Mansour: Instead of ‘Canceling’ Thanksgiving, Celebrate It as Our Founding Myth

“Let’s be grateful that we can still celebrate Thanksgiving – because I’m sure the left will declare this a hate crime soon.”

I was only half-joking when I said those words at last year’s Thanksgiving dinner. I’m not joking at all now. It’s only a matter of time before they “cancel” Thanksgiving because it’s “founded on racism.”

The Wokesters are hard at work rewriting our history one school kid at a time. Ann Coulter gave an excellent summary of the new interpretation of Thanksgiving: “As every contemporary school child knows, our Pilgrim forefathers took a break from slaughtering Indigenous Peoples to invite them to dinner and infect them with smallpox, before embarking on their mission to fry the planet.”

She’s not joking either. America’s teachers have “begun a slow, complex process of ‘unlearning’ the widely accepted American narrative of Thanksgiving,” Education Week reports. To unlearn the “myth” of Thanksgiving, educators are seeking ways “to help students appreciate colonial oppression of Natives and the violence that ensued from it.” The article helpfully includes a video of PBS NewsHours’ Judy Woodruff explaining that the “quintessential feel-good holiday” of Thanksgiving actually “perpetuates a myth and dishonors Native Americans.”

The story of Thanksgiving fares even worse on college campuses, where students are taught that it should be commemorated as a “National Day of Mourning,” not a day off for food, family, and football.

“It’s kind of just based off the genocide of the indigenous people,” one student at Minnesota’s Macalester College told the College Fix. “The history of the holiday is obviously not the best. It’s very violent and oppressive,” said another.

Like the Democrats’ impeachment narrative, this new “narrative of Thanksgiving” is total bulls**t. I know because I’ve read the transcript.

Our knowledge of the Pilgrims comes from two primary sources. The earliest account is from Edward Winslow, whose report on the earliest days of the Plymouth settlement was published in London in 1622, just two years after the Pilgrims landed in the New World. The more detailed and authoritative account comes from the Pilgrims’ second governor, William Bradford, whose poignant and eloquent history Of Plymouth Plantation, written between 1630 and 1651, tells the story of the community from their formation in England to their exile in Holland and their eventual founding of the Plymouth Colony.

Any fair reading of the primary source documentation will give you all the evidence you need to understand why we chose to make the Pilgrims the center of our founding myth.

But before I examine that record, let me make clear what I mean by “founding myth.” I’m using that term in the way that the Greeks and Romans understood it. A nation’s origin myth isn’t a falsification of history meant to deceive. Quite the contrary! It is a story rooted in history that reflects a nation’s most sacred values, rituals, and identity.

Take, for example, the Aeneid, Virgil’s epic poem recounting the founding myth of ancient Rome. In one of the most memorable passages, Virgil provides us with a perfect reflection of the Roman concept of pietas, which means a religious and familial duty. Virgil describes his hero, Aeneas, fleeing the burning city of Troy while grasping the hand of his young son and carrying on his back his elderly father who is cradling in his arms their family’s household gods. In that beautiful tableau Aeneas reflects all the values the Romans held most sacred; he is honoring and protecting his family and his gods, as he flees the fall of one civilization and courageously sets out to found another, greater one in Rome.

There is a reason why we chose the Pilgrims and their establishment of the Plymouth Colony in 1620 as our founding myth, not the Virginians who settled in Jamestown over a decade before that date. Our reasoning had everything to do with the Pilgrims’ lack of racism.

The story of the Pilgrims embodies our most sacred American values. Like Aeneas fleeing the fall of Troy, the Pilgrims saw themselves as fleeing a cataclysmic conflagration about to engulf Europe. And like the Roman hero, they too hoped to build a new civilization with a spark from the dying embers of the old one.

They were devout Christians, and much like evangelical Christians today, these Englishmen and women sought to live by a simpler Biblical-based faith modeled after the early church of the Apostles. They wanted to live as a community that worshipped and worked together, but England and its established Church enacted laws that forbade religious gatherings in private houses. These laws basically thwarted their ability to practice their faith as a community. So, in 1608, faced with the threat of imprisonment for their faith, the small community fled England and settled in Holland, which was known as a refuge for Protestant dissenters.

But after living a decade among the Dutch, these English Christians realized it was time to leave the Old World altogether. In 1618, Europe was on the cusp of one of the most violent periods in its history. The conflict, which became known as the Thirty Years War, would pit Protestant and Catholic European powers against each other. For the Pilgrims, the impending cataclysm seemed like the beginning of Armageddon. They felt the best course of action was to leave the Old World behind and try to establish some holy remnant in the new one.

Getting there was the hard part. The small community was not wealthy. They were working class folks. But the congregation pooled their resources and obtained a land patent from the Plymouth Company to settle in an area at the northernmost tip of the Virginia Company’s colony. They would eventually receive financing from London bankers who offered to back their venture with the understanding that the Pilgrims would repay these debts with their labors in the New World.

A merchant vessel called the Mayflower was charted for them, but the London financiers made it clear that the Pilgrims weren’t going to be the only passengers. The investors insisted that a rag tag crew of non-religious settlers—who the Pilgrims referred to as “the Strangers”—were also coming along for the ride, and that would soon become a source of awkwardness. But that was the least of their worries, really.

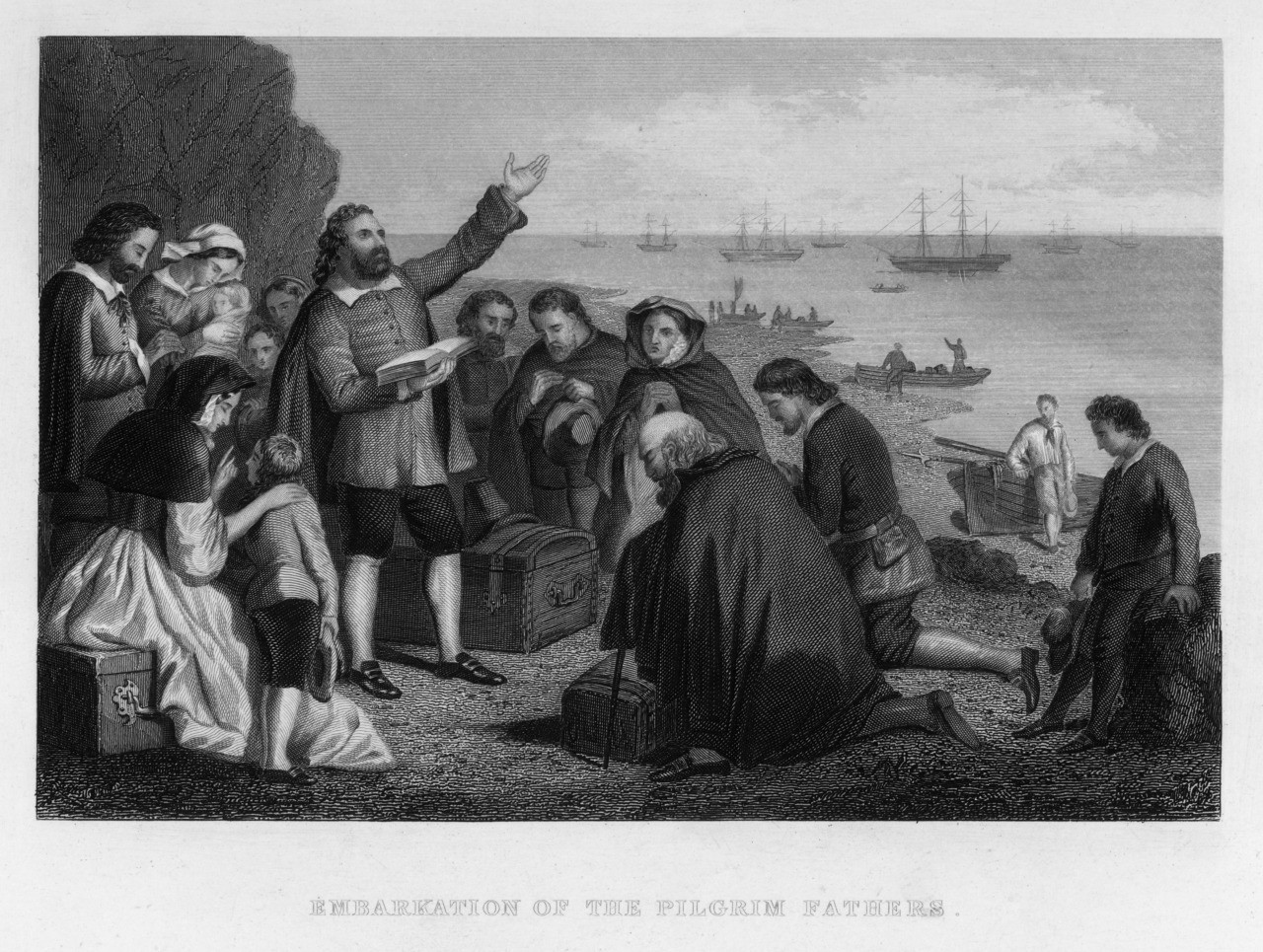

The ‘Embarkation of the Pilgrim Fathers’ from England in September 1620, as they commence their journey on the Mayflower to the New World. (Archive Photos/Getty Images)

By the time they left Plymouth, England, on September 6, 1620, they were setting sail way too late in the year for a successful journey. Trans-Atlantic sea voyages were still a frightening and challenging endeavor. It was comparable to going to the Moon. Even the best crossing was perilous, and that would be in springtime when the weather was more moderate. To set out in September meant they were arriving in winter … But wait, it got worse…

After 65 days—and two deaths—at sea, the Mayflower made landfall on November 9, 1620.

“Having found a good haven and being brought safely in sight of land, they fell upon their knees and blessed the God of Heaven who had brought them over the vast and furious ocean, and delivered them from all the perils and miseries of it, again to set their feet upon the firm and stable earth, their proper element,” Bradford wrote of that moment.

But the jubilation was short lived. They soon discovered that they were over 200 miles off-course. They were nowhere near Virginia! And it was almost winter—in Massachusetts!

“Having thus passed the vast ocean, and that sea of troubles,” the Pilgrims “had no friends to welcome them, nor inns to entertain and refresh their weather-beaten bodies, nor houses — much less towns — to repair to,” Bradford wrote:

As for the season, it was winter, and those who have experienced the winters of the country know them to be sharp and severe, and subject to fierce storms, when it is dangerous to travel to known places, — much more to search an unknown coast. Besides, what could they see but a desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts and wild men; and what multitude there might be of them they knew not!

…Summer being done, all things turned upon them a weather-beaten face; and the whole country, full of woods and thickets, presented a wild and savage view.

“So, why didn’t they just turn around and head south for Virginia?” you ask. Because the Mayflower Captain told them that he couldn’t spare any more provisions. He needed to keep stores saved for his own return voyage. So, they had to shove off and muddle onshore as best they could because he wasn’t hanging around forever, and if they didn’t get a-move on he might just dump them onshore and abandon them before they even had time to build a shelter.

Again, Bradford, writing in third person, explained the situation the Pilgrims found themselves in:

If they looked behind them, there was the mighty ocean which they had passed, and was now a gulf separating them from all civilized parts of the world. If it be said that they had their ship to turn to, it is true; but what did they hear daily from the captain and crew? That they should quickly look out for a place with their shallop, where they would be not far off; for the season was such that the captain would not approach nearer to the shore till a harbour had been discovered which he could enter safely; and that the food was being consumed apace, but he must and would keep sufficient for the return voyage. It was even muttered by some of the crew that if they did not find a place in time, they would turn them and their goods ashore and leave them.

And then a new conflict arose before they could even get started. They had no governing agreement binding them. Their charter was for Virginia, not wherever this place was.

The “Strangers”—who weren’t especially civil or pious—felt no allegiance to the Pilgrims or each other. They figured it was every man for himself. But with winter setting in and with dangerously few provisions to speak of, the Pilgrims knew that if they didn’t all stick together, they would all die.

Edward Winslow explained what happened next:

This day before we came to harbor, observing some not well affected to unity and concord, but gave some appearance of faction, it was thought good there should be an association and agreement that we should combine together in one body, and to submit to such government and governors as we should by common consent agree to make and choose, and set our hands to this that follows word for word.

And, thus, they wrote out and signed what became known as the Mayflower Compact, the first governing document of the Plymouth Colony—and the first document to establish self-governance in the New World.

Here are the words:

IN THE NAME OF GOD, AMEN. We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, &c. Having undertaken for the Glory of God, and Advancement of the Christian Faith, and the Honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the first Colony in the northern Parts of Virginia; Do by these Presents, solemnly and mutually, in the Presence of God and one another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation, and Furtherance of the Ends aforesaid: And by Virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony; unto which we promise all due Submission and Obedience. IN WITNESS whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cape-Cod the eleventh of November, in the Reign of our Sovereign Lord King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth, Anno Domini; 1620

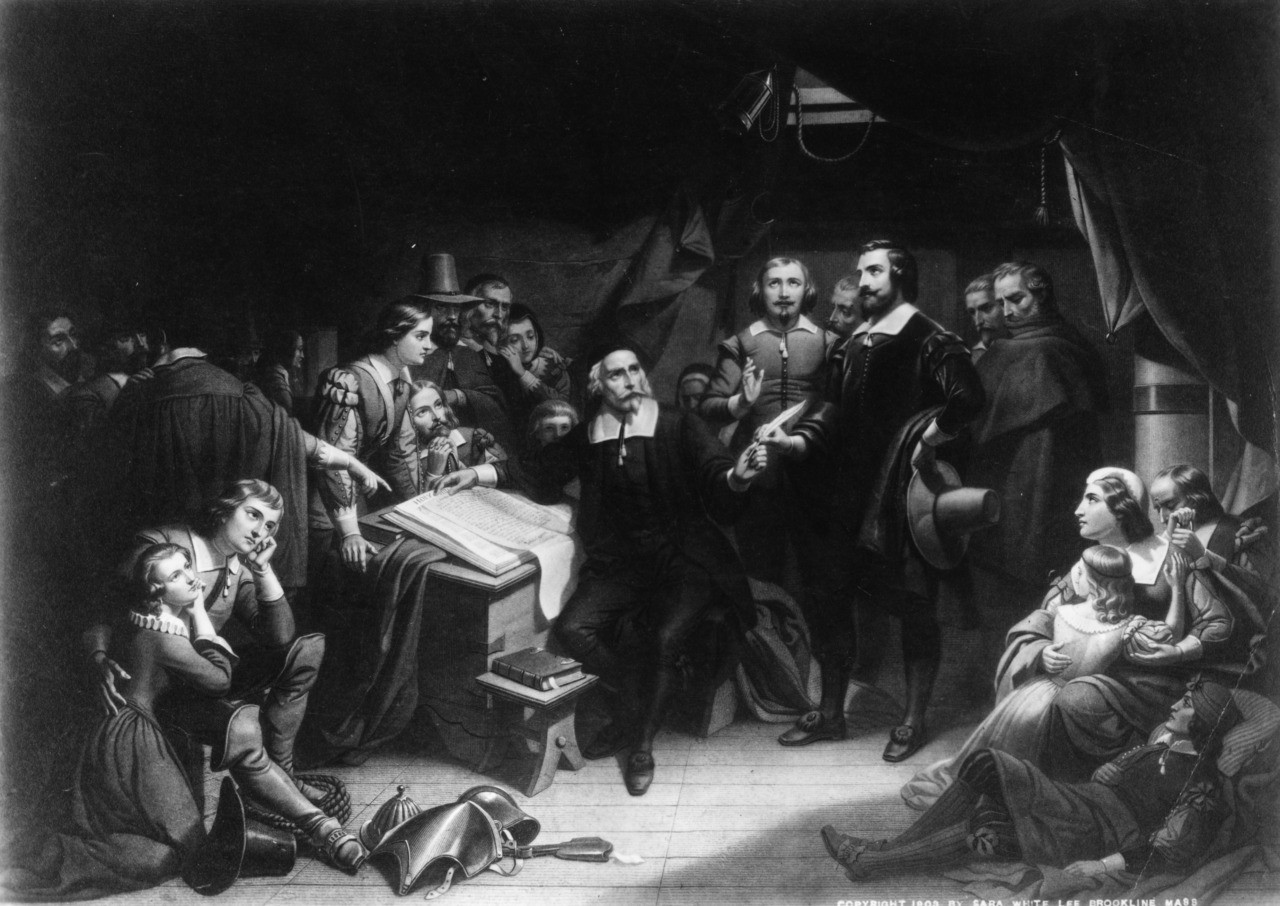

1620, Pilgrim leader William Bradford reading the Mayflower Compact on board the Mayflower off the coast of what became known as Massachusetts. Signed by all the adult males on board, the compact bound all the passengers together. (MPI/Getty Images)

It was clear to all of them that the only thing binding them to this governing document was their own consent as the ones being governed by it.

“What they did was enact social compact theory that had been sort of kicked around in Europe, especially in Britain, for a while,” University of Oklahoma historian and author Professor Wilfred McClay told Breitbart News Tonight. “They created a body politic out of the consent of those who were aboard the ship, and they had the foresight to realize they should and could do that.”

The Mayflower Compact wasn’t an elaborate political and legal charter establishing a system of government, like our Constitution. Nor was it a treatise establishing a governing philosophy, like our Declaration of Independence. It was little more than a paragraph. But within that paragraph we have the kernel of our democracy.

This true historical event, taking place nearly two centuries before the signing of the Declaration of Independence, embodied a fundamental American value: the belief that government is based on the consent of the governed.

Having signed a governing agreement, the Plymouth settlers then elected their first governor, John Carver. During their first forays ashore, the settlers discovered that the area was largely desolate. In the years prior to their arrival, the population of the local tribes had been decimated by plague brought by European fisherman and by civil wars with other hostile tribes. The disease had wiped out whole villages, where the settlers found only scattered bones, left to the elements because there was no one survived to bury them.

They decided to build their settlement on the ruins of an abandoned Indian village called Patuxet.

So, finally by December 1620, with the Mayflower anchored a mile offshore, the Pilgrims came ashore in the bitter cold, with rain and sleet pouring down on them, to build their settlement.

Is it any wonder that they lost over half their numbers that winter?

They were ill-equipped. The weather was impossible. Many of them didn’t even leave the Mayflower, and eventually the ship was turned into a makeshift hospital for the sick and dying. Those who settled in the village lived in constant fear of being attacked by hostile Indian tribes. During the course of the winter months, so many members of the Plymouth Colony died that they were afraid to bury their dead lest the Indians realize how thinned out their numbers had become. At one point, Winslow wrote that they propped up the corpses against the trees surrounding the settlement and placed muskets in their arms to disguise the dead to look like sentries guarding the perimeter of the colony.

By the time March came around, the settlers were still barely holding on, but the captain and crew of the Mayflower were ready to leave for the return voyage back to England. It was a make or break moment for the Plymouth Colony. Would they survive on their own with their last tie to England gone and no hope of return?

At that providential moment, an Indian named Samoset of the Wampanoag Tribe walked into the Plymouth camp and greeted them in English, which he had learned from interacting with various contingents from the Virginia Colony.

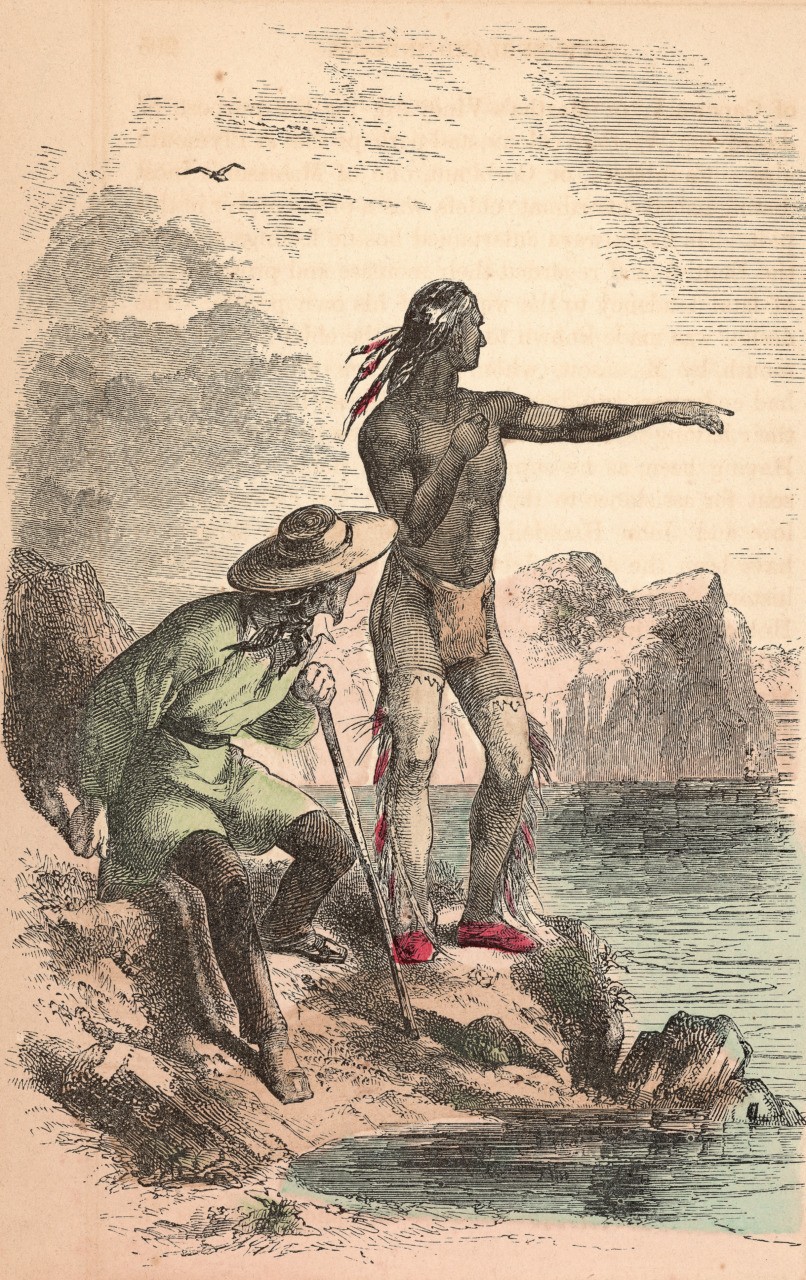

Samoset of the Wampanoag Tribe entered the Plymouth settlement and called out a greeting of ‘Welcome’ in English. The next day brought Squanto, also fluent in English (Archive Photos/Getty Images)

The settlers learned from Samoset that this area was the Wampanoag Tribe’s territory, but the tribe had been so weakened by the plague that their leader, Massasoit, felt increasingly at the mercy of enemy tribes, who also happened to be the same ones menacing the Pilgrims.

As Winslow recounted:

[Samoset] discoursed of the whole country, and of every province, and of their sagamores, and their number of men, and strength. The wind being to rise a little, we cast a horseman’s coat about him, for he was stark naked, only a leather about his waist, with a fringe about a span long, or little more; he had a bow and two arrows, the one headed, and the other unheaded. He was a tall straight man, the hair of his head black, long behind, only short before, none on his face at all; he asked some beer, but we gave him strong water and biscuit, and butter, and cheese, and pudding, and a piece of mallard, all which he liked well, and had been acquainted with such amongst the English. He told us the place where we now live is called Patuxet, and that about four years ago all the inhabitants died of an extraordinary plague, and there is neither man, woman, nor child remaining, as indeed we have found none, so as there is none to hinder our possession, or to lay claim unto it.

Six days later, Samoset returned to the village with the Wampanoag leader Massasoit. After entertaining their visitors with food and sport, the Pilgrims and the Wampanoags negotiated a mutually beneficial agreement. They would defend each other in the event of an attack by the hostile tribes. And later on, they would establish trade with each other. To help the settlers survive the next winter, an Indian by the name of Tisquantum, or Squanto, stayed with the settlers to show them how to plant their spring crops.

Circa 1621, Massasoit, chief of the Wampanoag of Massachusetts and Rhode Island, pays a friendly visit to the Pilgrims’ camp at Plymouth Colony with his warriors. After signing the earliest recorded treaty in New England with Governor John Carver. (MPI/Getty Images)

Squanto’s story offers us a good opportunity to explain the difference between the Plymouth and Virginia colonies.

Squanto spoke English because in 1614, six years before the Pilgrims arrived, an expedition from the Virginia Colony led by Captain John Smith (of Pocahontas fame) charted the area around Cape Cod and Massachusetts Bay.

One of the Virginian commanders with Smith, a man named Thomas Hunt, decided to make extra money by kidnapping Indians and selling them into slavery. Squanto was among the victims Hunt trafficked to England, which is how Squanto learned English. The tragic irony is that, had he not been taken against his will across the ocean, Squanto would have died with the rest of his village when Patuxet was wiped out by the plague. You see, Squanto was the sole survivor of the Patuxets—the people whose deserted village the Pilgrims built their settlement upon.

And yet this man, who had so many reasons to curse the English, was worked side by side with the Pilgrims that spring of 1621, showing them how to plant crops and assisting them in establishing trade with the surrounding tribes.

From their encounters with Squanto and the other Indians, the men and women of Plymouth came to respect the Native people and feel shame for the treatment they endured at the hands of other Englishmen of the Virginia Colony.

Historian Nathaniel Philbrick explains one encounter:

At Cummaquid they encountered disturbing evidence that all was not forgotten on Cape Cod when it came to past English injustices in the region. An ancient woman, whom they judged to be a hundred years old, made a point of seeking out the Pilgrims “because she never saw English.” As soon as she set eyes on them, she burst into tears, “weeping and crying excessively.” They learned that three of her sons had been captured seven years before by Thomas Hunt, and she still mourned their loss. “We told them we were sorry that any Englishman should give them that offense,” Winslow wrote, “that Hunt was a bad man, and that all the English that heard of it condemned him for the same.”

In fact, even before hearing these tales, the Pilgrims were distrustful of the attitude of the other English settlers.

Before they left England, the Pilgrims were looking for a military commander for their settlement. By far the most qualified man for the job was Captain John Smith (again, of Pocahontas fame). No one knew the whole region better than Smith. He literally drew the map of it. But the Pilgrims didn’t like him. They found him arrogant and too worldly and figured they could just make do with his maps without hiring the map-maker.

The dislike was mutual; Smith despised the Pilgrim’s piety and later mocked their refusal to hire him. He would dismissively describe them as “humorists,” meaning fanatics, and would write that the Pilgrims refused “to have any knowledge by any but themselves, pretending only religion their governor and frugality their counsel.” And he meant that as an insult!

Smith was right that the Pilgrims could have saved themselves a lot of grief if they had hired someone who knew where he was going. But in end, the Pilgrims survived thanks to their fortitude, the grace of God and the help of their new friends.

Squanto (aka Tisquantum), from the Patuxet tribe, pointing on a coastal rock while serving as guide an interpreter for Pilgrims. (Kean Collection/Getty Images)

And they were seen as friends. As Winslow would recounted that year, “We have found the Indians very faithful in their covenant of peace with us; very loving and ready to pleasure us; we often go to them, and they come to us.”

Far from being judgmental or superior to them, the Pilgrim Winslow described their Native allies as “a people without any religion or knowledge of God, yet very trusty, quick of apprehension, ripe-witted, just.”

And that brings us to the Thanksgiving story.

With the help of Squanto, the Pilgrims had a successful harvest in the fall of 1621. They had come through the first winter, after losing 60 percent of their group. But rather than mourning the 60 percent lost, they rejoiced that 40 percent still lived and gave thanks to God.

Bradford wrote:

They began now to gather in the small harvest they had, and to fit up their houses and dwellings against winter, being all well recovered in health and strength and had all things in good plenty. For as some were thus employed in affairs abroad, others were exercised in fishing, about cod and bass and other fish, of which they took good store, of which every family had their portion. All the summer there was no want; and now began to come in store of fowl, as winter approached, of which this place did abound when they came first (but afterward decreased by degrees). And besides waterfowl there was great store of wild turkeys, of which they took many, besides venison, etc. Besides, they had about a peck of meal a week to a person, or now since harvest, Indian corn to that proportion.

The famous Thanksgiving harvest feast that we’ve come to cherish is from Winslow:

Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after have a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors; they four in one day killed as much fowl, as with a little help beside, served the company almost a week, at which time amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest King Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain, and others. And although it be not always so plentiful as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.

And there you have it! The Pilgrims gathered for a harvest feast, and the Wampanoags joined them and brought venison to add to feast, which lasted for three days and included sports games (no word on whether it was football!).

Let the record show that this first Thanksgiving actually was a “quintessentially feel-good holiday”!

So why did Abraham Lincoln choose to make this account of Thanksgiving a national holiday in 1863?

Our origin myth was still a matter of some debate up until that time. Throughout the early nineteenth century, Americans hotly debated whether the nation’s founding should be celebrated as the Jamestown Colony in Virginia or the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts. The decision to favor Plymouth was helped along by the rediscovery of Bradford’s beautiful diary, Of Plymouth Plantation.

Bradford’s manuscript had disappeared from the New World in 1777 when the last royal governor of the colony took it from the Old South Church in Boston and carted it across the Atlantic to England. He probably meant it as a final diss to the patriotic New Englanders who were despised by the British as traitors and brigands fomenting rebellion.

For nearly a century Bradford’s manuscript was lost to Americans, until one Boston scholar happened to see a passage in another book quoting Bradford’s journal. He eventually discovered that the manuscript had been housed all that time in the library of the Bishop of London. (Yes, I know, the irony! The Pilgrim Bradford’s journal was being held by a bishop of the very Church Bradford’s community fled England because of!)

For decades, the Brits refused to return the manuscript to its proper owners in the United States. They really know how to hold a grudge.

But at least in 1856 the Brits allowed a special edition of Bradford’s manuscript to be published, and that set off a renewed interest and appreciation for the Pilgrims and their history.

And it came right at a time when our nation was on the cusp of a great conflagration—as bloody and catastrophic for us as the war that caused the Pilgrims to flee Europe. It was a fight over our most basic and sacred values: the right of all men—not just Englishmen—to live in freedom and enjoy fruits of self-governance.

So, is it any wonder that in the midst of the bloodiest year of our Civil War—just one month before he delivered his Gettysburg Address—that Abraham Lincoln decided once and for all that our nation’s founding should harken Plymouth, not Virginia?

Of course, Lincoln chose to honor the ancestors of the New England abolitionists, not the rebellious slaveowners of Virginia.

On October 3, 1863, our 16th president declared that Thanksgiving would be commemorated as a national holiday every year on the last week in November in honor of the Pilgrim fathers.

We choose the Pilgrims as our founding myth because they embodied our most cherished ideals. They were the best of us.

They endured despite the odds, and through trial and error established the practices of self-governance, private property, a common defense, and peaceful commerce as a means to co-exist. They even established a sense of religious tolerance and pluralism with the “Strangers” among them, who also became friends.

To celebrate their story is not to denigrate the pain felt by our Native communities or to dismiss the bad behavior that followed. On Thanksgiving we acknowledge that the Pilgrims and the Natives did, in fact, come together in peace that November 1621, and that is the example we aspire to.

We celebrate their story to acknowledge our highest aspirations, not to whitewash our history or to minimize our mistakes. Thanksgiving affirms who we want to be because it is about who the Pilgrims actually were.

“There is a kind of audacity about these people,” Professor McClay told me this week on Breitbart News Tonight. “The journeys were dangerous. The habitats into which they were coming were brutal. They lost many lines and yet they had this sense—and [the Puritan leader John] Winthrop says it in his sermon—that they were on a mission from God, ‘That the eyes of all people are upon us’—which, when you think about it, this is like somebody going to the Moon—the dark side of the Moon—and saying, ‘The eyes of all people are upon us.’ Well, actually you’re on the moon. Nobody’s watching! And yet they were so deeply committed to the vision of what they were doing, and that was the germ of what became ultimately a great nation.”

Actually, they knew that God was watching.

In Of Plymouth Plantation, Bradford described the fateful moment when the Pilgrims realized that they had landed in an unsettled area, and there was no way to turn back:

What, then, could now sustain them but the spirit of God, and His grace? Ought not the children of their fathers rightly to say: Our fathers were Englishmen who came over the great ocean, and were ready to perish in this wilderness; but they cried unto the Lord, and He heard their voice, and looked on their adversity.

… Let them therefore praise the Lord, because He is good, and His mercies endure forever. Yea, let them that have been redeemed of the Lord, show how He hath delivered them from the hand of the oppressor. When they wandered forth into the desert-wilderness, out of the way, and found no city to dwell in, both hungry and thirsty, their soul was overwhelmed in them. Let them confess before the Lord His loving kindness, and His wonderful works before the sons of men!

Amen. And Happy Thanksgiving.

Comments are closed.