Pinkerton: October Surprises in U.S. History

Another October Surprise

So now we have our “October Surprise”—at least one of them. The news that President Trump has tested positive for Covid-19, has been hospitalized, and released, throws the remaining weeks of the presidential campaign into an even more uncertain kind of uncertainty. In the next few days, and for the rest of the campaign season, it’s a cinch that every possible rumor—about his health, about presidential politics, and about everything else—will be thrown around. And the only way to beat down false rumors is with the truth, delivered as transparently as possible.

For instance, one way not to handle the illness of a commander-in-chief is the way that President Woodrow Wilson handled his illness in October 1919. On October 2 of this year, historian Michael Beschloss tweeted the front page of the New York Times from more than a century ago, on October 3, 1919; the banner headline read, “Doctors In Consultation Call Wilson ‘A Very Sick Man.’”

President Woodrow Wilson was afflicted by a massive stroke at the White House 101 years ago today: pic.twitter.com/p7jCZVTOSx

— Michael Beschloss (@BeschlossDC) October 2, 2020

In a follow-up tweet, Beschloss added, “After his massive stroke 101 years ago . . . Woodrow Wilson showed wrong way to deal with Presidential illness—concealed almost everything about his condition, ignored VP and Cabinet (and was furious when they met in his absence), let wife make important decisions in his stead.”

Yes, Wilson and his inner circle handled the matter badly; fortunately for the nation, the 28th president was not on the ballot in the next presidential election year, 1920.

The Best-Known October Surprise Was No Surprise

Interestingly, the most famous “October Surprise”—and the period in history that gave rise to the phrase—is the one that never happened. Back in 1980, the meme of “October Surprise” referred to the rumor that President Jimmy Carter had a sneaky plan up his sleeve, aiming to gain the release of the Americans held hostage in Iran just prior to the presidential election. The presumption, of course, was that a sudden jolt of good news would boost Carter’s bid for a second term.

The American hostages had been seized by the Iranians in November 1979, and their plight became a major issue throughout the 1980 election year. Yet as it happened, Carter had no such sneaky or surprising plan. He would have loved to get the hostages out at any time, obviously, but there was no special arrangement to release them prior to November 4, 1980. And on that day, with the hostages still in Iranian captivity, Carter lost in a landslide to Ronald Reagan. The Americans were finally released in January 1981.

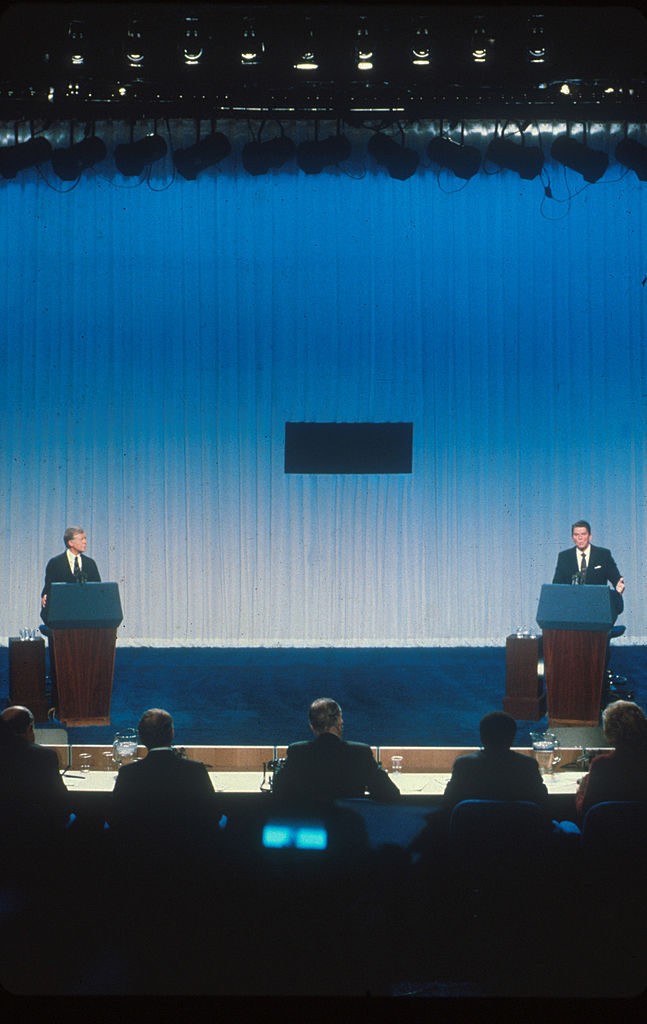

In fact, the biggest surprise of October 1980, at least in terms of presidential politics, came in the single debate held between Carter and Reagan, which occurred in Cleveland on October 28. Reagan did surprisingly well, and so what had seemed to be a close election turned into a landslide; the Gipper won by ten points, carrying 44 states. (So yes, today, we might mull the seeming likelihood that there will be only one debate in 2020, not three, and that the one debate this year was held in . . . Cleveland.)

Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan debate each other from separate podiums October 31, 1980, prior to the 1980 presidential election. (Photo by Liaison via AP)

Yet there’s a curious coda to the 1980 October Non-Surprise. In 1991, former Carter national security aide Gary Sick published a book, October Surprise: America’s Hostages in Iran and the Election of Ronald Reagan, arguing that it was the Reagan campaign that had conspired with the Iranians to prevent the hostages from coming home prior to the election. That is, Sick was asserting that the Reaganites had planned their own kind of October Surprise, as a dirty trick on Carter—and on America. Sick’s book received enormous attention at the time, even if little or nothing of his allegation stood up to scrutiny.

Thus the Sick book serves as a reminder that those who have influence with the media and the liberal establishment can oftentimes plant an idea that has no factual foundation. So in the hands of a crafty liberal, the rumor that Carter was planning to pull one over on Reagan became the printed and published allegation that Reagan was the perpetrator, and Carter was the victim.

Other October Surprises

So now, if we look back into presidential-election history, we can see other October Surprises of various kinds.

For instance, in 1956, we saw two October Surprises. The first was the Hungarian Revolution, erupting on October 23, in which freedom fighters took to the streets of Budapest, as well as of other cities, seeking to overthrow Soviet domination of their country.

In the meantime, here at home, the incumbent U.S. president, Dwight Eisenhower, then running for a second term, stopped short of active intervention in Hungary, but helped facilitate the escape of some 200,000 Hungarians from communist tyranny.

The second surprise was the Suez Crisis, beginning on October 29, in which Britain, France, and Israel went to war against Egypt. The fighting was something of a misfire, and soon ended, and yet for at least a time, it seemed possible that it could escalate into a U.S.-Soviet confrontation. Once again, Eisenhower played a constructive role in bringing the hostilities to a close.

Ike was innocent of any sort of manipulation in either incident, and yet nevertheless, he benefited politically; his sturdy image of peaceful resolve in the midst of foreign turmoil helped him to win a reelection that November by a 15-point margin, carrying 41 of 48 states.

Then, in 1972, there came another October Surprise. On October 26, just 12 days before the national election, President Richard Nixon’s top diplomat, Henry Kissinger, declared, “Peace is at hand.” Kissinger was referring to a breakthrough in the arduous negotiations he had been conducting with the North Vietnamese for the past three years—later including the Russians and the Chinese—seeking an end to the Vietnam War.

In this October 26, 1972, file photo, then presidential adviser Henry Kissinger tells a White House news conference that “peace is at hand” in Vietnam. (AP Photo)

Critics accused Kissinger of manipulating the timing of the good news for the benefit of Nixon’s reelection, and yet in point of fact, the war had already been drawing to a close, thanks to Nixon’s leadership. Having inherited a war from his presidential predecessor, Lyndon Johnson, in which more than 500,000 American troops were fighting in Southeast Asia, Nixon had, by October 1972, reduced the number of troops to around 20,000.

In fact, the final peace agreement was signed in January 1973; for his efforts, Kissinger was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

A generation later, on October 12, 2000, the destroyer USS Cole, anchored in Yemen’s Aden harbor, was attacked by suicide bombers in a small boat. Seventeen sailors were killed, and 39 injured; the perpetrators were a part of Osama bin Laden’s then-obscure al-Qaeda organization. It’s hard to pinpoint just how much impact this attack had on the presidential election the following month, and yet some observers believed that it contributed to the perception that President Bill Clinton hadn’t been taking terrorism seriously enough. As we know, Clinton’s vice president, Al Gore, lost the 2000 election, by a narrow margin, to George W. Bush.

A small boat guards the USS Cole in Aden, Yemen, October 20, 2000. Investigators have found bomb-making equipment in an apartment near the Yemeni port and believe two former occupants may have carried out the suicide bombing that killed 17 sailors aboard the USS Cole. (AP Photo/Hasan Jamali)

It can be argued that Bush, too, failed to take al-Qaeda seriously enough—and that’s why we were taken by surprise on September 11, 2001.

Then, in October 2016, came another pair of October Surprises. On the 7th came the news of Donald Trump’s Access Hollywood tape, which temporarily threw his presidential campaign into a tailspin. And on the 28th came the news that FBI Director James Comey was investigating Hillary Clinton’s e-mails, throwing her campaign into a tailspin.

So as we can see, events can take fateful turns on the eve of a presidential election. Of course, such drastic turns can, and do, happen at any time, and yet now, in October 2020, as so many eyes are glued to political events, we realize how much effect they can have.

And we should keep in mind that the month of October has only just begun.

Comments are closed.