March of the Living in Poland.

ISRAEL HAS changed beyond recognition over the past 70 years – and these two veteran citizens could not be farther apart in their reactions to the change.

“If one of the fallen from 1948 were to rise from the dead and see the country today, he would go back to his grave,” says Avnery. “We wanted a completely different country from the one that was created.”

He complains of the death of the founding generation’s pioneering and volunteering spirit, decries the closure of the kibbutzim, and laments the failure of efforts to forge a radical, new, secular Hebrew nation.

“It’s a different society today; it’s corrupt, money-grabbing, every-man-for-himself, and it’s deeply divided,” he notes.

If anyone back then had predicted the manifold corruption scandals in modern Israel, Avnery says, they would have been considered mentally ill.

“Today, people use ‘elitist’ as a curse word,” he states. “But the whole Yishuv was elitist…. They wanted to create a completely new culture.”

Israel’s founding generation produced a veritable pantheon of artists, he argues, with no successors in modern Israel. But the change, he notes with sorrow, was inevitable, the unavoidable result of expanding a tightly knit ideological community to include “millions of immigrants from different cultures.”

Klieger paints a rosier picture of Israel’s health at 70: The Jewish state is such a success story, he says, that much of the hatred toward it is motivated by jealousy that it grew so strong so quickly.

“Israel has become one of the leading countries in the world,” he says, his eyes almost audibly glistening over the phone.

“No country in history has ever done it. We did it. Because we wanted to do it, and because we were forced to do it. We have never had a quiet day. We have developed a country that can be proud of itself in all respects.”

Eylon Levy is a correspondent and news anchor at i24NEWS.

Comments are closed.