The Life and Death of the ‘Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China’ – Part Three

The Life and Death of the ‘Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China’ – Part Three

By Olivia Cheng, Siaw Hew Wah, translated by China Change, August 6, 2022

(Continued from Part One, Part Two)

Candle lights have carried on the memory

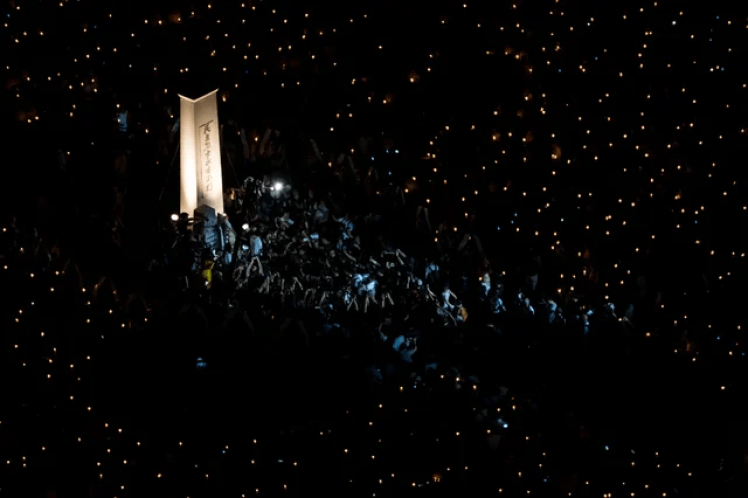

For the first time, candle lights lit up the faces of 150,000 Hong Kongers.

“Looking down the field from the stage, it was a sea of candle lights, like all the stars had fallen on the ground. The flame of each candle seemed to symbolize a solid teardrop; I had never seen a more solemn and moving scene before,” Szeto Wah (司徒華), the late chairman of the Alliance, remembered in one episode of The Common Sense (鏗鏘集, now known in English as the Hong Kong Connection). Ever since, each year and each June, as pictures of the candle vigil dominated the papers, Hongkongers have seared their candle tears in memories.

The candle tears have coursed for 30 years until last year when there was no more Letter of No Objection (集會不反對通知書) from the police.

In 2010, professors Joseph Chan Man (陳轁文) and Lee Lap Fung (李立峯), of the the CUHK School of Journalism and Communication, published a paper titled “The Mystery of Why Hong Kong Refuses to Forget the June 4 Massacre” (《香港不能忘記六四之謎》). In it, they suggest that the collective memory of June 4 has lived on in the city because of the attention it was afforded by the media at the time, and also because of the social and political environment in the years since. NGOs and media outlets had significant freedom of operation, providing ample opportunities for people to make themselves heard.

“Only when an event touches the core values of a society and the event itself stirs the hearts, does the shared experience become unforgettable enough to become a lasting memory of the society…… The guardians of memory must understand the impact of these emotional elements on the community in order to effectively mobilize people and keep the past events alive,” the authors wrote.

The uniqueness of the Alliance, and its sole task, is to preserve the memory of the June 4th democracy movement and resist its slipping out of public awareness.

This year [2021], Hong Kong authorities decided they would no longer tolerate public candlelight vigil for Tiananmen. At the same time, according to a survey by Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, the proportion of respondents “supporting redress of June 4” came in at just 45 percent, the lowest since 2003, while 28 percent believed that the Alliance should be disbanded — the highest percentage since 1993. Speaking with the media, Secretary Richard Tsoi Yiu Cheong (蔡耀昌) said that with the Alliance under pressure, it will improvise according to the circumstances but not let itself go to pieces.

So, how has the Alliance guarded this collective memory for the last 30 years? As the red line shifted, how have the members of the Standing Committee and the Alliance volunteers kept going in the face of challenges?

Walking in Victoria Park, Standing Committee member Wong Chi-keung (黃志強), now in his fifties, pulled out a “volunteers of the Alliance” T-shirt from 1993. He described the setup of the annual candle vigil. He was 24 years old in 1989, a machine operator on construction sites. Every weekend, or weekday evenings, he would go to a march or a rally without fail. He has been a volunteer for the Alliance ever since 1990, and he’s been the contact person for volunteers in the Alliance’s Organization Department.

The stage was set at the end of Victoria Park near Tin Hau station (天后站). From there he counted the soccer fields. In the second field would hang a banner depicting Tiananmen Square, so massive that it required metal supports and two dozen people in addition, it had to be wind- and rain-resistant. It took an hour to set up on the third soccer field a wooden monument for “democracy martyrs” that would then be transported to the stage with a boom truck for the laying of the wreath ceremony. The fourth soccer field was for displaying the Goddess of Democracy sculpture. Preparation normally lasted from around 7 p.m. on June 3 to midnight, sometimes to 3 a.m. And most of the volunteers would take job leave in order to work on the June 4 event.

He couldn’t tell which year he worked the hardest. “It’s hard work each and every year, not a year was idle except last year [2020],” he laughed heartily. He finally had to stop when the June 4 vigil was denied its usual Letter of No Objection.

In the early years when the passion during the Tiananmen movement cooled down, the Alliance moved its focus on preserving the memories of 1989. Even though they would be criticized as “merely repeating a ritual” (行禮如儀), all beginnings are new, and many of the ideas came from Standing Committee member Tsang Kin-shing (曾健成), such as using cable ties to hang the banners, making combined metal racks for stands at the Lunar New Year Fair, the “monument for democracy martyrs,” and many more.

As a key member of the Democracy Forum, Tsang Kin-shing would often take what he had tried at the Forum and implement it in the Alliance’s activities. In December, 1989, the night when the Romanian Revolution was violently cracked down, Tsang and district councilor Wai Hing-cheung (衛慶祥) and a group of Forum folks held an impromptu gathering at Chater Garden. Out of a whim, he brought a pile of candles for commemoration. When he proposed the same idea later during a routine meeting of the Alliance’s Standing Committee, everyone was in favor. During the “1989 New Year’s Eve Democracy Rally,” everyone held a white candle; during the “1990 New Year’s Democracy March,” they sold candles, raised $180,000 HKD, and donated it to the Romanians.

Then and there, the archetypal candlelight vigil was born.

Preparation and promotion were stepped up in anticipation of the first anniversary of June 4 in 1990. In April, the Alliance held wreath dedication to the memory of the June 4th dead. In May, Tsang, recalling that the Beijing students once flew kites over the Tiananmen Square to thwart the helicopters circling above and prevent them from monitoring the students, proposed doing the same. “It happened in Tiananmen, I could mimic the same act in Hong Kong to get everyone to participate.” A few months before, the Democracy Forum already held a bicycle parade, so he proposed that the Alliance launch the “Chinese Democracy Bike Parade,” starting from Tai Wai bike trail (大圍單車公園) to the Shatin branch of Xinhua News Agency. Some three thousand people took part, including Szeto Wah.

But the candlelight vigil needed new ideas. After the June 4 Massacre, the Democracy Forum had set up a memorial tablet and altar for Hong Kongers to express condolences, and it collected about three million signatures to burn as an offering for the massacre victims. Tsang proposed to repeat this activity for the first June 4 anniversary by collecting signatures at street stands, then torch them. He made the fire tray himself.

During the 1990 Lunar New Year Fair, the Alliance set up four stands to sell democracy books and mini Democracy Goddess figurines donated by Hong Kongers. People flocked to the stands, and the Alliance raised $400,000 HKD, all in cash. Because the banks were closed for the holidays, Tsang asked his younger brother to take the big bag of cash home for safekeeping. In the first three days of the Lunar New Year, his brother watched the bag and dared not to leave for a moment. On the fourth day, he complained about the burden, and the Standing Committee members made an urgent request to the bank and deposited the cash at night time.

For the next Lunar New Year Fair, the Alliance had nothing left to sell. As the Standing Committee members scratched their heads, Tsang proposed to Szeto Wah, “Uncle Wah, this time around, we’ll have to get you to work.” “What are we selling?” Szeto Wah asked. “Your calligraphy, that’s it,” said Tsang, “we’ll sell your calligraphies of classic poems, and it will work.” Everyone was in favor again. At Victoria Park, Szeto Wah flexed his writing brush. Each couplet sold for over $1,000 HKD to people in long queues. Unlike rice paper, the red paper for couplets does not absorb ink that well. While Tsang served Uncle Wah with ink, several volunteers blew the newly-inked couplets dry with hair dryers. Also at the scene were cartoonists Zunzi (尊子), or Wong Kei-kwan (黃紀鈞), and Malone Yuen (馬龍), who sold cartoons drawn on the spot. Thereafter, Szeto Wah, setting a trend among political figures, sold his calligraphy each year to raise funds for the Alliance until his death in 2011.

This year [2021], the Alliance’s stands at the Lunar New Year Fair at Victoria Park were banned; for the June 4 rally the police had issued a Letter of Objection. Of the series of commemoration events that the Alliance had kept for years, only Washing the Pillar of Shame and the “Remembering June 4” long-distance run, both in May, could be carried out given the SAR authorities’ ban on public gatherings of more than four people (issued in March 2021 as a COVID-19 pandemic measure).

At South Pavilion Plaza of Victoria Park on May 16, Secretary Tsoi Yiu Cheong, vice-chair Chow Hang-tung (鄒幸彤), and two other Alliance members unfurled a banner “Candlelight Everywhere to Remember June 4” and shouted “we are closer and closer to redressing June 4th!” The four set out their run from Causeway Bay (銅鑼灣), to Central Government Offices at Tim Mei Ave, Admiralty, where they were driven away by security guards, to the Pillar of Shame at Hong Kong University, ended at the Liaison Office of the PRC central government in Sai Ying Pun (西營盤). A crowd of media followed along the way, so did what looked like plainclothes police. The peace that had surrounded the annual memorial rituals was gone, and in its place was a feeling of unsettling malice.

The volunteers: the behind-the-scene heroes who come and go without a trace

Tang Ngok-kwan (鄧岳君), a current Standing Committee member, first proposed the run in 2006. Approaching the 17th anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre with the Beijing Olympics on the horizon, the number of participants in candlelight vigil had been falling. Tang, a volunteer at the time, introduced the idea of a long distance run of 17 kilometers. “We’ve held the candlelight vigil year in and year out, there seems to be no end of the tunnel. A long run on the other hand represents a spirit, that is, you have a goal and a destination.”

For all these years, the Alliance has relied on a group of volunteers who dedicate their time and efforts to a marathon in the dark, a race for which no finish line is in sight.

In The River of No Return, Szeto Wah wrote that the Alliance’s Volunteer Group (義工組) are ”the heroes behind the scene“ who “come and go without a trace” (“來無蹤去無影”). These six characters have forever stayed with Wong Chi-keung (黃志強).

Before the Volunteer Group was formed, the Alliance had had to borrow hands from other organizations, especially from the 600-strong Democracy Forum, to carry out its activities. In September 1989, after the rally to mourn the June 4 dead on the hundredth day after the massacre, Tsang Kin-shing proposed that the Alliance recruit its own volunteers. To keep the volunteers engaged, there had to be frequent activities, and he came up with the idea of writing cards to political prisoners in Qincheng Prison in Beijing on various holidays. The project, known as “Send Love to Qincheng,” started on Christmas.

Over the first 10 years, the Alliance was extremely busy. In the pre-internet era, the Anti-media Censorship Department mailed tens of thousands of newspaper clips about the democracy movement to mainland China each year. Volunteers collected articles and gave them to the Secretariat to print and then put in envelopes and stamp them. Wreath-laying on the Qingming Festival [April 5] aside, during the promotion period leading up to each anniversary, volunteers hanged banners and posters on streets for each event, big and small; in all of Hong Kong’s hundred or so parks, they toured “Chinese Democracy Movement Exhibition” working together with local groups; and on each weekend, they held “Democracy Education Theater.” At busiest times, Wong Chi-keung only slept four hours a day, meeting with volunteers more frequently than his family. “If a volunteer was getting married and didn’t invite fellow Alliance volunteers to the wedding,” he laughed, “he or she was going to be reproved.”

“When the Alliance needed hands, this group of people would come together instantly, and then disappear into the thin air once the job was done.”

On January 17, 2005, the news came that former CCP General Secretary Zhao Ziyang (趙紫陽, the reformist leader who was ousted amid the events of 1989) died. At noon the Alliance’s standing committee decided to hold a memorial. By 3:30 p.m., a group of volunteers were already hard at work setting up a temporary altar at the South Pavilion Plaza of Victoria Park for Hongkongers to lay flowers during the memorial scheduled 48 hours later.

“Those who worked for the Alliance could be any ordinary person,” said Wong Chi-keung. “The chores can be as small as folding the paper cups to hold the candlelights, but without their persistence year-in and year-out, the Alliance could not have done so many things.” As a Standing Committee member, Wong felt that there was no true hierarchy: the only difference between himself and a volunteer was that he attended a few more meetings.

“When Mr. Szeto Wah was still alive, he too was a volunteer.” He’d always appear on the scene when volunteers prepared for an event. When the Pillar of Shame, seven meters tall and weighed two tons, was erected at Hong Kong University, volunteers worked on scaffolds from noon to 6 a.m. the next day. All the time, Szeto was there. He also ordered that large-scale events must be covered by insurance. This left a deep impression on Wong.

Of the veteran volunteers who joined the work of the Alliance in 1989, there are only about a dozen of them left. Having gone through the years together, they’ve become brothers and sisters, and they are convinced that the Tiananmen massacre will eventually be redressed.

In the past, on at least two occasions, hospitalized veteran volunteers asked doctors to discharge them so they could attend the June 4 rally. Driving instructor Wong Ching Wo (黃清和) became a volunteer as early as when Concert for Democracy in China was held in May 1989. Before he died of bone cancer, he had wanted to take part in the annual May 26 Patriotic Democracy March (526愛國民主大遊行). So Wong Chi-keung sent someone to drive the wheelchaired invalid to the start point where he was greeted and thanked by fellow volunteers. When a volunteer died, fellow volunteers helped not only with the funeral but also donated to the hardup family to cover expenses.

At its peak, the Alliance had over 400 registered volunteers. After the 18th anniversary, the number dropped to 260 with some 20 of those being essential personnel. For the last few years, Wong Chi-keung has been putting his efforts into training lead pickets, but he’s never been concerned about not having enough volunteers. “It’s been my belief that, if needed, enough people, enough to fill one of the six soccer fields at Victoria Park, will stand up and volunteer for me. I have no doubts about this.”

“It’s so precious to have these brothers in arms bound together for decades. You can goof together with a bunch of friends for twenty years, but a group of people who’ve come together with shared beliefs, who’ve fought shoulder to shoulder with you, for twenty and thirty years is something else. ….It’s not easy to have a group of people like this out of the multitudes of millions.” He mourned for the passage of some of his comrades, but feels fortunate that they’ve met.

The story of the volunteers has also become part of the collective memory kept alive by the Alliance.

How to pass the torch to the next generation

When Leung Kam-wai (梁錦威) was in high school, his history textbook contained just one short paragraph about the Tiananmen protests and massacre, and nothing at all about the democracy movement in Hong Kong. Only much later would he come to learn that the beginnings of the democratic movement in Hong Kong originated in the city’s support for the 1989 student movement in Beijing.

At the heart of the Alliance’s generational gap is the [lack of] shared memory. Leung was four years old in 1989, and all he remembers about that year was his parents crying in front of the TV during a broadcast covering news of the massacre. He didn’t learn any more about it until in high school when a teacher brought up the topic. From then on, he grew more interested, reading newspaper clips and related books, and participating in the vigils. In college, he joined the HKFS, and one year, he and a group of members once staged a 64-hour hunger strike on Times Square in Causeway Bay to mark the June 4 anniversary.

This happened between 2003, when Hongkongers marched on July 1 against the proposed “national security” legislation under Article 23 of the Basic Law, and 2008, when Beijing hosted the Olympics. Leung, a student of China Studies, joined a mainland-Hong Kong exchange program. He tried to mention the 1989 movement with Chinese students, and every time he did, he was asked, “How do you all know about it so well?” He said, to mainland Chinese, the June 4 massacre is a blank spot because they’ve had no access to information about the Tiananmen movement. “Because they don’t know, so they are surprised by what we know; and what we know is a blur to them.” The topic was always a non-starter.

Without the Alliance keeping the memory alive, the public would not have maintained its awareness and enthusiasm about the Tiananmen movement.

Leung said, “Case in point: many of the youngest who took part in the protests of 2019 had only a vague idea of the Umbrella Movement in 2014…, precisely because there hasn’t been an organization like the Alliance that has persisted in the same activities year after year for the society to remember. Then for young people, it quickly becomes a thing of the past.”

Starting in 2011, the Alliance arranged to have a “June 4 Stage” tour in more than twenty schools with two theaterical plays — “Placing a White Flower in Tiananmen Square” and “Let the Yellowbird Fly.” In the same year, the Alliance and the Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union (教協) jointly held “Days and Nights at the Square — Student Camp” at Victoria Park where 64 students camped for 64 hours to listen as participants of the Tiananmen movement as well as Hong Kong supporters shared their experiences from the events of 1989. But Leung pointed out, as the new Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education’s scholastic calendar was implemented and exam times shifted earlier, supporters who were teachers began to come under a lot of pressure. By 2014, the camp applicants fell precipitously to single digit, and the camp activity had to be discontinued. After the Umbrella Movement, the 64-hour camp was never revived. Lo Wai Ming (盧偉明), who is in his forties and has been a standing committee member for over a decade, said that, for young people, the camp may seem “out of touch”; moreover, they may not know that, “in 1989, students camped in Tiananmen Square and that their tents were brought to Beijing by student members of the HKFS.”

Over the years, the CCP has kept changing its characterization of June 4, and redressing the movement seems beyond reach. “We did not engage in the democracy movement for the applause of the moment; it is a prolonged struggle,” said Tsoi Yiu Cheong. Tsoi believes that the role of the Alliance in the lore of June 4 is like erecting a beacon. “If no one tells the history, it would probably have long been distorted.” For years the Alliance’s work has been criticized as “going through a ritual” (行禮如儀). Albert Ho (何俊仁) says such criticism is “absurd”: as long as the ritual is solemn and sincere, it is by itself already powerful and meaningful.

Will the abrupt imposition of the National Security Law make it impossible to keep the memory of June 4 alive? Under the NSL, teachers will not be able to discuss the Tiananmen Movement freely with students, the annual June 4th vigil could be banned indefinitely, freedom of assembly will be gone, and a generation’s political enlightenment will be lost. But Leung Kam-wai does not believe the memory of the vigils or the habit of remembering Tiananmen can be wiped out so easily; they will live on in another form, that is, on social media.

The Alliance’s Youth Group – a failed experiment to pass on the torch to the younger generation

The older Standing Committee members’ attempts to relay the baton to the next generation have always been fraught with challenges.

At the June 4 rally in 2001, the Alliance announced the establishment of an Alliance Youth Group (支青組) that would operate independently of the main organization.

Chiu Yan-loy (趙恩來), a serving Alliance Standing Committee member, was a highschooler at the time who by happenstance saw Albert Ho manning a June 4 street stall in Tsuen Wan (荃灣). He filled a form for the Alliance’s Youth Group, and then mustered the courage to sign up at the office of the Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union for a position of secretaries. Ten would be selected out of 40 candidates ranging from highschool students to 25-year-olds, including Crystal Chow (周澄) and Alvin Yeung (楊岳橋), who later studied in Beijing. Chiu served as a Youth Group’s secretary for four years. At the time, the group mainly concerned itself with either doing volunteer work for the Alliance, or activities such as reading statements, singing, or performing stage plays at the annual Tiananmen vigil. They would also hold independent events, including a youth camp, book clubs, and film screenings.

However, a former member of the Youth Group once voiced criticism that the organization had dwindled by 2007 to a few active participants, and the Alliance’s leadership was more geared toward “conserving the existing force” without long-term strategies to include and on-board young people.

By 2014, a candidate for the standing committee proposed a “one-on-one” plan to mentor young people, given the Youth Group’s serious shortage of participants. But the results were disappointing. Vice-chair Chow Hang-tung (鄒幸彤) says that the Youth Group has become “almost non-existent,” with “an irreversible trend stemming from the difficulties of recruiting youth,” except for the few young people who helped design posters.

The two generations of Standing Committee members have agreed on the five operational guidelines (五大綱領) but differed in their approaches. The Alliance maintains a Facebook page but has no Instagram account nor uses the popular meme format. Chow Hang-tung said the younger members of the Alliance once proposed memes to juxtapose the Tiananmen scenes in 1989 with today’s situation, but the older generation, being more conservative, effectively vetoed the idea.

In 2016, amid criticism that the vigils have been little more than “keeping up a ritual,” the HKFS withdrew from the Alliance. But the Alliance has not always rejected new ideas. Chow Hang-tung tried, for example, a 1989 Guided Tour led by Chan King-fai (陳景輝) to retrace the footprints of Hongkongers supporting the democracy movement in 1989; after four activists in Chengdu were charged and sentenced to three and half years in prison for selling home-brewed “Remembering 8964” wine, the Alliance worked with Mobile Co-Learning (流動共學) to distribute June 4 beer and hold democracy salon discussions. To these new endeavors, the older standing committee members adopted a “do as you please” approach.

Virtually no Alliance members have birthdays after 1990. Lo Wai Ming, born in the 1970s, recalled that, when he was the president of the student union at Lingnan University (嶺南大學) and held June 4-related activities around the year 2000, attendance was already sparse, and he was criticized as a “troublemaker.” Even back then, the HKFS was already dissatisfied with the Alliance and didn’t send candidates for several elections of the Standing Committee. Lo believed that the Alliance should have put in serious efforts to recruit new blood starting a decade ago. Now that the student organizations have withdrawn one after the other, and the space for civil organizations has narrowed in the current political environment, he thinks that parents should take up the role of passing on the memory. He himself set up a “1989@香港” Facebook page to do his part.

He lamented, “we don’t have much capacity to do this anymore – we are running out of time.”

(To be continued)

The Life and Death of the ‘Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China’ – Part One, by Olivia Cheng, Siaw Hew Wah, translated by China Change, July 29, 2022

The Life and Death of the ‘Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China’ – Part Two, by Olivia Cheng, Siaw Hew Wah, translated by China Change, July 31, 2022

Comments are closed.