Pinkerton: How Warriors Keep Their Honor Clean Even in Defeat

All Gave Some, Some Gave All

One of the most famous epitaphs in history was inscribed near a battlefield in Greece, some 2,500 years ago:

Go, tell the Spartans, stranger passing by,

That here, obedient to their laws, we lie.

These simple yet elegiac lines were written by the poet Simonides of Ceos to commemorate the heroic but doomed defense of Thermopylae in 480 B.C., as the badly outnumbered Spartans fought bravely and yet were eventually overwhelmed by the Persians. These poetic words were subsequently noted and recorded by Herodotus, remembered as the “father of history.”

It’s from the Battle of Thermopylae that we get, for example, the iconic words of defiance, molṑn labé (come and take them), which have been repeated many times since across the annals of military history, including at the Battle of Gonzalez in 1835, when Texian civilians, newly mobilized for battle, defeated the Mexican army.

Indeed, Thermopylae is one of the most famous events in the history of war, commemorated endlessly in the culture, including in the rousing 2006 Hollywood movie, 300.

A marble frieze depicting the Battle of Thermopylae marks the site where 300 Spartans held off hundreds of thousands of invading Persians in 480 BC. (AP Photo/Petros Giannakouris)

Persian archers kill the last of the Spartans at the Battle of Thermopylae in August 480 BC, as 300 Spartans, under King Leonidas, remained to the bitter end to defend the pass. (Engraving by Pinelli, photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The statue of King Leonidas of ancient Sparta towers over the battlefield of Thermopylae at sunset. The inscription on the statue’s pedestal reads: “ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ” (“Come and take them.”) (Getty Images)

For those who wish to be remembered in glory, courage in battle is a proven method. Indeed, Clio, the muse of history, often shows her favor to those who fight honorably, even if they don’t win or even survive. That’s why we Americans remember, for instance, in our own history, the valiant defenders of the Alamo in 1836, the last stand of General Custer in 1876, the doomed aviators of Torpedo Squadron 8 at Midway in 1942, and the embattled troops at Chosin Reservoir in 1950.

With these immortals in mind, we might recall what the British statesman Thomas Babington Macauley wrote of ancient Roman warriors:

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate:

“To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his Gods.”

To be sure, this is not an argument for fighting unnecessary wars. And yet even in an ill-conceived “war of choice,” the soldierly ideals of personal courage, group loyalty, and duty to the nation are always prized. And so we honor the 4,572 American GIs who died in Iraq, and the 2,298 who died in Afghanistan, as well as the tens of thousands who were wounded and the millions who served.

Indeed, for the past two decades, stateside Americans have witnessed an ongoing sacrament of sacrifice, punctuated, of course, by the 13 American servicemen and women who died at the Kabul airport on August 26.

An honor guard places the remain of Navy Corpsman Maxton W. Soviak, 22, of Berlin Heights, Ohio, into a transfer vehicle during a ceremony at Dover Air Force Base on August 29, 2021, for the 13 U.S. service members killed in the suicide bombing in Kabul, Afghanistan, on August 26. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Without a doubt, the Kabul evacuation had its tragic and heroic elements, even as, at the same time, it had its pathetic elements. To cite just one example of the pathetic, we might consider the chain of mistakes that brought us to the brink of disaster and humiliation in Kabul. For instance, there was the precipitous abandonment of the Bagram air field on July 1. For a long time to come, military historians will wish to study how it came to pass that the U.S. gave up the enormous—and easily defended, as it was out in the hinterlands—Bagram prior to the evacuation from the highly vulnerable Hamid Karzai airport in Kabul.

Yet even as historians study the mistakes made in situation rooms, they will also chronicle the effectiveness, as well as courage, on the ground.

In fact, given the depth of the strategic hole dug by higher ups, the actual evacuation from Kabul rates as a successful tactical operation; we got out with “only” 13 dead, as well as, of course, many injured. And so as a matter of successful logistics, the Kabul evacuation bids to take its place alongside other orderly retreats, including the Anabasis of antiquity, as well as U.S. exit from Hungnam, North Korea, in December 1950.

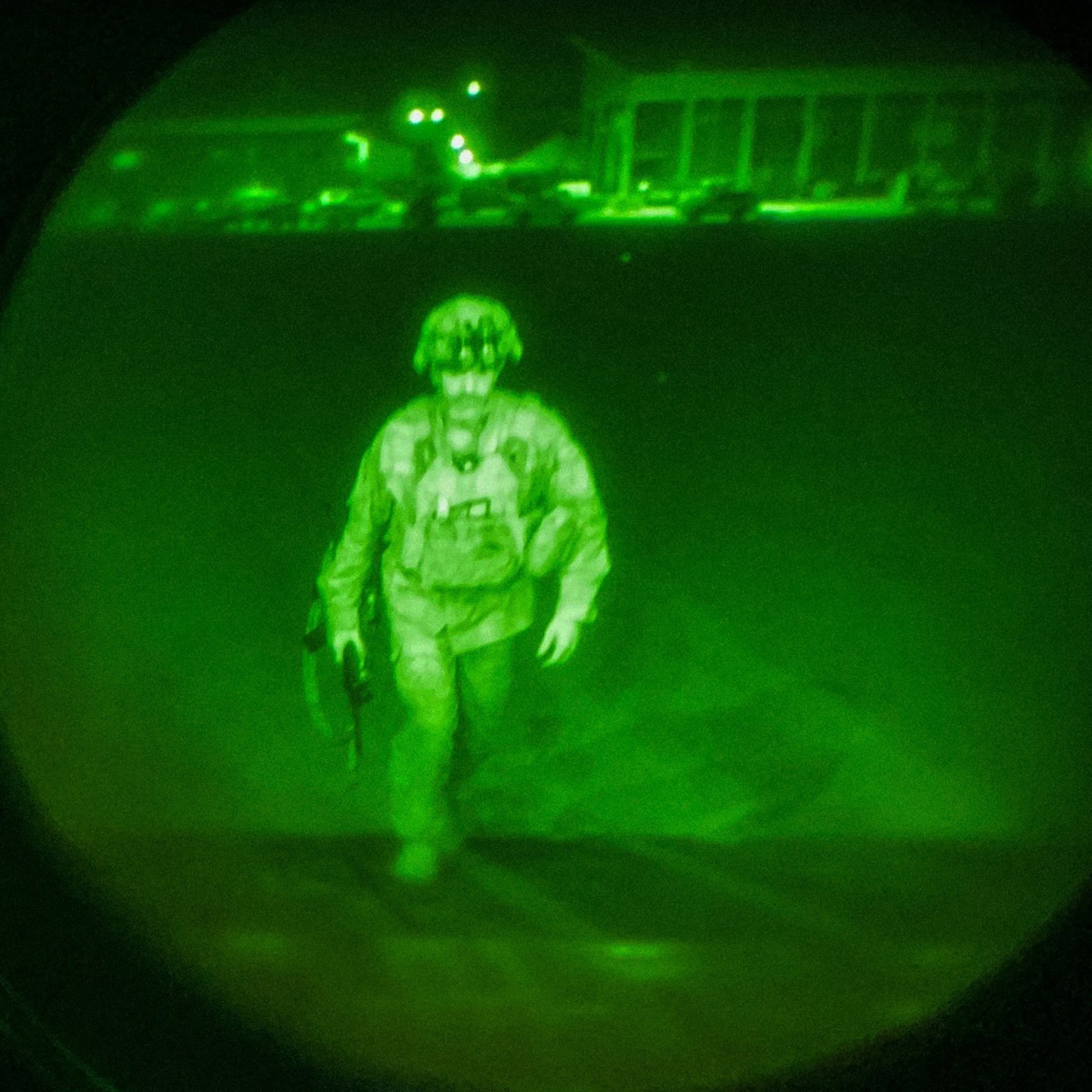

And so in 2021, there was no little redemption when we saw that the last American soldier out of Kabul was the actual commander of the operation, Maj. Gen. Chris Donahue. His was the honorable path to exit, and it was a path not without personal risk. (We might recall that Yonatan Netanyahu, the commander of Israel’s rescue/evacuation in Entebbe, Uganda in 1978, made sure that everyone else was on the escape plane—and then, just as he himself was about to board, he was shot dead by a sniper.)

So we can see: Unto the last, if need be, the best soldiers are servant leaders, putting everyone else ahead of themselves, while always keeping their own chin up.

Indeed, precisely because being tempered by fire—in either victory or defeat—means so much to so many, it’s little surprise that veterans of the Great War on Terror (GWOT) in both parties have taken on civilian leadership positions; according to one estimate, there are currently 50 GWOT vets in Congress. Be they red or blue, interventionist or non-interventionist, they share a common and hard-earned perspective on the value of service and on the cost of war.

To be sure, only time will tell how well veterans will do in public life; and yet in the meantime, those still in the service are trying harder.

U.S. service members with 82nd Airborne Division prepare to board a C-17 aircraft out of Kabul, Afghanistan, on August 30, 2021, ending the 20-year war. (Senior Airman Taylor Crul/U.S. Air Force via AP)

U.S. service members with the 82nd Airborne Division board a C-17 cargo plane to depart from Kabul, Afghanistan, on August 30, 2021. (Senior Airman Taylor Crul/U.S. Air Force via AP)

U.S. Army Maj. Gen. Chris Donahue, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, XVIII Airborne Corps, boards a C-17 cargo plane on August 30, 2021, in Kabul, Afghanistan, as the last American service member to depart the country. (U.S. Central Command via Getty Images)

Lessons Learned the Hard Way

Yet an effective military is about more than just honor, as vital as that is. It’s also about learning lessons and figuring out how to do better. As the Wall Street Journal’s Peggy Noonan wrote earlier this month:

The enlisted men and women of the U.S. military are the most respected professionals in America. They can break your heart with their greatness, as they did at Hamid Karzai International Airport when 13 of them gave their lives to help desperate people escape. But the top brass? Something’s wrong there, something that August revealed. They are all so media-savvy, so smooth and sound-bitey after a generation at war, and in some new way they too seem obsessed with perceptions and how things play, as opposed to reality and how things are.

Yet in between the ranks of the enlisted solders and the general grade officers are the field grade officers—and at least one of these is speaking out. On August 26, Marine Lt. Col. Stuart Scheller posted an item on Facebook, declaring, “The reason people are so upset on social media right now is not because the Marine on the battlefield let someone down. . . . People are upset because their senior leaders let them down, and none of them are raising their hands and accepting accountability or saying, ‘We messed this up.’” On August 31, Scheller resigned his commission. Let’s hope that in his new life as a civilian, he will have still more opportunities to speak out.

And here’s another GWOT vet voice, that of retired Army colonel M.E. Johnson, writing in the Los Angeles Times on September 3:

Our warriors expected to be told the truth. They got lies. If our military and civilian leadership did learn something from Vietnam, it was how to deceive Americans. The “Afghanistan Papers,” obtained by The Washington Post, document “explicit and sustained efforts by the U.S. government to deliberately mislead the public …. [I]t was common at military headquarters in Kabul — and at the White House — to distort statistics to make it appear the United States was winning the war when that was not the case.”

And in those Afghanistan Papers, published in 2019, Lt. Gen. Douglas Lute, the Afghan war “czar” in the Bush and Obama administrations, was quoted as saying, “We were devoid of a fundamental understanding of Afghanistan—we didn’t know what we were doing. . . . We didn’t have the foggiest notion of what we were undertaking.”

Lute’s comments are key because they remind us that even at the top of the military hierarchy there’s an understanding, however belated, that something went wrong—badly wrong.

In that same vein, Adm. Mike Mullen, the retired chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, admitted last month that the military had been too quick to suspend its own judgment and too quick to salute impossible orders: “We need to examine in the military that can-do spirit, and can we understand why we too often say yes to a mission when we should say no, nobody wants the Saigon image, and obviously we ended up with another Saigon image.”

Mullen, of course, helmed the uniformed military from 2007 to 2011, during which time President Obama launched his ineffective surge in Afghanistan. So perhaps sometime in the future, senior officers will follow the advice, if not the example, of Lute and Mullen and resign in protest, as opposed to simply going along to get along. In the meantime, we at least have the sterling example set by former Lt. Col. Scheller.

Still, history tells us that over time militaries learn lessons. A crop of bad generals is often replaced by better generals, determined to rectify the old mistakes. Indeed, the American military has been on the whole quick to learn lessons. To illustrate, we can start with the bleak moment in our history that Mullen cited, the “Saigon image.” He was referring, of course, to the evacuation of Americans and others from Saigon, South Vietnam, in 1975.

Just about everything that can be said about the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq was also said about the war in Vietnam. And while there’s no need to rehash all that here, suffice it to say that brave troops were poorly directed by the civilian leadership—most obviously, President Lyndon B. Johnson and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara—and were also poorly led by their own uniformed commanders.

Yet there’s one thing about the U.S. military: It doesn’t like to lose. In fact, in 1973, even before the fall of Saigon, Gen. William DePuy took charge of a new formation, the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command. Tradoc, as it’s called, was founded on an important premise: The Army and the entire military needed to get smarter; and to get smarter, it had to study harder. And so Tradoc runs dozens of schools teaching hundreds of courses to hundreds of thousands of Army students.

Portrait of General Edward C. Meyer by Everett Raymond Kinstler (U.S. Army Center of Military History)

In addition to DePuy, another important figure in the Army’s comeback was Gen. Edward “Shy” Meyer, who served as Army chief of staff from 1979 to 1983. Meyer was just 50 when he was appointed to that top post; he was chosen over at least 15 more senior officers. Having inherited an Army that was “hollowed out” by defeat and demoralization, Meyer whipped it into shape. He added two weeks to basic training, while at the same time, he increased pay and educational opportunities.

Needless to say, Ronald Reagan, sworn in as our 40th president in 1981, helped immeasurably. He was a champion of strong defense, and yet at the same time, he was alert to new ideas, such as the Strategic Defense Initiative launched in 1983.

And yet even in the years prior to Reagan’s presidency, the beginning of the Army’s comeback and the military’s had already begun. That comeback was the result, first, of an internal desire for reform, of the military’s desire to learn and apply lessons. And that’s how we got to the recent apogee of our national strength, namely our quick-but-limited victory in 1991’s Operation Desert Storm.

So this is how the military keeps its honor clean. In the field, its general officers go last, as was the case with Chris Donahue in Kabul.

And on the homefront, general officers think on past mistakes and learn new lessons, always putting the troops first, as was the case with Shy Meyer at the Pentagon.

Some day soon, there will be a monument to the heroes of Afghanistan, dutiful always even in the midst of folly. And perhaps the inscription will read:

Go, tell the Americans, stranger passing by,

That here, obedient to their orders, we lie.

If so, every soldier, every political leader—and every American—could see those words and resolve: We will pause to remember our past fallen, even as we plan ahead for future betterment and future victories.

Two laurel wreaths rest atop the commemorative stone on Kolonos Hill, the site where 300 Spartans made their final stand at the Battle of Thermopylae. The stone is inscribed with the words of Simonides’ famous epigraph: “Go tell the Spartans, passerby, that here, obedient to their laws, we lie.” (Photo by Andy Hay/Flickr)

Comments are closed.