Gregor: The False Dichotomy of Nationalism Versus Patriotism

Recently, the President of the United States stated that he is a nationalist. That sent tremors throughout the globalist and leftist academic community. Almost immediately, the President of France felt called upon to explain why his country cousins in North America should be disturbed.

We were told that there was every reason to be dismayed—that nationalism was “the very opposite” of patriotism. While we all feel patriotic on occasion, we are told that we should never ever feel nationalistic. It is not obvious why that should be the case, but it is affirmed by the authority of the President of France. Now, it is not at all clear that the distinction offered is true, and if true, how it was intended to help. At this point we can only undertake reasoned speculation.

French President Emmanuel Macron delivering a speech on November 11, 2018, during a ceremony in Paris for the 100th anniversary of the armistice that ended World War I. He used the occasion to rebuke U.S. President Donald Trump’s embrace of nationalism, stating “patriotism is the exact opposite of nationalism.” (Ludovic Marin/AP)

For most of us, the terms “nationalism” and “patriotism” are sufficiently similar to qualify as synonyms in most dictionaries. There is some suggestion that the one is a sentiment and the other is the sentiment in act. In effect, it is generally understood that one expresses one’s nationalism in patriotic acts. But the French President suggests something more than that. He suggests that each of these terms has an entirely different reference. Each refers to an entirely different something. One cannot be both a nationalist and a patriot—for the President of France, they are mutually exclusive. One is the opposite of the other. The President of France apparently knows something we do not.

The fact is that in the recent political history of our time, there were some who made that very same distinction. Foremost among them was Josef Stalin. It is a story worth the telling.

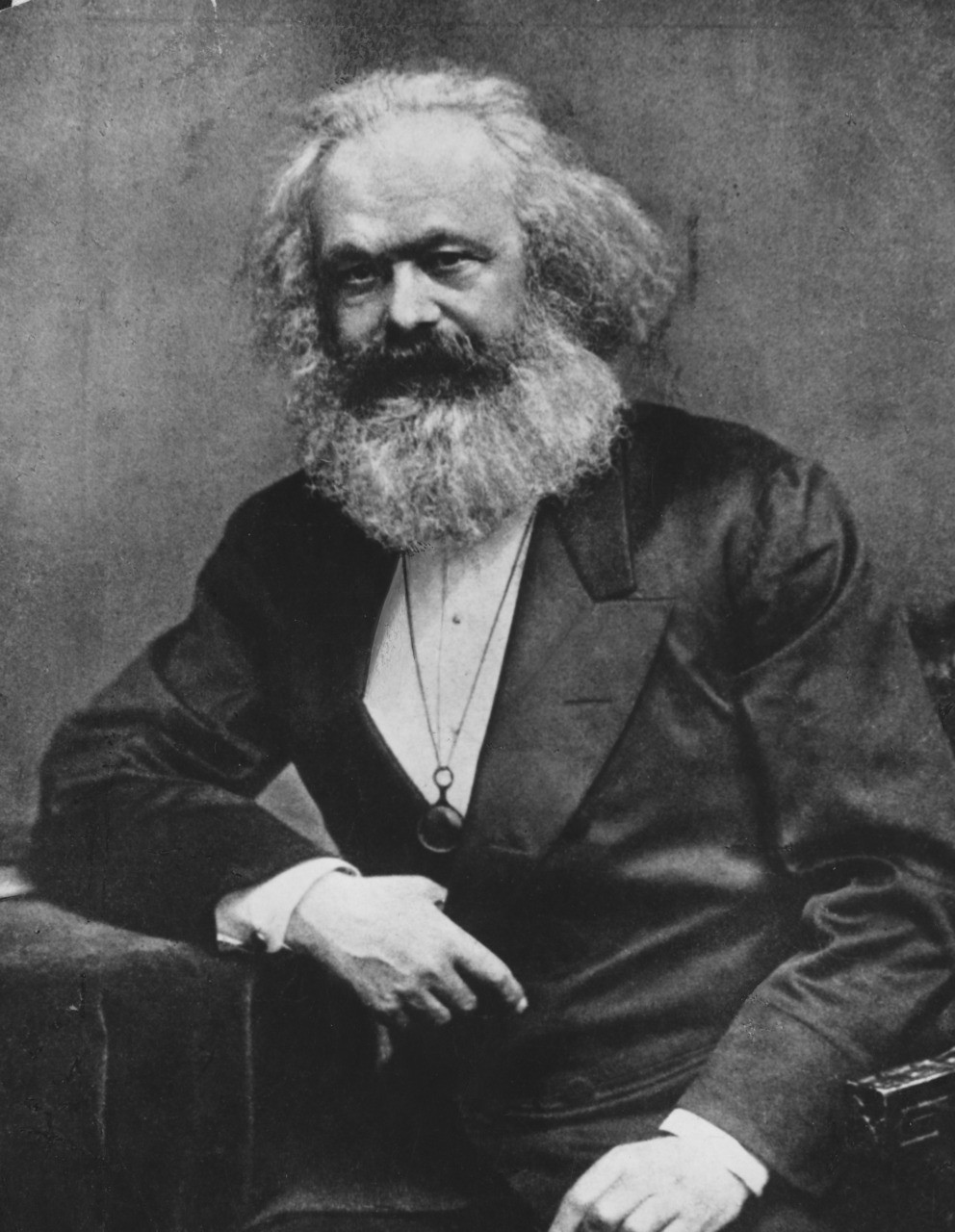

It seems that the founders of classical Marxism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, were convinced that nationalism was a transient sentiment that, at that time, teetered on the very brink of extinction. In the Communist Manifesto of 1848 we were told that the masses were no longer disposed to make recourse to nationalism—their sentiments were all universalistic. They were all globalists. Among themselves, they no longer dwelt on differences of language, or culture, or history, or descent, or territorial origin. They recognized only class identity. The agents of history were proletarians, and their sentiments were universal working-class sentiments. In 1848, Marx already saw nationalism as an anachronism, as a sentiment that inspired only reaction.

Unhappily, the proletariat, itself, was apparently not as intuitive as Marx—and with the outbreak of the Great War of 1914-1918, threw itself into the conflict without reservation—as waves of nationalist sentiment drove millions of young men to sacrifice and death on the battlefields.

Young men queue up to enlist at the Army Recruiting Office at Southwark Hall, south London, in December 1915, during World War I. (Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

The Marxists of the Second International, convinced that the proletariat had forsaken nationalism, had called on them to rise up against international conflict—to refuse to fight their brother proletarians. In response, the proletariat everywhere opted to support their respective nation in the conflict—and proceeded to fight their brother proletarians with unmitigated ferocity.

The bodies of hundreds of Italian soldiers lie dead on the battlefield, victims of a gas and flame attack during World War I. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Revolutionary Marxists were confounded. How were they to make a universalistic revolution when each national segment of the proletariat insisted on its own nationalism? Russia’s Bolsheviks saw nationalism as an obstacle to the mass mobilization of revolutionaries. As Marxists, they conceived nationalism a reactionary sentiment—dividing the working class into jealous enclaves against itself. They saw nationalism as a contrivance of the oppressing class, designed to frustrate the efforts at universal revolution. For revolutionaries, it seemed evident that simple membership in the working class was not enough to serve as a unifying inspiration.

Joseph Stalin and Vladimir Lenin address the proletariat during the Russian Revolution of 1917. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

What the community organizers of Bolshevism ultimately settled on was an appeal to patriotism—which came to mean disciplined obedience to the directives of the revolutionary Party. Since the Party came to control all of what had been Russia, obedience to the Party took on all the overt features of nationalist commitment. Ordinary Russians could feel loyalty to the territory, the language, the culture, and the history of Mother Russia—and call it “patriotism.” The Party could see in that expression of patriotism loyalty to the revolution, and to the Party. To Stalin’s communists, patriotism was welcomed as the exact opposite of nationalism. While nationalism parsed the working class into separatist national segments, patriotism was made to unite the proletariat into seamless obedience to the Party.

With the passage of time, Stalin used patriotism to mobilize unqualified support for his dictatorship. He had accepted the reality of his circumstances and declared that Bolshevism no longer anticipated imminent universal revolution—and in violation of every precept of classical Marxism chose to attempt the making of socialism “in one country.”

Since Marx had precluded the employment of nationalism as a means to mobilize revolutionaries, Stalin enjoined the masses to be “patriotic.” The masses were taught that they lived in a land that had given the world its most cherished cultural products. They learned that the land on which they dwelt should be defended with their lives. They learned that they were the future of the world—and when the Motherland was invaded, they fought “The Great Patriotic War”—at the cost of more than twenty million lives. Nationalism never demanded more.

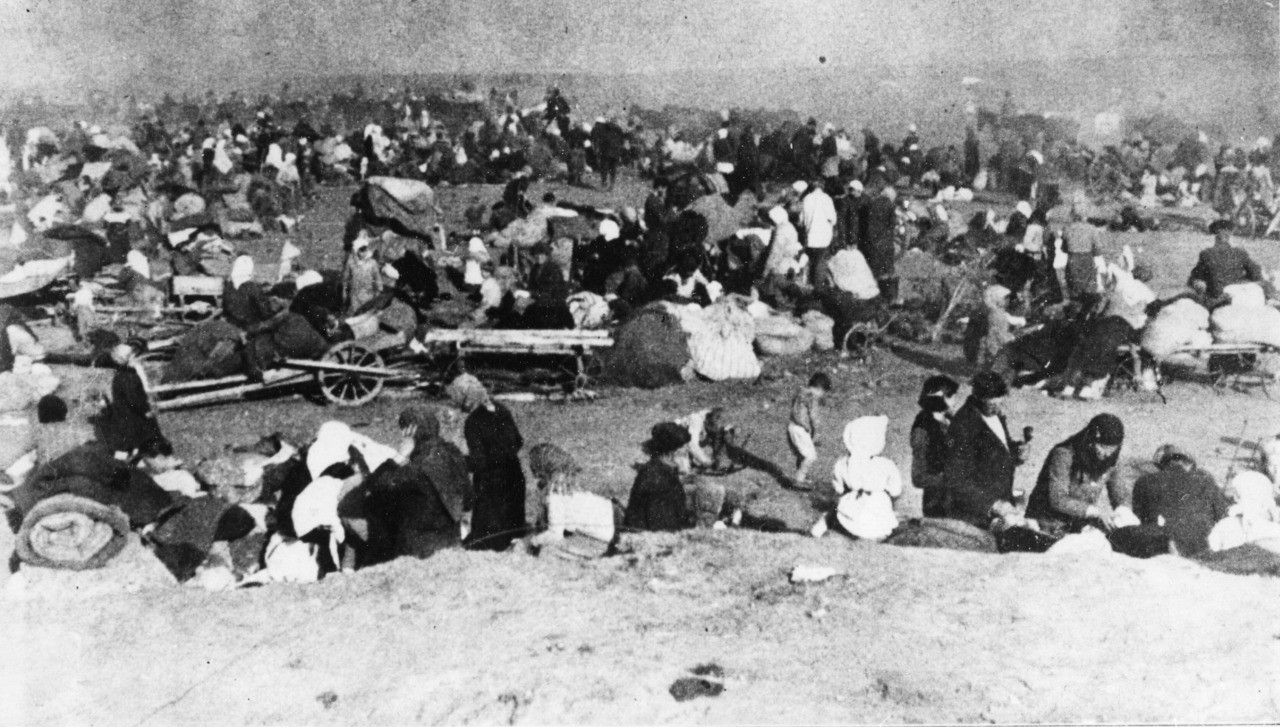

Women, children, and old men cluster on the outskirts of Stalingrad to escape the Nazi bombing in September 1942. (Keystone/Getty Images)

Red Army reinforcements arrive in Stalingrad to recapture the city from the German 6th Army, on January 22, 1943. (Keystone/Getty Images)

Soviet gunners fire at Nazis who had barricaded themselves into houses during street fighting on the outskirts of Stalingrad in January 1943. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

During much of the Cold War, France was the site of one of the largest communist parties in the West—and was noted as being particularly Stalinist in orientation—until Stalin was exposed by his own followers as being a singularly homicidal despot. French enthusiasm cooled. But the echoes of the involvement remain, and the President of France apparently still recognizes the Stalinist distinction between nationalism and patriotism he learned at university from his leftist professors.

In their time, the major communist parties acknowledged that same distinction. Patriotism supported the Party. Nationalism did not. Patriotism was the “direct opposite” of nationalism. Taking their lead from the Soviet Union, the communist parties of Maoist China and Pol Pot’s Kampuchea insisted that their populations be not nationalistic, but “patriotic.” Which meant that the masses be compliant, obedient, prepared to sacrifice, as well as defend the Party from all enemies in the geographic space it controlled—with behaviors that looked all the world like those of devoted nationalists. Of course, some communists have rejected the entire charade, and like the fidelistas of Cuba, commit themselves to unabashed nationalism with cries like the “Fatherland (Patria) or Death!”

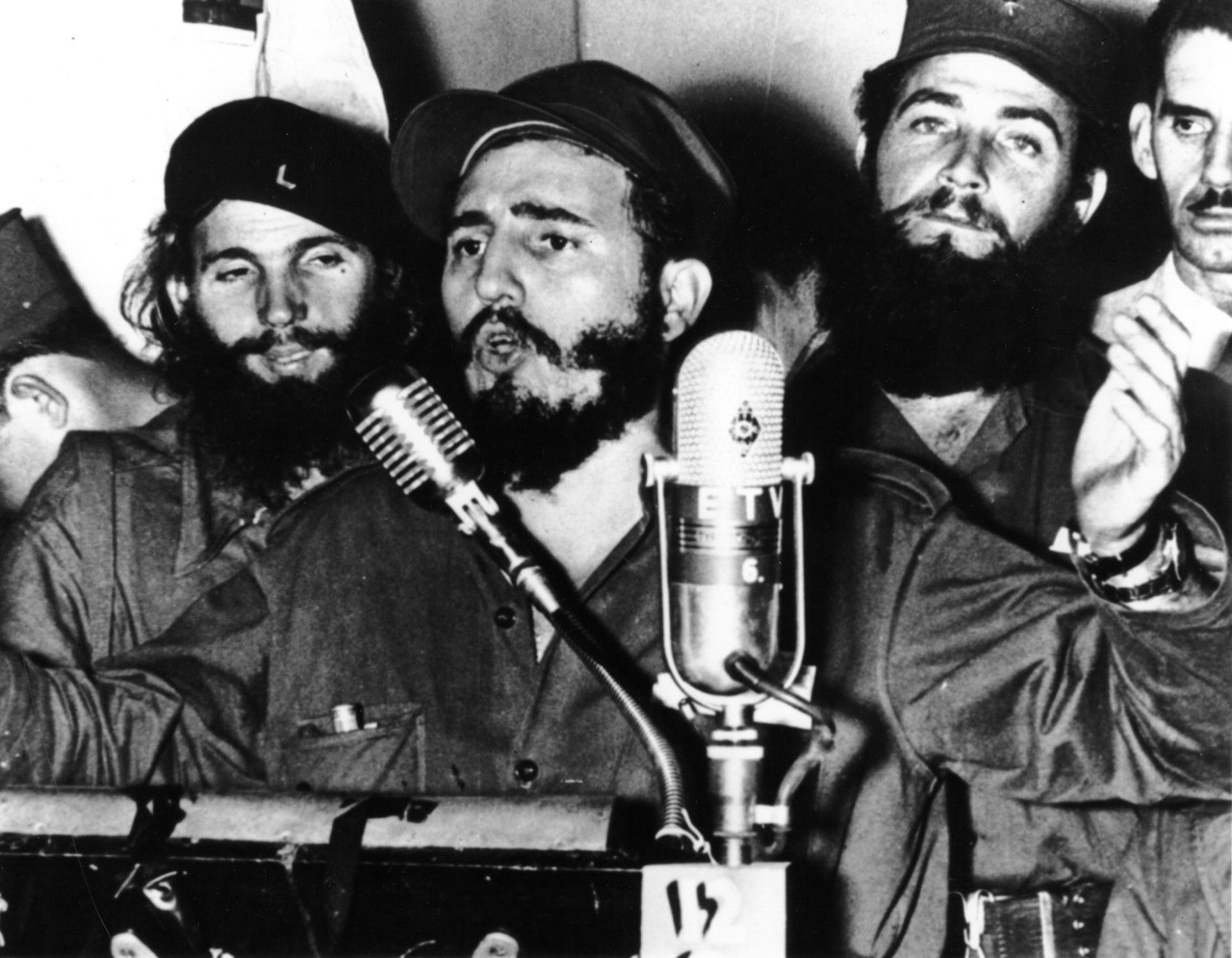

Fidel Castro, surrounded by his Marxist guerrillas, delivers an address in Cuba after assuming power in 1959. (Keystone/Getty Images)

Today, there are few communists and former communists who respect the labored distinction between nationalism and patriotism offered us by the President of France. The distinction no longer serves any political purpose. The Chinese of Xi Jinping do not systematically keep up the pretense. Vladimir Putin is a frank nationalist. One finds nationalism everywhere, with patriotism its overt expression.

The President of France really has very little to teach Americans about nationalism or patriotism. We have among us thousands of young persons who were prepared to expose themselves to mortal danger on the battlefield in order to defend the flag and the values it represents. We do not need instruction from anyone about the true meaning of nationalism and its heroic expression in patriotism.

Professor A. James Gregor is professor emeritus of political science at the University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of thirty academic volumes and is a Knight of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Italy.

Comments are closed.