Pinkerton: Harry Truman’s Campaign Was in 1948, The Truman Show Is Now, The Trump Show Is Coming

New Technology, New Politicians

In politics, every new communications technology creates, or at least empowers, a new style of politician.

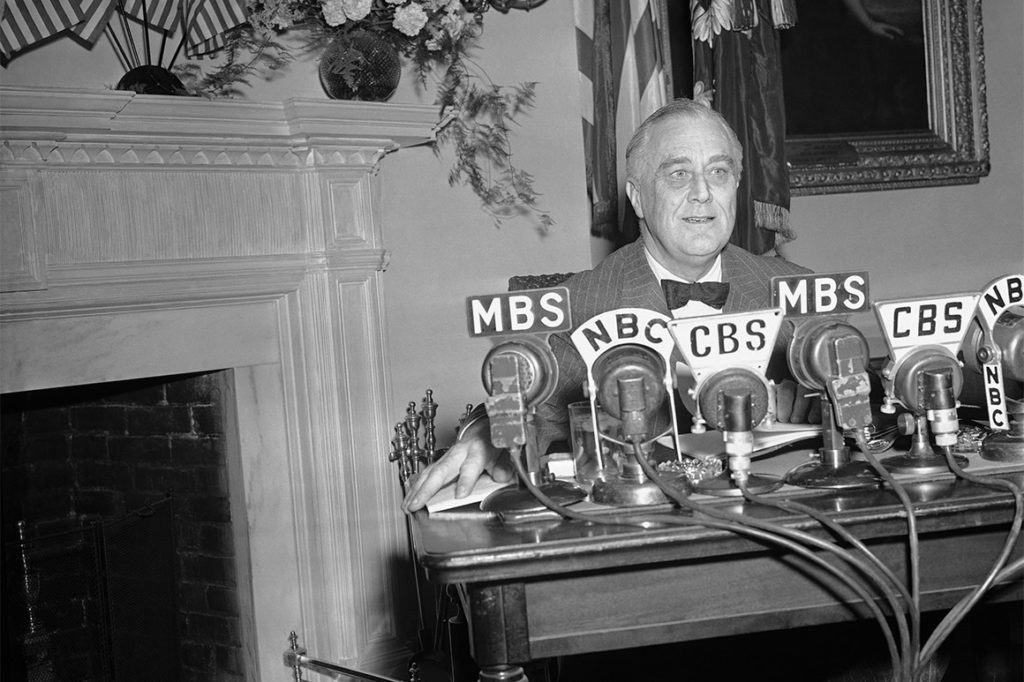

A century ago, electronic amplification enabled political figures to adopt a more relaxed speaking style; they no longer had to yell to be heard in the back row. A little later, radio enabled politicians to become downright conversational, as with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famed “fireside chats” in the 1930s.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt speaks to the nation from in front of a fireplace in the White House on Dec. 9, 1941. | AP Photo

Then came television. John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan, to name two telegenic presidents, showed their mastery of that medium. More recently, within the category of television, we’ve seen the new style associated with “reality TV”; that niche has given us, most consequentially, The Apprentice, the show that introduced Donald Trump to a nationwide audience.

Of course, the biggest technological change has been the Internet, which helped propel Barack Obama into the White House in 2008. Indeed, for a while, it seemed as though the biggest impact of the Net would be the use, and abuse, of Big Data, as we have seen with Facebook.

Yet now we see that the Internet is creating a new kind of media, and thus a new kind of media-shaped politician. In fact, even older politicians are struggling to retool themselves for this newer media environment. So as we look to the 2020 elections, and beyond, it’s worth considering what sort of political figures will be rising to the top. If the past is any guide, those who master the newest media will soon enough be the victors.

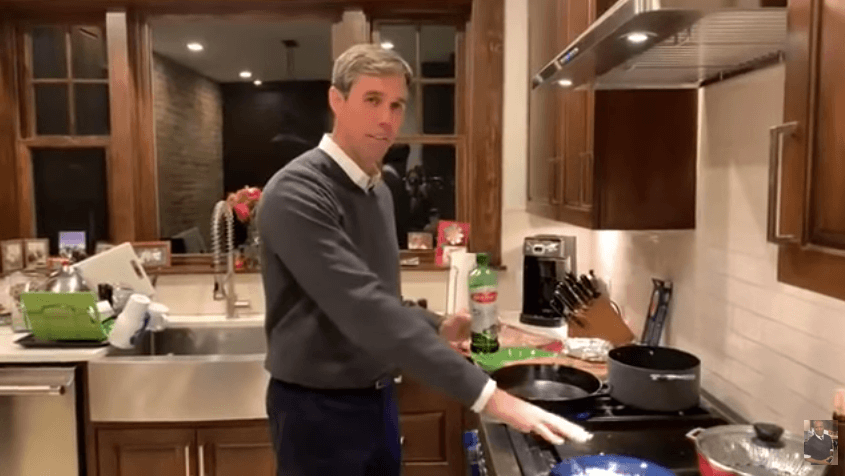

On December 10, The Washington Post offered an interesting headline: “Town hall? 120 people. Live-streamed chicken dinner? 257,000 views on Facebook.” As the article noted, Rep. Beto O’Rourke, who just ran a close-but-losing Senate race against Sen. Ted Cruz in Texas, recently held a town hall in his El Paso district, and 120 people came to hear him. Then O’Rourke went home, cooked dinner with his wife—and 257,000 people watched via Internet streaming. In other words, the Texas Democrat enjoyed more than 2,000 times the audience for his cooking than for his town-hall-ing. Numbers such as these get the attention of politicos, and political consultants, and so they are compelling to anyone interested in politics.

Streaming video enables candidates to create, in effect, a specific brand, and to attach that brand to specific destinations on the web. That is, in setting up events on their social-media pages, politicos can communicate with as many people as might be interested in clicking in to watch them.

If we step back, we can consider how appealing this opportunity must be to candidates. That is, most of the usual concerns about finding a venue are now obviated; the candidate no longer needs to find space in, say, an auditorium. Instead, the venue is now the candidate’s office, or living room, or moving vehicle—or anywhere.

At the same time, the potential audience also has it easier. Folks no longer need to worry about transportation, or babysitters, or much of anything, other than simply clicking. And heck, if the audience misses the live event, the videos, as well as the podcasts, are just sitting there waiting. For a politically minded couch potato, what’s not to like?

To be sure, the potential of digital politics has been evident for a couple of decades now, and yet still, most people have chosen to “consume” politics in more familiar ways. That is, they go to an event, they turn on the TV news, they read about it (although mostly now they read online).

What’s changed in the last year or so is two-fold: First, the candidates are more aware of the value of social media, and especially of streaming; it is, after all, a great way to connect with a lot of people, fast. Second, as the technology—most obviously, the prevalence of broadband—has improved, people find that the online watching experience is far more reliable and satisfying.

So now, in 2018, we’re seeing something interesting: Each candidate is, in effect, creating his or her own “channel.” That is, just about any candidate for high office now boasts homepages on social media, including Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube.

In other words, if a citizen is interested in one particular candidate, chances are that it’s possible to “graze,” every day, on that candidate. And happily, from the grazer’s point of view, there are no commercials—because the whole show is the commercial. (Digital consumers should always remember that the social-media companies are avidly harvesting their data, gleaning information about whatever it is that they’re clicking on.)

We can quickly see that this new relationship reduces the importance of reporters; the two-dollar word for this phenomenon is “disintermediation,” which simply means that a middleman isn’t in the middle anymore. That is, if the candidate and the people can connect directly, then reporters matter less; voters don’t need an intermediary to tell them what they just heard. (There will always be a place for commentary, but it must actually offer added value to the news consumer, and not all commentators are good at adding such value.)

In the meantime, as each politician is increasingly the star of his or her own show, the showrunners must be mindful of the the quality of the show, including its production values. As the Washington Post article detailed, top presidential candidates—that is, those who tend to have the most money, and the most to gain—are increasingly building little studios to help showcase themselves.

Studios, that is, that can travel with them wherever they go. As the Post observed, “Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), are well on their way to creating entirely independent in-house news channels, sometimes traveling the country with professional crews who provide multicamera setups and polished feeds that get stream counts in the hundreds of millions.”

Once again, the key variable is improved technology. Thanks to portable and robust—and, if need be, easily replaceable—equipment, the likes of O’Rourke, Sanders, and Warren can now be “camera ready” just about anywhere.

However, this observer questions whether or not older candidates can truly compete with younger “digital natives.” That is, just as the coming of radio and then television weeded out some non-adaptive candidates, the same will likely hold true for the new social media; it’s a young person’s game.

Please don’t accuse this author of “ageism”! These are just speculations about who’s likely to succeed in a campaign when hundreds of formal events—debates, cattle shows, etc.—are supplemented by millions of new-media “micro-events,” as candidates tweet or stream some passing thought.

In this new-media environment, the 2020 Democratic nomination quest will thus be newly arduous, as dozens of candidates seek to jump new-media hurdles. This new always-on style will be more of a challenge to those who aren’t used to it. Thus the notably energetic O’Rourke, in his 40s, would seem to have a big edge over Sanders and Warren, who will both be in their 70s.

The Trump Show and the Truman Show

Yes, plenty of Republicans, too, are migrating to digital programming—although the Post, for some reason, chose to focus on Democrats.

Meanwhile, President Trump, who always does things his way, gave us a taste of what an updated reality TV-style “Trump Show” might be looking like. On December 11, he hosted Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer in the Oval Office and proceeded to open a debate on a border wall. As an admiring John Nolte of Breitbart News wrote, Trump delivered a “seventeen-minute made-for-TV spectacle.” In other words, Trump is likely to be full of media-savvy surprises in the new two years. And even if it’s impossible to know what he has up his sleeve, as the December 11 moment showed, it could well involve bringing cameras into heretofore cloistered meetings and places.

Indeed, thanks to all this media ubiquity, the life of the candidate is increasingly one long bit of performance art; the camera is always on, and so the candidate, too, must always be on. And of course, given that just about everyone has a cellphone camera nowadays, politicians are well-advised always to be on their best behavior. Yes, political life today is a bit like the scenario of the 1998 movie, The Truman Show; somebody’s camera, or cameras, is always on.

So as we can see: such a life-under-glass puts a premium on the candidate’s ability to be interesting at all times. And if the candidate can’t always be interesting (and who can?), then at least he or she must be disciplined not to say something stupid. In other words, for all the changes we are seeing now, a familiar rule applies: You have to work hard to make it look easy.

Still, all office-holding politicians have one thing in common: they are real. That is, by virtue of their office, they have some sort of official power. And so somebody will always be interested in what they have to say.

In the meantime, the onus is on the campaign staff to help keep the politician’s show as entertaining as possible. After all, if it’s easy for an audience to come, it’s also easy for it to go.

So entertainment-minded campaign aides will thus be in an “arms race” to introduce showbiz-y elements to keep things interesting, such as a guest, a song, a prop, Q and A with the audience, and who knows what else—augmented reality? virtual reality?

In other words, media advisers are increasingly fulfilling functions borrowed from TV and even film—namely, the functions of director, producer, script-writer, special effects coordinator, and stagehand.

So we can see: Campaigns are becoming sort of like reality TV shows, but with a difference: These days, the candidates, not the networks, increasingly control the show.

That is, the candidates no longer need to negotiate with a TV network in order to do an interview. They don’t need to travel to a TV studio to do a “hit” at a scheduled time—or even to accommodate the schedule of a reporter—because they have their own studios, their own distribution networks, and can go live any time they wish. In addition, if the candidates produce their own show, on their own terms, they are a lot more likely to capture the audience-data for the show than they would if they simply went on someone else’s TV channel.

Again, the point here is not that “the media”—however that word is defined these days—are unimportant. Instead, the lesson is that the familiar media are less important. The data-drenched new media are simply more important.

Down in Texas, O’Rourke’s candidacy proved that campaigns can be run like, well, a media start-up. Early on, O’Rourke was regarded as a long shot, and yet soon, his neo-Bobby Kennedy message of dreamy liberalism went viral nationwide. In particular, his vigorous defense of Colin Kaepernick and “taking a knee” received millions of views across many portals. And so O’Rourke raised an astonishing $70 million, mostly from small donors.

Once again, we must note that O’Rourke lost his race. And yet to his fans, he’s a winner. And if he seems to be more of a “national Democrat” than a “Texas Democrat,” well, most Democrats are national. So it’s not surprising that a December 11 online straw poll of the 2020 Democratic hopefuls conducted by Moveon.org found O’Rourke in the lead.

So yeah, a lot of people around the country are interested in what O’Rourke ate for dinner last night. And so even if lightning doesn’t strike for him in ’20, he’ll still be young, not yet 50. So there’ll be plenty of opportunity for the Beto Show to keep building its audience.

Of course, soon enough, every candidate will have the same idea, and so there will be thousands of shows to choose from. Which is to say, if he doesn’t win something soon, Beto could lose his mojo.

That’s a lesson borrowed from The Truman Show: Your daily life might make for a good program, but if things slow down, well, you could be cancelled.

In the meantime, for consumers—oops, I mean voters—it’ll be a kind of spontaneous Netflix for politics. That is, there’ll be bounteous content, just sitting there waiting, for anyone to watch.

Yes, there’ll be more such content than any one individual could possibly watch in a lifetime, and yet still, because of the glut, there’ll always be at least something that’s entertaining.

This is the first of two parts. Next: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez: Social Justice Warrior Meets Social Media Warrior

Comments are closed.