The Life and Death of the ‘Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China’ – Part Five

The Life and Death of the ‘Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China’ – Part Five

By Olivia Cheng, Siaw Hew Wah, translated by China Change, August 15, 2022

(Continued from Part One, Part Two, Part Three, and Part Four)

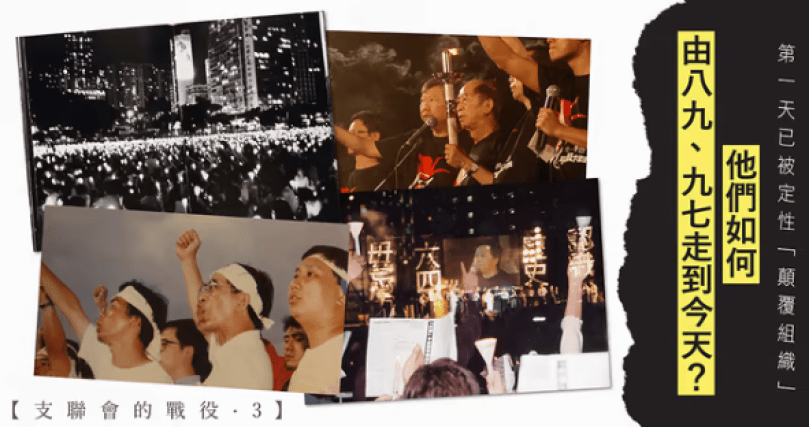

At the 1996 Vigil at Victoria Park, a gigantic banner fluttered in the wind on the backdrop of the stage: “Crossing Past 1997.” Before it on the stage stood a row of people holding up candlelight. Among them a man with a white headband read a tribute with a loudspeaker:

“To the compatriots who died during the 1989 democracy movement: in 391 days, Hong Kong will be turned over to China. The troops that killed you will march on the streets here; the tanks that crushed your flesh will roar into Hong Kong; the machine guns that left your bodies peppered with bullet holes will take aim at our chests. But let us tell you this: we are composed; we are ready for the challenge we face without fear.”

The lens of the live streaming cameras focused on that unperturbed face. He was Szeto Wah (司徒華), then-president of the Alliance. He once thought the 1996 vigil would be the last one, as “following the turnover, the Alliance will become the first target of crackdown and persecution.”

“Szeto Wah prepared for the worst, and harbored no illusion for the 1997 handover,” recalled Mak Hoi-wah (麥海華). “We decided that we were not going to back off, we were against retreat, and we were going to carry on for as long as we could.” At the time, Mak said, the standing committee members were bracing themselves for the possibility that they would be arrested and the Alliance outlawed.

In the few years following the handover, from 1997 to 1999 and onwards, Hongkongers were anxious. But the marches, assemblies, and vigils organized by the Alliance were held without incident.

Come 2020, the situation has seen a sharp change for the worse. Those who still chose to take part in the election of the Standing Committee told reporters that they were prepared to be arrested and the Alliance shut down for good. They knew all along that their battle has been and will be a long one.

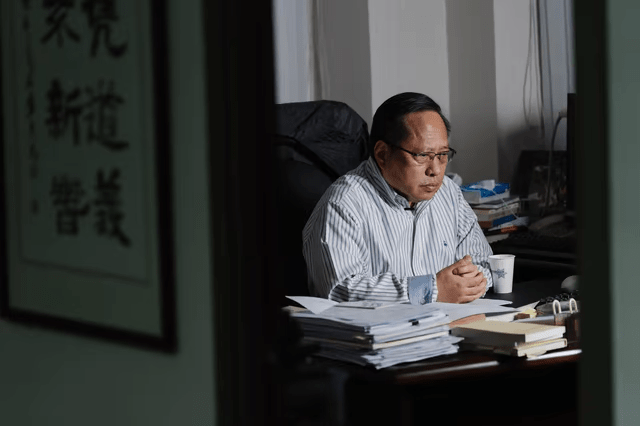

As the history of Tiananmen is twisted further, it’s incumbent upon us to carry on the memory: Albert Ho

“Do you know how many times Beijing has changed the definition of the Tiananmen Movement?” Albert Ho (何俊仁), the vice-chair of the Alliance, posed the rhetorical question when speaking with reporters during the washing of the Pillar of Shame at Hong Kong University on May 2 [2021]. Quoting from the state-published The Communist Party of China: A Concise History (《中國共產黨簡史》) last updated this February, he said: “Relying on the people, [the Party] opposed the turmoil unequivocally, and took decisive measures on June 4th and squashed the counter-revolutionary riot in Beijing area.”

He said, In 1989 and immediately afterward, Beijing defined the movement as “turmoil” (動亂) “insurrection” (叛亂) and “counter-revolutionary” (反革命叛亂) in turn, later it referred to it as “the political turmoil in late spring and early summer” (春夏之交的政治風波) “June 4th incident” (六四事件), and the latest iteration is “counter-revolutionary turmoil” (反革命動亂).

“Deng Xiaoping, who was the de facto supreme leader of the CCP at the time and directed the troop’s crackdown, wanted to downplay the June 4th event,” said Ho. “People in Beijing said, the CCP claimed that the guns were for fighting enemies and killing students would not end well. In the past Beijing had never been ravaged by wars, even during the Beiping-Tianjin Campaign [of the Chinese Civil War], troops didn’t march into the city [and fight battles there]. But in 1989, the military opened fire on ordinary people, and Deng Xiaoping said the CCP must protect its hold on power even if it had to kill 200,000. So he knew it was a disgrace.”

“Later on, he wanted to restore hearts and minds. Though some were imprisoned, like Wang Dan (王丹) and Wang Juntao (王軍濤), they were given lighter sentences when compared to Liu Xiaobo (劉曉波) or Ilham Tohti (伊力哈木), who were sentenced life in prison. As China accelerated its Reform and Opening Up, the CCP defined the 1989 movement as the ‘1989 Incident’, or ‘1989 disturbance.’”

Albert Ho believes that the CCP regime, celebrating its 100 anniversary of founding, wishes to whitewash history when it recently brought back the term “counter-revolutionary riot” to characterize the 1989 movement. “It was a massacre, as a matter of fact,” he said. The gunfire that night has become a permanent nightmare, and he believes those who stay quiet about it help erase this part of history.

“Our responsibility,” Ho said, “is to make sure people remember it.” According to Ho, in earlier years, the democrats in the Legislature Council could submit motions to redress the Tiananmen massacre; during the debates, councilors from the DBA (民建聯, Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong) were always silent, unresponsive to the emotional addresses by the democrats and voting “nay” in the end. Among them, “perhaps James Tien Pei-chun (田北俊) would say a few words in defense of June 4th crackdown, claiming it secured China’s stability, prosperity, and development over twenty years. But it doesn’t make any sense. The [SAR] government, the DBA, the HKFTU (工聯會, Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions), none of them dared to respond, because they know very well that it is a thorn.”

“The 1989 movement can be debated but not forgotten,” said Ho.

From its founding, the Alliance was identified as a ‘subversive, anti-CCP’ organization

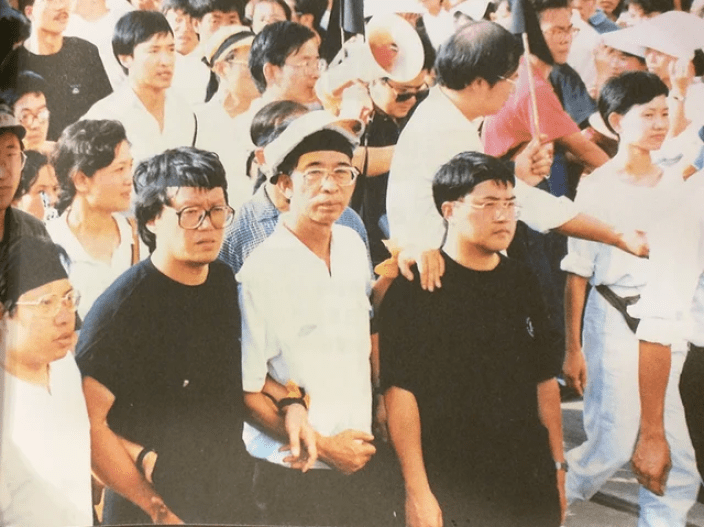

It was not without reason that the Alliance had prepared for the worst before the 1997 handover for its mission to resist the communist regime and refuse to forget. As Szeto Wah wrote in his memoir The River of No Return, “the Beijing regime had used all sorts of methods to pressure the Alliance since its founding.”

Within a month of its founding, state media descended on the Alliance: On June 12, 1989, then-director of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office of the State Council Ji Pengfei (姬鵬飛) warned Hongkongers not to interfere with the internal affairs of the mainland in a speech – “[we] will not allow someone to use Hong Kong and Macao as bases to subvert the Central People’s Government.” On July 21 of same year, the People’s Daily published an article by “Ai Zhong” (艾中) titled “No Tolerance for Sabotaging One Country Two Systems,” which labeled the Alliance as the subversive organization that was turning Hong Kong as a base to subvert the central [Chinese authorities]. In August, when meeting with British Foreign Secretary John Major in Paris, Chinese Foreign Minister Qian Qichen (錢其琛) stated that “the Chinese Foreign Ministry will raise concerns with the U.K. that some people and organizations are working on turning Hong Kong into an anti-CCP base.”

On October 1 the same year, Baixing Biweekly (《百姓半月刊》) reported that Xu Jiatun (許家屯), director of the Hong Kong branch of the Xinhua News Agency at the time, met with Szeto Wah. Xu told Szeto that the transitional period in Hong Kong was sensitive and vulnerable, and that were China-U.K. relations to deteriorate, the “one country, two systems” deal may not be realized. As such, Xu attempted to persuade Szeto to disband the Alliance, which the mainland regime regarded as a “counter-revolutionary” organization.

In the same month, Vincent Lo Hong-shui (羅康瑞), a member of the Basic Law Consultative Committee, also publicly called on the Alliance to disband, arguing that the Alliance was designated as a “counter-revolutionary organization” on the one hand and, on the other, the Chinese democracy movement that the Alliance supported existed no more. Lo stressed that doing so was not to placate China, but make a proactive move to improve Hong Kong’s relationship with Beijing.

Also in October, Szeto Wah and Martin Lee (李柱銘), chair and vice-chair of the Alliance respectively at the time, were kicked out of the Drafting Committee for the Hong Kong SAR’s Basic Law.

In February 1990, the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office of the State Council summoned officials at the British embassy in Beijing and read them an official document. It wasn’t until 2019 when researchers with Decoding Hong Kong’s History (香港前途研究計劃) discovered this document as they explored declassified archives in London. The Hong Kong and Macau Affairs officials in Beijing told their British interlocutors back in 1990 that the Alliance was a subversive organization that was planning on launching a series of “anti-Chinese activities,” and that the events the Alliance was going to carry out between April and June that year to mark the first anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre all aimed at subverting the Chinese government and China’s socialist system.

Even the British Hong Kong government opposed the Alliance. After the first June 4th anniversary, per Governor David Clive Wilson’s request, the Senior Member of the legislature Allen Lee Peng-fei (李鵬飛) met with Szeto Wah demanding him to shut down the Alliance so as to avoid inconvenience for the China-U.K. relationship.

Of course, Szeto Wah ignored them all.

Registered as company to operate legally under ‘One Country Two Systems’

Faced with threats and criticism, the then-chair of the Alliance Szeto Wah told the Liberation Magazine (解放月刊, later become the Open Magazine 開放雜誌) in November 1989 that, there were two scenarios in which the Alliance would be disbanded — if it was to be indicted and outlawed by the British Hong Kong government for illegal activities, or if the Alliance itself decided to do so. “Some people think the Alliance should disband in order to accommodate the larger picture of mainland-Hong Kong relations. Now, how many times are we going to give in when the CCP is talking tough on something else the next time around? And the next?” he questioned.

Martin Lee, who was vice-chair at the time, also weighed in. “The Chinese leaders must understand this is what one country, two systems means. The ‘evidence’ for subversion as alleged by some is really just the Alliance exercising its freedom of speech. Even after 1997, the Alliance’s existence or dissolution will be governed by Hong Kong law. The Alliance is not challenging anyone; everything it does is within the law, it’s just not to China’s liking.”

The Alliance did as they planned, detail by detail. To start, it had to be registered as a company in order to acquire legal status and a management mechanism to ensure that it would not be dissolved under pressure without legal basis. It stated its mission, which was to promote democracy in China. Albert Ho, the secretary at the time, [and a solicitor,] also took charge of legal matters.

Ho remembers the preparations as though it was yesterday. He spent all his time during the last week of May 1989 contacting pro bono lawyers and discussing the bylaw. Then he visited the office of the Companies Registry (公司註冊處) and handed documentation to its chief. When learned that the Alliance would raise funds from the public, the chief asked them to include certain important clauses in the bylaw. Because it would take time to go through administrative procedures, Ho applied for a temporary commercial registration under the name “Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China.” Then he hopped to the Inland Revenue Department (税务局) and the bank to set things up.

“The bank opened an account for us and we deposited the donations we had received – thanks to this account, we raised over 20 million HKD during the Concert for Democracy in China (民主歌聲獻中華) on May 27, an unbelievable amount. I worked well over ten hours every day, attending meetings, marching on the streets, and managing the office work. I knew from the start that it was a sensitive company, and I went on being the secretary signing more documents.”

Apart from responding to external pressure, the Alliance also had to promptly handle crises caused by differences among fellow travelers on how to resist. A few days after the Tiananmen massacre, someone proposed a bank run on China’s state-run banks in Hong Kong. Others even advocated buying guns and ammunition to fight a revolution. The Alliance began to worry about the unexpected. “Over those few days, the Hong Kong government told me that Beijing had sent many people, all single men, who had checked into hotels,” Albert Ho recalled. “We feared there would be violence.”

Mak Hoi-wah also remembered those few days. “We initially planned on carrying out the ‘Three Strikes’ [on June 7] — a labor strike, market strike, and academic strike, but the night before a riot broke out at Mong Kok (also known as Pitt Street Incident). A high level government official told Uncle Wah that, ‘the situation is very dangerous; if you go on [with the Three Strikes] as planned, you will be blamed if something goes wrong.’ So we decided to cancel the ‘Three Strikes’ and work on defining clear goals so that everyone has a guideline to prevent the movement from veering astray.”

What emerged were the “Five Operational Guidelines” (五大綱領) that have been carried on until today [as of the time of this article’s publication in early June, 2021].

Over the years, the “Five Operational Guidelines” has been a subject of controversy, and more recently a target of attack by the pro-establishment camp under the new National Security Law. But ironically, the strategy was born in 1989 out of the need to preserve the organization from the threat of being shut down.

Anchored on Five Guidelines, the Alliance begins discreetly supporting the mainland democracy movement

The “Five Operational Guidelines” — release democracy activists, redress the June 4th Massacre, hold those who committed the massacre accountable, end one-party dictatorship, and build a democratic China — first appeared on record at the first June 4th anniversary vigil in 1990. In the candlelight vigil next year, they were referred to as “Five Goals.” Exactly when were they formulated? Thirty-two years on, most of the Standing Committee members interviewed couldn’t quite recall.

Stand News, assisted by clerks at the Alliance, looked up the meeting minutes of the Standing Committee during 1989-1991, but didn’t find the “Five Operational Guidelines” in the agendas. What we found was that, in January 1990 when discussing the organization’s future direction, the Committee members agreed on “five goals,” or “the current direction” as a result of their deliberations on the Alliance’s strategy at the time. It wasn’t until August 1990, the phrase “Five Operational Guidelines” appeared for the first time in the election platforms of candidates Lee Cheuk-yan (李卓人) and Mak Hoi-wah (麥海華) during the election of a new Standing Committee.

Albert Ho explained: the conception of the Five Operational Guideline had its internal logic. “Redressing 1989 democracy movement, holding those who were responsible for massacring protesters accountable politically and legally, and releasing democracy activists” are a trinity; ending one-party rule and building a democratic China is the long-term goal, not something we expected to happen overnight. And we’ve never advocated constitutional change through violence.”

Of the five guidelines, “end one-party dictatorship” is the most controversial under the new National Security Law. Members of the standing committee pointed out that it was originally a banner displayed in an assembly of the “April Fifth Action” (四五行动) in 1989. On May 14 that year, the April Fifth Action held a sit-in protest at the Star Ferry Pier (天星碼頭) to support Beijing students who had staged a hunger strike demanding to have a dialogue with the government. The assembly issued a statement calling for “ending one-party dictatorship in China, holding true democratic elections, freedom of expression and assembly, and releasing political prisoners.”

Albert Ho elaborated: The CCP claims that its government is a multi-party cooperation but in reality is more of a dictatorship, and by “ending one-party dictatorship,” the Alliance recommends that the CCP wins power through elections.

The Five Operational Guidelines aside, the Alliance also stressed “peaceful, rational, and non-violent” action from very early on in the movement. Drafting a declaration for the New Year Eve rally at the end of 1989, then vice-chair Cheung Man-kwong (張文光) wrote, “through peaceful, rational, and non-violent means, [the Alliance] advocates for the step-down of the fascist regime via procedures of democracy and the rule of law.” But this sentence was taken out of the rally’s published pamphlet. Richard Tsoi (蔡耀昌), quoted various then-Standing Committee members as remembering that at many rallies and parades, Szeto Wah would call upon the crowds to behave according to the peaceful-rational-nonviolent slogan. He’d also warn those participating in the parades to “be alert for provocations” if he saw people carrying water balloons.

The standing committee’s meeting minutes in January 1990 contain the following text (excerpt):

The Situation:

– Democratic reforms in the Eastern European bloc have laid to rest the myth that Communist regimes are invincible. This is a morale boost for the organizers.

– China is becoming more isolated as Eastern European countries democratize, resulting in it moving to a more reactionary direction and tightening its control over Hong Kong.

– China and Britain still hope to maintain a friendly relationship in light of their interests in the post-97 handover era.

– The pro-democracy forces are growing stronger; as a result of supporting the Alliance’s activities, some Hongkongers will dedicate themselves to the promotion of local democratic causes.

Guidelines and Strategies:

– As a long-term support movement, the Alliance will adopt a multi-centric and multi-pronged strategy, hosting a variety of large and small activities in diverse formats.

– Continue to uphold the peaceful-rational-nonviolent principle, choosing peaceful transformation over violently overthrowing the tyrannical regime.

– Focus our slogans on “down with Deng Xiaoping, Li Peng (李鵬), and Yang Shangkun (楊尚昆)” as well as “end one-party dictatorship.”

– Our position is that of planting our feet in Hong Kong, with eyes on China, through a global perspective. Depending on what the circumstances call for, we will undertake activities that are either slow but persistent over time, or actions that are rapid and marshall overwhelming force.

The Five Operational Guidelines have been not only the Alliance’s strategy to prevent its dissolution, but also its roadmap for continuing social movements by supporting democracy movements in a persistent manner. What is criticized as “going through a ritual” is in keeping with the principle of diversity that was decided upon decades ago.

Among its other endeavors, the Alliance also assisted mainland democracy activists in exile. Due to the risks and sensitivity involved, such work was handled discreetly by the Human Rights and Aid Department, which was in the early years led by Standing Committee members Pastor Chu Yiu-ming (朱耀明牧師) and Yeung Sum (楊森). The Alliance did not publicly state that it had participated in the “Operation Yellowbird,” but its annual reports included the line “assisting democracy activists to seek legal political asylum during their stay in Hong Kong.”

Albert Ho didn’t elaborate on the Alliance’s assistance to exiled democracy activists in the years following the June 4th massacre. “Operation Yellowbird was part of the democracy movement, but the Alliance’s work was in Hong Kong, we were limited by the fact that we didn’t have an [underground] network [to smuggle people out of China].” Richard Tsoi recalled, when asked about details on Operation Yellowbird by a reporter, Szeto Wah didn’t answer. When the reporter pressed him, saying that many people wanted to know, Szeto merely answered, “You’re not just a reporter, but a human being as well.”

(Editor’s note: Szeto was urging the journalist to “be a decent person” and avoid digging for information that could inconvenience or endanger those involved in Operation Yellowbird.)

But in his memoir Humble Struggle (《謙卑的奮鬥》), Albert Ho offered more details. “After democracy activists sneaked into Hong Kong, the Alliance provided assistance and care, arranging them to stay in San Uk Lang (新屋嶺) in the New Territories. Then we did thorough research to ascertain their political asylum seekers status. In addition to settling them in safe places, the Alliance asked foreign consulates in Hong Kong to accept them into their countries. In the end, all consulates helped. The United States chose the more famous ones, while the French consulate accepted everyone regardless of their status and background.”

The Human Rights and Aid Department became the Rights Defense Department. In recent years, led by Richard Tsoi, Lee Cheuk-yan (李卓人), Albert Ho, and Chow Hang-tung (鄒幸彤), it has concerned itself with imprisoned mainland dissidents and rights defenders, such as mainlanders arrested for voicing support for the Umbrella Movement in 2014, and human rights lawyers detained during the 709 crackdown in 2015. It also advocated abolishing the crime of “inciting subversion of state power” and the use of torture. The Department’s work reports on its UN advocacy work and Facebook campaigns are long, but descriptions on assistance to mainland prisoners of conscience are brief. “We have to put their safety first — it’s humanitarian support and I can’t elaborate,” Albert Ho said.

(To be continued)

The Life and Death of the ‘Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China’ – Part One, by Olivia Cheng, Siaw Hew Wah, translated by China Change, July 29, 2022

The Life and Death of the ‘Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China’ – Part Two, by Olivia Cheng, Siaw Hew Wah, translated by China Change, July 31, 2022

The Life and Death of the ‘Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China’ – Part Three, by Olivia Cheng, Siaw Hew Wah, translated by China Change, August 6, 2022.

The Life and Death of the ‘Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China’ – Part Four, by Olivia Cheng, Siaw Hew Wah, translated by China Change, August 8, 2022.

Comments are closed.