I Had Seen What ‘Lock and Load’ Meant to This Drunk and Rowdy Rabble, and I Wanted Out

By the time “Let’s lock and load the ensign” reached a crescendo, I was already crawling under the chief club’s tables, hoping for a quick reprieve from the chief petty officer’s initiation. It was Friday afternoon, 14 March 1980, at Naval Station Guam. I had seen what “lock and load” meant to this drunk and rowdy rabble, and I wanted out.

A brand-new ensign, the Navy’s lowest officer rank, I had reported shortly before to be the base’s administrative officer. I was 22, far from Jersey, and the only woman officer in the southern half of Guam. As I would discover, becoming a chief was not just a promotion but a closely held rite of passage from sailor’s dungarees to chief’s khaki. It was a life changer, a military class status changer. Its concluding event, the mock court, proved more trying than any college Greek life event.

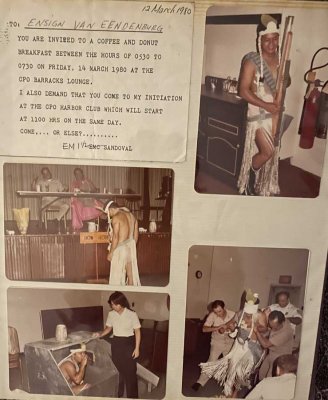

A page from Reinetta Vaneendenburg’s 1980 scrapbook shows a sailor at Naval Station Guam dressed as a princess as part of his chief petty officer initiation. Reinetta Vaneendenburg assists him as he sits in an ice chest. Photo courtesy of the author.

Only now can I share details of the chief’s initiation, since it is no longer practiced in this freewheeling and, to some, chaotic manner. This was “Old Navy,” with its emphasis on secrecy, drinking, and sexually disparaging language and acts.

But it sure was fun.

I should know: I was the “defense attorney” for an electrician’s mate first class petty officer, the only naval station sailor to be selected for chief that year.

The weeks that led up to his promotion were hectic for the petty officer. He guarded his charge book, a standard issue green journal, from chiefs who tried to defile or steal it. He was tasked with visiting each chief in the command for their advice. Their written comments served as “charges” for his trial and “convictions” in the Chief’s Court, the culmination of his six-week ordeal. He also had a myriad of obscure details to uncover before then.

Which Pacific Island had a Statue of Liberty? Who was the Navy’s first chief? What are the coordinates of the on-base goat locker, their private meeting site? Its lock combination?

Guam was a small tropical island, and it was before the internet and cell phones made short work of such matters.

That Friday morning at the Harbor Chiefs Club, a chief boatswain’s mate was the only person I recognized among the sea of tan uniforms. “Boats” headed security for the base, but today wore a huge aluminum foil star that said “Bailiff.” At 1100 hours, he opened the double doors to a large room with a table on its stage. A red-and-blue carnival wheel stood to the left. Sheets covered odd shapes, like gym or garden equipment, on the floor.

I was directed to a seat in front. I patted my pockets. One had the letter naming me as the petty officer’s defense attorney and the other cash, to defray fines if my jurisprudence failed.

Boats called, “All rise,” as two chiefs sauntered on stage.

The base legal officer, a lieutenant, sat behind me.

“Van, have your letter?” he whispered.

“Yes, thanks, lieutenant, for writing it.”

“Sure,” he said. “You know those guys on stage? No? Senior Chief D—, in the pink cape, he’s the judge. I don’t know the other guy, maybe the court recorder? Boats, as bailiff, collects the money and keeps everybody in line.”

A bowling ball rolls—slowly—toward a new chief petty officer as part of his 1980 initiation. Photo courtesy of the author.

“So many chiefs,” I said, looking around.

“Yeah, it’s an annual booze-up,” the lieutenant said. “Here comes Master Chief S—.”

“He’s the one who asked me to be the petty officer’s attorney,” I said.

There was a commotion at the door, followed by a near-naked man pratfalling into the room. The petty officer. A straw skirt fell to his bare feet and a white headband held long, white braids—an island princess.

“Present and accounted for, Your Royal Highest Honors,” he yelled as everyone laughed.

Boats pointed to an orange “bow here” sign. The petty officer bowed.

I turned to the lieutenant. “Where are the other officers?” I asked.

The lieutenant shrugged. “You had to be invited.”

“For the last time,” the judge boomed, “where’s your legal counsel?”

“Hey, you’re on,” the lieutenant said.

“Your Honor—,” I stammered as I stood up.

“Ensign, do not speak unless directed to do so.” The judge pounded a gavel on the table. “Five dollar fine to teach you some manners!”

“But—”

“Double that!”

I gave a $10 bill to Boats, the first of many sawbucks that day—a fine for my feistiness or public agreement of my deficiencies. It seemed everyone had contributed by the time the trial ended three hours later.

“Ensign Van is my defense attorney,” the petty officer volunteered.

“A fresh-caught ensign?” the judge said. “Ha! Where’s proof? A law school diploma would satisfy the court.”

“Here,” I said, handing the document to the judge with a flourish, “authorization to practice law today.”

“What stupidity is this?” the judge cried, waving the paper.

“May it please the court,” I said, “it is notarized.”

The judge crushed the letter and threw it at me, shouting choice words about my parentage, that I impersonated an officer, and how I fouled his court. What was his Navy coming to? Not the Whiskey Sierra Navy?

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

I knew W.S. was just one of the fleet’s disparaging terms for women in uniform. Wasted Sperm—a dig at our noncombat roles on the periphery of the Navy’s mission.

Boats collected cash while the judge harangued the lieutenant.

“Lieutenant, how can you, a real lawyer, prepare something rife with fallacious and felonious falseness?”

The revelry drowned out the lieutenant’s response.

“The court fines you $20!”

And so the fun began. A chief spun the Wheel of Truth to direct the initiate’s actions. One by one, the sheets were removed to reveal character-building learning aids. It would be a trial of nerves.

To build fortitude, the petty officer climbed into an industrial ice maker and answered questions, sang, or yodeled while ice fell over him until his teeth chattered.

He demonstrated the importance of leading by example with string that could not be pushed forward, only pulled. For the next test, he sat with his legs spread at the base of a small slide, anticipating that the bowling ball at its top would smash into him. The petty officer wore a blindfold. A sailor stopped the ball midway down the slope, then allowed it to gently roll down.

Today’s chief initiation and pinning is more formal than it was in the “Old Navy,” according to the author. Here, U.S. Navy sailors stand to sing “Anchors Aweigh” during a chief pinning ceremony at Santa Rita, Guam. Chief selectees go through a six-week initiation before being frocked as a chief petty officer. Photo by Mass Communications Specialist Seaman Chase Stephens, courtesy of the U.S. Navy.

The petty officer’s bravery was much cheered and ballyhooed.

The most ingenious ruse of the day involved glass. The petty officer saw a six-foot plastic strip that had been strewn with glass shards, and upon which he had to walk to prove his manliness. He once again wore the blindfold as he hesitantly complied. Imagine his surprise when the blindfold was removed. What had he walked on?

Potato chips.

He had to place his face in a trough to find the chief anchor pins in its slumgullion of candy, vegetables, coffee grounds, and sauces. The coup de grace: Limburger cheese.

Swallowing a balut was almost a showstopper. Fertilized duck eggs are common street food throughout Asia. I thought to-be-annointed chief, a Filipino, might like it and was surprised to see him balk.

“Your career is in jeopardy,” the judge chastised, “for eating the sacred balut is integral to the process of becoming a chief.”

“If the worm won’t eat it,” someone sneered, “give it to the wasted sperm.”

The audience hooted approval.

“Come on,” I admonished, my future in the balance. “Eat the bloody thing.”

He shook his head, then toppled over. He was really drunk, the court was really drunk, most of the audience was really drunk, and I was really drunk.

“Shoot, give me the damn egg,” I said.

“Ensign, hold your nose,” Master Chief S— advised.

“Wow, I see what you mean,” I said. “Foul fowl.” I held my nose and gulped down the balut.

The last opportunity to excel was “lock and load.” Its significance was, “humility, a cornerstone to leadership,” or maybe, “trust the chiefs.”

A new chief petty officer receives his anchor during a 1980s initiation ceremony. Photo courtesy of the author.

The petty officer knelt on the floor, grass skirt parted, pink ruffly shorts pulled down, while a chief put a raw egg between his ass cheeks, then spanked it.

More eggs followed.

Another chief swabbed the yellow gooeyness. Amid the laughter were shouts that I, too, should be “locked and loaded.”

Master Chief S— would have none of that and demanded quiet. Puzzled by not seeing me, he said, “Ensign Van, front and center.”

His smile reassured me as I emerged from under the tables.

“Ensign Van,” he said, “get ready for something few people—especially officers—experience.”

Boats called everyone to attention.

Master Chief S— removed his collar device and pinned it on my collar.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

“I hereby declare you, Ensign Van, an honorary chief,” he said to raucous applause. “Wherever you are in the world, from this time forward, you’re welcome in the chiefs’ community. That includes our gatherings, and very importantly, any and all goat lockers.”

My most treasured military memento is in a cheap five-by-seven black frame. That letter authorizing me as defense counsel has been smoothed out, but the telltale wrinkles remain. The paper has yellowed. The print has faded.

However, the gold anchor pinned to it, with a star on both sides of its eye, still shines brightly.

Comments are closed.