Missed delivery: Why does Amazon, the company that sells nearly everything, nearly everywhere, do next to no business in Russia?

Its brown packages and speedy delivery make Amazon the most recognizable shopping service from Toronto to Tokyo but, while the company is taking on TV and trialing drone delivery, it has yet to crack the world’s largest country.

On paper, Russia is a colossal opportunity for the US retailer. With a population of 145 million people, estimates suggest the nation has more domestic internet users than Amazon’s second-largest market, Germany. On Thursday, a new report showed that last year saw explosive growth in the e-commerce market, with $37 billion changing hands online.

However, while the Seattle-based firm has mooted an entry into the Russian market for more than a decade, it has yet to actually launch a proper local offering. It doesn’t even appear in the rankings of the most popular e-commerce sites, and its business in the country generally just ships in foreign-made products to consumers willing to pay the hefty tax and shipping charges.

The retail giant’s founder, Jeff Bezos, the world’s second richest man, has previously set out his ambitions “to sell everything” to virtually everyone. His firm already operates dedicated marketplaces in 14 of the world’s 20 largest economies, as well as doing substantial trade exporting to smaller states. However, from Moscow to Murmansk, from Kaliningrad in Central Europe to Khabarovsk in Far East Asia, Russia remains a black hole for the company, despite having the world’s sixth largest GDP, adjusted for purchasing power.

While this appears to be a surprising state of affairs given Amazon’s otherwise colossal global reach, the decision-making at play has been poorly characterized by analysts. Digital Commerce 360, an expert trade-industry publication, listed the country among six tough nuts for the business to crack, effectively writing off the prospects it would ever break through. The reasoning, its analysts said, was that Russia is an “authoritarian, nationalist regime,” and that “tensions with the US pose problems.”

China, a one-party state, and Saudi Arabia, a literal despotic kingdom, were described in less dramatic political terms, with talk of local competition and mergers and acquisitions seen to be the key challenges in those markets. On top of that, the analysis falls short when the scale of other American businesses operating in Russia is considered. McDonalds, once seen as the beacon of Western capitalism during the Soviet era, saw its share price soar when it announced it would break ground on its “800th branch” in the country before the end of last year.

Along with fellow US chains like Burger King and KFC, the golden arches have cornered the fast-food market despite the apparently irreconcilable political differences between Moscow and Washington. Coca-Cola, Starbucks, Nike and Google are also among those American firms that do a roaring trade in Russia.

So if foreign giants can make money in the country, why can’t Amazon? For one thing, Amazon faces tough competition from Russian home-grown alternatives. The country’s domestic tech industry is undoubtedly one of the most independent, with locally-built answers to platforms like Facebook, WhatsApp and Google coming in the form of VKontakte, Telegram and Yandex, respectively. Like much of the former USSR, programming and software design has become a critical area of focus, with thousands of well-trained graduates and comparatively low wages fueling the industry.

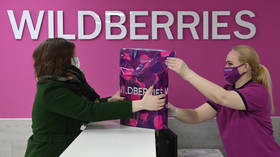

In e-commerce, it is no different. As well as China’s colossal Alibaba marketplace, the world of online shopping is carved up by companies like Ozon, which has a market capitalization of $13 billion, and Lamoda, a Moscow-headquartered fashion seller that has financial backing from a German conglomerate. For food and groceries deliveries, Yandex and Delivery Club, which predates its Western rivals, operate speedy dispatches that would rival or outdo anything available elsewhere for price and convenience. These pale in comparison, however, to Wildberries.

Owned by Russian entrepreneur Tatyana Bakalchuk, the online retailer is frequently hailed as the country’s own answer to Amazon. In 2019 alone, the platform’s turnover grew by 88%, taking its revenue to $3 billion. Customers reportedly placed an average of 750,000 orders a day, more than twice the total in the previous year. Offering everything from children’s shoes to televisions to household furnishings, the site has stayed lean, with only 48,000 employees and no external investors. The business has, in effect, become a one-woman empire and a regular feature in the daily lives of most Russians.

But, perhaps even more tellingly, Wildberries’ share of Russia’s e-commerce market, despite being twice that of its closest competitor, is only around 14%, with Russians often happy to shop around to determine the best price and supplier. In the US, by contrast, Amazon leads the field with around 40% of all transactions made through its service. The American firm may dabble in books and electricals and laundry detergent, but its real focus is the monopoly business. Its vast infrastructure and its unimaginable scale is only possible to sustain when it has a lock on significant amounts of consumers. So, to turn a profit in Russia, Amazon would have to not only compete with popular local success stories like Wildberries – it would have to steamroller them.

The fact that no one online retailer has an unassailably dominant position in Russia might be a worrying sign for Amazon when it comes to Russian shopping habits, but it has its upsides for the country’s economy. For years, activists and commenters have warned that the digital behemoth was gutting businesses and retailers on the high-street, and even those that tried to compete with their own online offerings. With its Amazon Prime offering, guaranteeing fast and free delivery for a fixed low price, the company makes it hard for buyers to justify placing orders with any other service, given they’re already paid up for shipping. As of April, 200 million people have now signed up, and evidence shows they spend more once they have.

The result, in many places, has been devastating. Hardware stores, bookshops and even local traders’ stations have seen the consequences of more and more customers going online. The ease of the single click has substituted family-run businesses and neighborhood startup joints for endless warehouses of low-paid workers with few rights. In Russia though, while significant numbers of transactions have moved online, there still appears to be a penchant for buying things in person, and no one firm has an automatic grasp on consumers.

Analysts found that retail growth improved in the country in the final months, beating expectations and playing a role in the post-pandemic recovery. While the pandemic did force more people to make purchases online – up 58% last year since 2019 – it clearly has not yet finished off in-person retail, and it is split broadly between multiple competitors.

However, even if Amazon has apparently little to offer Russian consumers at present, it could be a vital lifeline for businesses to sell their wares overseas in the future. A deal signed at the St Petersburg International Economic Forum on Wednesday gave the Russian Export Center and the country’s national postal service the opportunity to open an online showcase for domestically-made goods to be exhibited through the German Amazon marketplace. Using Russia’s mail system, products will be shipped directly to the European Union. “By 2024, there are plans to attract more than 500 companies” to the scheme, the statement concludes.

Russia, vast and with its own fierce local competitors, might seem to be unconquerable even for an e-commerce giant like Amazon. But the country’s economy, despite Western sanctions, will continue to become more and more integrated with the West. Even if it isn’t delivering brown packages by the truckload within the country, it might not be long before the business is shipping things out.

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!

Comments are closed.