Pinkerton: Five Hard Lessons from America’s 20-Year Journey Since 9/11

The Road to Here

After 9/11, it seemed that we were in a battle against evil. And without a doubt, Osama Bin Laden was evil. And yet strangely, the American government chose not to focus on him or even on al Qaeda.

Instead, the U.S. became engaged, embroiled, and then quagmired in Afghanistan and Iraq. In the meantime, Bin Laden himself, having used mostly Saudi Arabians (15 of the 19 hijackers were from Saudi Arabia, none were from Afghanistan or Iraq) and Saudi money to perpetrate 9/11, was hiding out in Pakistan.

Undoubtedly, the Pakistani government knew exactly of Bin Laden’s whereabouts, and yet it happily collected more than $20 billion in U.S. foreign aid between 2001 and 2011, while all the time keeping Bin Laden’s secret. That’s how badly we were played, and now top Pakistani officials are crowing about their victory in the long game, as they, not us, control Afghanistan.

We finally managed to kill Bin Laden in 2011, which was right and just, and yet by then we were so committed to “nation building” in Iraq and Afghanistan that we stayed in Afghanistan for another decade.

Now we’re gone from Afghanistan—having been booted out in a humiliating way—and yet we’re still doing… something in Iraq, Syria, and who knows where else in in the Middle East, Central Asia, and Africa.

So are we starting to see something wrong with this picture?

It took Americans awhile to figure out the full depth of the foreign policy elite’s mishandling of the last two decades. Indeed, historians of the future will puzzle over how our supposed “best and brightest” could become so misdirected as to a question as as basic as the location of our true enemy.

The World Trade Center, September 11, 2001. (Tim Dillon-USA TODAY)

The events of Monday, September 11, 2001, began with tragedy, which was soon laced with inspiration and even a tragic kind of uplift, as we saw the New York City firefighters and police officers—hundreds of them—go to their deaths to try to save others.

And soon we learned the story of Todd Beamer, who led the courageous counter-attack aboard Flight 93, causing it to crash into a field in Pennsylvania, as opposed to the terrorists’ intended target, the U.S. Capitol.

And we learned about Betty Ong, the flight attendant abroad a plane hijacked from Boston that crashed into one of the World Trade Center towers. Ong could not stop the forthcoming carnage, but as she called in from the plane, her cool and informative voice provided a sort of first-hand commentary on the unfolding events, as authorities scrambled to do something and failed. For years thereafter, American GIs on their way to hot zones would listen to the tape of Ong’s voice to remind themselves why they were fighting.

An American flag is posted in the rubble of the World Trade Center, on Thursday, September 13, 2001, after the 9/11 attacks. (AP Photo/Beth A. Keiser)

In fact, we scored a quick and relatively easy victory over the Taliban in late 2001, although disturbingly, Bin Laden slipped through our fingers. How did that escape happen? The Wall Street Journal’s Peggy Noonan’s speculated that the Bush administration and its Pentagon strategists had eyes on a bigger prize, as they saw it, than Bin Laden’s scalp. “Maybe,” she wrote on August 26, “they consciously or unconsciously knew that if they got the guy who did 9/11, killed him or brought him to justice, that would leave a lot of Americans satisfied that justice had been done. That might take some steam out of the Iraq push. Maybe they concluded it would be better not to get him, or not right away.”

Noonan was referring, of course, to the Bush administration’s real goal, which was regime-change in Iraq. Is Noonan correct in her suspicion? As noted, there will be plenty for historians to puzzle over. The 2009 Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s report on how Bin Laden was able happened at Tora Bora will certainly provide them many clues.

Still, for about a year, the tragically uplifting Spirit of 9/11 united Americans.

Firefighters unfurl an American flag from the roof of the Pentagon the day after hijackers flew a plane into the Pentagon on September 11, 2001. (AP Photo/Ron Edmonds)

And then came the enlargement of American ambitions. President George W. Bush declared that exacting revenge on the Taliban—although again, not Bin Laden himself—wasn’t good enough, and that the U.S. must now expand its ambitions to include dealing harshly with not only Iraq, but also with Iran, North Korea, and their aiders and abettors. As Bush had said, “Either you are with us or you are with the terrorists.” (This author could see where things were heading as soon as he heard Bush’s “Axis of Evil” speech in January 2002, and expressed his opposition to the looming war with Iraq on many occasions in 2002-3, including here, here, and here.)

In October 2002, Bush put war with Iraq to a vote in Congress, and big majorities went along, including Democrats Hillary Clinton, John Kerry, Chuck Schumer, and Joe Biden. Yet by now, the Spirit of 9/11 was dissipating, to be replaced by a much different spirit, the ideology of the Bush Doctrine calling for preemptive wars of choice.

So we went to war in Iraq in March 2003. And we realized, only too late, that Saddam Hussein had no weapons of mass destruction, that we would not be “greeted as liberators,” and that the war would not be a “cakewalk.” And so Iraq turned into a kind of Vietnam—a bloody slog for no obvious purpose.

Nasariyah residents protest the presence of U.S. troops in Iraq on April 15, 2003, just days after U.S. coalition forces took control of the country. The rally of around 20,000 mostly Shiite Muslims, unthinkable just a week ago under Saddam’s Sunni Muslim regime, chanted: “Yes to freedom! Yes to Islam! No to America! No to Saddam!” (CRIS BOURONCLE/AFP via Getty Images)

U.S. soldiers stand guard near the burning wreck of a U.S military vehicle caught in the explosion of a car bomb attack on September 5, 2005, in Baghdad. (Akram Saleh /Getty Images)

Yet for his part, President George W. Bush kept pushing into the Big Muddy. Indeed, by 2005, he doubled down, even quadrupled down, declaring in his second inaugural address that the United States would move toward “the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.” Skeptics could ask: If we couldn’t reliably liberate Fallujah, despite the loss of hundreds of soldiers, what chance did we have at liberating Iran, Russia, China, and all the other tyrannies?

Bush’s hubris soon met the predictable nemesis, although, of course, he himself paid no physical price. The real cost in American blood was borne by our fighting men and women, and yet in a real sense, the nation too was injured. In the opinion of much of the world, we were bloody fools.

In the meantime, in a different way, the Republican Party suffered too. It was clobbered in the 2006 midterm elections, and then again in the 2008 presidential election. That latter contest, of course, paired Barack Obama, who had called Iraq a “dumb war,” against John McCain, who not only supported the war in Iraq, but also wanted to extend the fighting to Iran. Obama won easily, as even red states such as Indiana turned against McCain’s bombastic hawkery.

Yet once he was in office, Obama chose to expand the Afghanistan War. In fact, two-thirds of the casualties America suffered in Afghanistan came during his presidency.

U.S. Army soldiers from the 101st Airborne division offload during a combat mission on March 5, 2002, in Eastern Afghanistan. (Keith D. McGrew/US Army/Getty Images)

U.S. Marines walk to their helicopter on July 2, 2009, in Helmand Province, Afghanistan. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

U.S. Army soldiers carry a critically wounded American soldier on a stretcher to an awaiting MEDEVAC helicopter on June 24, 2010, near Kandahar, Afghanistan. (Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

By now the unifying Spirit of 9/11 was long gone. As we have seen, it was pushed aside by the divisive Bush Doctrine, which was itself then replaced by a new kind of uniting spirit: the grim Anxiety of Endless War.

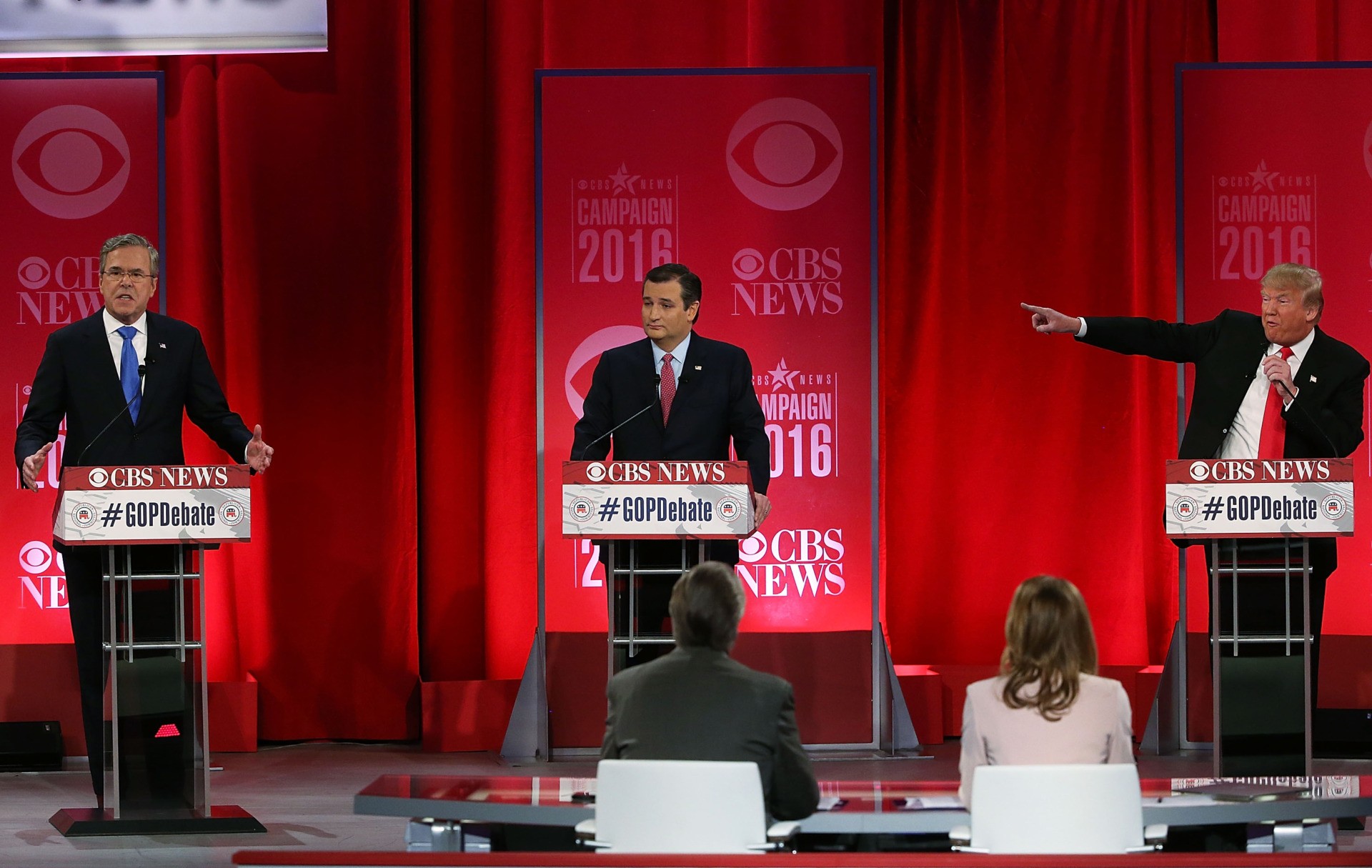

During the 2016 presidential campaign, candidate Donald Trump astounded and electrified audiences with his denunciation of Bush and the Iraq War. To the amazement of the media pundits and the foreign policy panjandrums, most Republicans, even in hawkish South Carolina, agreed with Trump’s anti-interventionism.

The Republican primary debate in South Carolina on February 13, 2016, when then-candidate Donald Trump called out candidate Jeb Bush’s brother, former President George Bush, for his handling of 9/11 and the subsequent wars. (Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

It was, after all, the American middle class that had borne the burden; the folks were done with the high-blown rhetoric about liberating the world. Real people cared about Middle America, not the Middle East. They wanted out, albeit they wanted an honorable exit, not an abject flight.

And now, of course, in 2021, it’s all come crashing down—we got the abject flight.

Americans who were not even born on 9/11 were still in Afghanistan nearly two decades later. Indeed, at the end, they had the task of making the best of the Biden administration’s disastrously ill-planned mission aimed at evacuating as many Americans as the Taliban would allow.

Without a doubt, the closing fiasco in Kabul has put an indelible stain on the Biden presidency. Even in a blue state such as New Jersey—home, of course, to plenty of veterans and patriots—Biden was heckled: “Best friend died in 2011 Afghanistan for what?” “Leave no American behind!”

C-SPAN

Yet as the 18th century economist Adam Smith said after learning of a British defeat, “There is a great deal of a ruin in a nation.” That is, countries can suffer a lot, and yet still survive and even flourish. So we can mourn our losses, measure the damage, and then resolve to change course.

The Road From Here

Yet in order to do better in the future, we must first stop making mistakes and learn to think more strategically about next steps. And so herewith, as a contribution to the debate—and hopefully to better understanding—are five hard lessons of 9/11 and the years thereafter.

1. We’re back to square one on homeland security.

We have to keep doing now what we did not do before 9/11, which is properly defend the United States.

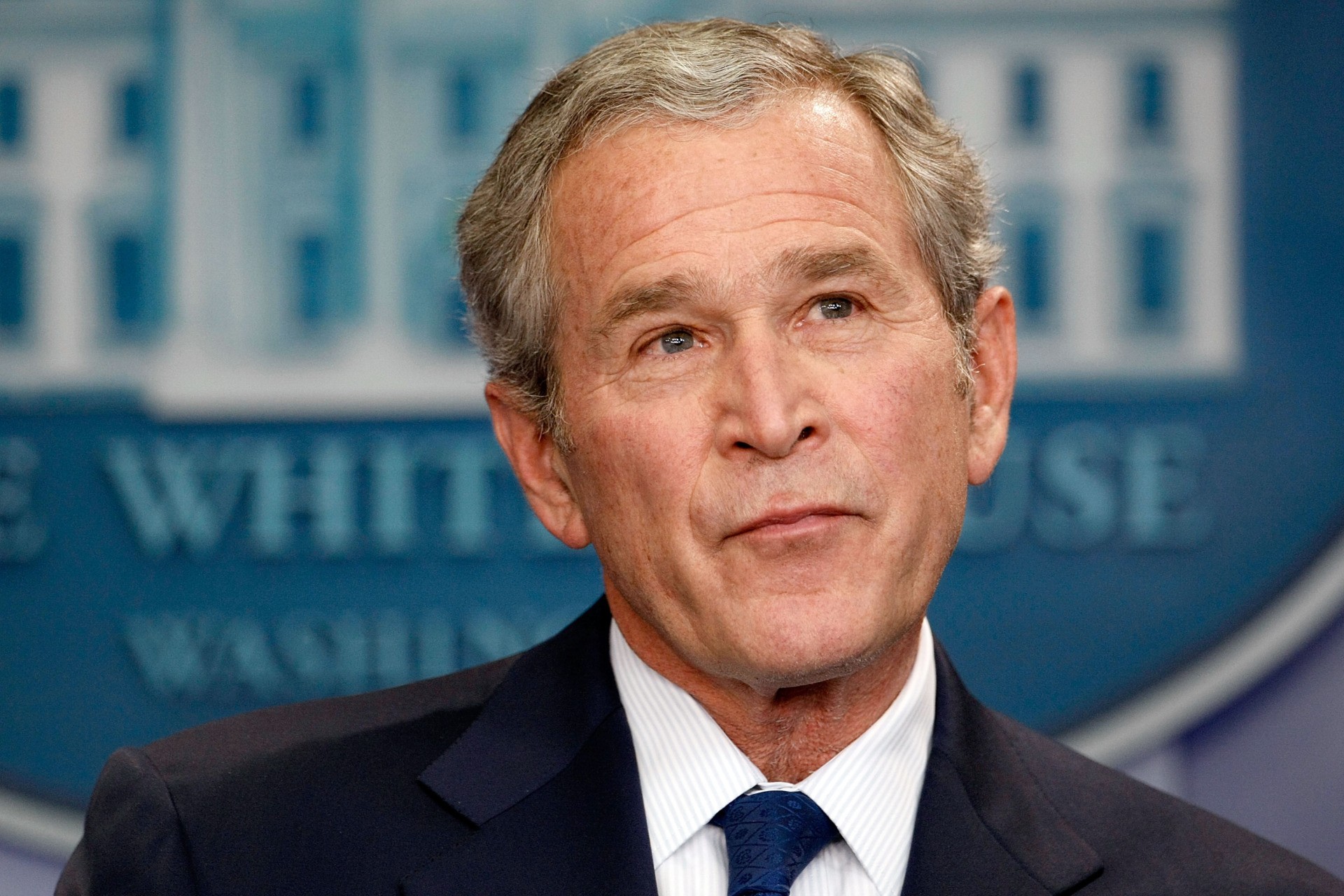

A month prior to 9/11—on August 6, 2001, to be exact—President George W. Bush received the Presidential Daily Brief (PDB), including the headline, “Bin Ladin Determined to Strike in US,” and the follow-up words noting “patterns of suspicious activity in this country consistent with preparations for a hijacking.” This was, in fact, the 36th time in 2001 that the PDB had mentioned Osama bin Laden or al-Qaeda. Bush’s reported response: “All right. You’ve covered your ass now.”

We can assume that presidents since have taken the PDB more seriously.

George W. Bush holds his last press conference as president on January 12, 2009, in Washington, DC. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

In fact, the recent record suggests that the changes that the U.S. has made on the homefront—most obviously, the creation of a whole new Department of Homeland Security in 2002—have worked to keep us safe. Some of those changes have been wide-ranging, such as the PATRIOT Act, and yet others have been simple, such as the Federal Aviation Administration’s decision to mandate, after years of opposition, the armoring of cockpit doors on passenger planes.

Yet now that we are no longer “taking the war to the terrorists”—at least not in Afghanistan—we will have to stop pretending that we can defeat “terror” by fighting in some overseas quagmire. Instead, we can redouble our resolve to stay vigilant here in the U.S. Yes, it was always a misnomer to think that American military operations in faraway countries had much to do with thwarting terrorism here in the U.S. After all, the actual 9/11 attack was planned primarily in Hamburg, Germany, and secondarily in San Diego, California. Back in Afghanistan, the Saudi Arabia born-and-financed Osama Bin Laden was a cheerleader, not a ringleader.

So the hard work of counter-terrorism is always better done by the police and police-like officials, as opposed to by B-52s and the 82nd Airborne.

U.S. Army Paratroopers assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division leave Pope Army Airfield, NC, to deploy to the Middle East in response to events in Iraq on January 1, 2020. (Capt. Robyn Haake / US ARMY / AFP via Getty Images)

2. There’s no end to history.

Back at the turn of the century, many among the elite were deeply influenced by Francis Fukuyama’s 1989 essay in which he declared “The End of History.” By that Fukuyama, an American armed with a Ph.D., meant that the world had arrived at the point where the political debate was over: Everyone now agreed that Western-style democratic capitalism was the best. As he wrote, we were seeing “The end-point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” In other words, our system was the only paradigm, the wave of the future. For an American, that was a nice night thought, and yet to put it mildly, others around the world did not agree.

Indeed, the question as to how anyone could have agreed with such giddy optimism will be yet another question over which future historians will puzzle. Still, for awhile there, Western elites thought that way; and so they fought that way to try and make the Fukuyama dream come true in countries such as Afghanistan and Iraq. (Actually, the elites didn’t fight at all—they sent John and Jane Public.)

Yet in fact, there was no end to history. History was and still is being made by peoples and countries who have never had any interest in what an American professor might think about them and their ways. Indeed, in history, few essays were as widely read—and then as decisively disproven—as Fukuyama’s.

3.“Moral clarity” is no substitute for realistic thinking.

George W. Bush and his acolytes seemed to think that what they called “moral clarity” could be a substitute for practical real-world acuity.

In fact, what we always need is realism. Ronald Reagan was a moral man, as fully committed to American ideals as any other great U.S. president, and yet he always understood the need to realistically—that is, intelligently and strategically—match goals with means. To put that another way, as a matter of geopolitics, America should only fight for goals that we had the means to achieve.

The inability to realistically calibrate the art of the possible was a hallmark of our failure in Iraq and Afghanistan. We were ordering our troops to do what couldn’t be done, namely, to nation-build, even as they fought. As a Pentagon document from 2009 instructed, “Field Manual (FM) 3-24 Counterinsurgency states, ‘Soldiers and Marines are expected to be nation-builders as well as warriors.’” Good luck with that.

U.S. troops guarding the entrance of the U.S. administration’s offices in Baghdad argue with ex-Iraqi army personnel staging a protest on June 18, 2003, about two months after U.S. coalition forces gained control of the country. (RAMZI HAIDAR/AFP via Getty Images)

And of course, a proper understanding of means must begin with the American people. Wise leaders should have asked: What level of effort will the citizenry support and sustain? After all, a policy that looks great on a PowerPoint isn’t so great if it can’t gain the prolonged agreement of the populace and so can’t be carried out.

That’s what happened in Afghanistan. The “best and the brightest” supported the war long after the masses had stopped supporting it. One poll from early July found that 70 percent of Americans supported getting out of Afghanistan. By contrast, a poll of support for the war among, say, the membership of the Council on Foreign Relations, would have likely shown the opposite.

So while Joe Biden has taken a deserved pounding for the cluster-effed nature of the withdrawal in late August, support for a return to Afghanistan is, shall we say, scant. This August 31 headline from NBC News gets it right: “Polls: Americans back end to Afghanistan war but fault Biden’s execution.” Indeed, another recent poll showed that by a margin of more than 2:1, Americans say that the Afghan war wasn’t worth it. Moreover, yet another poll taken earlier this month found that “war and foreign conflicts” rank 11th Americans’ list of concerns.

But okay, enough of polls, what do ordinary people think? What do they themselves say in their own words? The New York Times interviewed some regular folks in Hacienda Heights, California, including Brenda Ortiz, who said of the Afghan war, “I don’t think it was ever going to be easy to leave.” And yet as she watched her kids play soccer, she added, “At the end of the day, our country is where we need to be focusing. We have our own issues: getting the kids to school, healing our communities. It’s not our war to fight anymore.”

It’s always important, albeit difficult, for the political elites to remember: They work for the American people. And so if the elites can’t convince folks that a war is worth fighting, then America shouldn’t be fighting.

Taliban fighters at a rally in Kabul on September 11, 2021, where they triumphantly marched with what appears to be U.S. military gear on the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. (AAMIR QURESHI/AFP via Getty Images)

Taliban fighters escort veiled women during a pro-Taliban rally in Kabul on September 11, 2021, triumphantly marching with what appears to be U.S. military gear on the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. (AAMIR QURESHI/AFP via Getty Images)

4. The silver lining: Our allies will have to step up to defend themselves.

Writing on the relationship between the U.S. and Europe in the wake of Afghanistan, the Voice of America (VOA) observed that in the U.S., there is “now an overwhelming political constraint on military interventions.” To which we should say, good.

In the meantime, as soon as our allies realize that America will no longer unquestioningly be on the hook for all their military needs, they will likely try harder to defend themselves. As the VOA piece noted, the U.S. spends about 3.4 percent of GDP on defense while the 27 members of the European Union spend just 1.2 percent. Today, the U.S. has more than 64,000 military personnel in Europe, as well as nearly 17,000 civilians.

Not to put too fine a point on the matter, the Europeans have gotten soft. They don’t spend much on defense because they know we will. For decades now, U.S. presidents have been nudging the Europeans to spend more on their own defense, and yet they never have for a simple reason: They don’t have to. They are free riders, enjoying the geopolitical equivalent of no-strings-attached welfare. And it’s had the predictable effect of making them dependent—albeit, of course, not overly grateful because after all these decades they see American defense as an entitlement.

Men and women soldiers from different nations march in the opening ceremony at the 2018 NATO Summit at NATO headquarters on July 11, 2018, in Brussels, Belgium. Leaders from NATO member and partner states faced strong demands from U.S. President Trump for NATO member countries to spend more on their own defense. (Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

Yet now, the VOA article concludes, the Europeans are going to have to face up to the prospect of actually stepping up for the sake of their own defense. This point was made by Gerard Araud, a former French ambassador to the U.S, who wrote recently in The Economist, “At a time when Ukraine, Syria, Libya and north Africa’s Sahel region—that is, Europe’s closest neighbors—are ablaze and America is losing interest, the European Union should be capable of dealing with these crises itself, including militarily.” Including militarily. Key phrase.

We can add that the same phenomenon is now visible in Japan. The Japanese currently spend even less of their wealth on defense than the Europeans, about 0.9 percent. Yet that fractional percentage seems destined to increase, as Japan confronts China, while no longer being sure that the U.S. will put itself in the middle of any dispute between Tokyo and Beijing. Soon enough, the world will likely be reminded that Japan has a robust martial tradition. That tradition has been sleeping for the past 76 years, and yet it likely will re-awaken. If so, then Japan could take the place of the U.S. as a counterweight to China in the western Pacific. Good.

So this is the silver lining of the Afghan debacle: Our friends will be less like deadbeat dependents and more like… strong allies.

5. We can snap out of it, if we’re willing to do the work.

Ross Douthat, a lonely conservative at the New York Times, wrote on August 31 that we should take drastic action in the wake of Afghanistan:

Our botched withdrawal is the punctuation mark on a general catastrophe, a failure so broad that it should demand purges in the Pentagon, the shamed retirement of innumerable hawkish talking heads, the razing of various NGOs and international-studies programs and the dissolution of countless consultancies and military contractors.

We can note that it’s not every day that a New York Times columnist uses words such as “purge,” “raze,” and “dissolution” to refer to pillars of the Establishment.

President Joe Biden checks his watch during a ceremony to transfer the remains of the last U.S. service members killed in the Afghanistan war on August 29, 2021, at Dover Air Force Base. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Now a cynic might predict that nothing will change; that is, the Establishment, having failed so badly, will simply give itself a pay raise and then go about plotting the next globalist debacle. And yet such marching-to-folly can’t last forever; there’s a limit to how many times a great power can fail and still be a great power—or a power of any kind. Indeed, the fall of the Western Roman Empire back in 476 A.D. sets a template in Western minds: It can all come crashing down. It’s happened before, and it can happen again.

Yet at the same time, history also reveals hopeful precedents of peoples who confronted a dire crisis and pulled themselves out of their tailspin.

Indeed, in its relatively brief history, the United States has confronted four existential foreign policy/national security crises spaced roughly 50 years apart. These were, first, the War of 1812 (Washington, DC, being captured and burned is a really bad outcome); second, the Civil War; third, the Depression and World War Two; and fourth, the “malaise” of the 1970s caused by the energy crisis, the defeat in Vietnam, and the surging threat from the Soviet Union. Yet in each of those instances, we got our bleep together, and so we came back bigger and stronger.

So now we’re in a fifth crisis. We’ve suffered a self-inflicted disaster. Today, China is menacing us and the rest of the world. So we’re going to need to rethink and reconstruct.

Unfortunately, history — never-ending thing that it is — offers no guarantee that we can recover. And yet fortunately, we’ve shown in the past that we can recover.

And in fact, the best indicator that something can happen in the future is that it’s happened before. And so if we’ve recovered four times, there’s ample reason to think that we can recover for a fifth time.

So let’s put on our thinking caps. And let’s also say a prayer.

What a long strange trip it has been. And yet we’re still Americans. And so there’s still hope. There’s always hope.

The Statue of Liberty shines on September 11, 2021, near the Tribute in Light as part of the commemoration for 20th anniversary of 9/11. (ROBERTO SCHMIDT/AFP via Getty Images)

Comments are closed.