I See My Life in Music, So I Used It to Find My Freedom and Peace After Years of War

I sat alone and confined in a stress position for hours and was running out of Schlitz for the exercise. The only thing that kept me from jacking it in was the intolerable shame of quitting. I figured this would be hard, which implies that I figured something out like an equation. In the case of this field problem, however, two plus two equaled bananas. I couldn’t figure out how this wasn’t impossible.

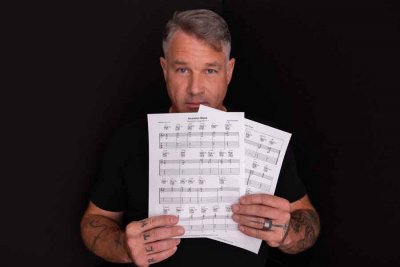

Derek Nadalini played guitar as a hobby for years before handing himself over to the Global War on Terror. Photo courtesy of the author.

While working through the calculus of this devolving snipe hunt, I tried to manage the weight of my gear as it hung from my shoulders and became increasingly difficult to hold. I continued the mission because the Ranger creed says, in part, “I accept the fact that as a Ranger, my country expects me to move further, faster, and fight harder than any other soldier.” That social contract is possible because there are two kinds of Rangers: hard Rangers and smart Rangers. I made a career out of switching between those two problem-solving approaches, but my kind defaults to the former when problems become intractable. It works, especially when we’re together, and it’s why Rangers ultimately prevail. Their collective will makes them unbeatable. You can hurt them, maybe kill a few, but Rangers will never lose. Good luck to adversity in its relentless attempts to have a go at us.

But I was operating as a singleton in this case. I wouldn’t get help from my tribe until I linked up with them later in the week. It was three in the morning. I was entirely alone, and despite a long career of looking adversity in the eye and daring it to stop me from meeting the mission, I wasn’t sure I could pull it off this time.

Things had changed after a 2006 mission known as Objective Hadley. By then, I had left the Ranger Regiment, and I had been a Delta operator for two years when the adversary tricked us into clearing a building with explosive artillery rounds in the floor. Each round had a lethal radius of nearly 500 feet and a casualty radius of nearly 1,000 feet. We found it within seconds of making entry. We had just enough time to evacuate the building before the explosion but not enough time to reach the minimum safe distance for an IED of that size.

I learned a lot about myself in the few seconds before and after detonation. As I made my way to the rally point, the prospect of dying didn’t bother me. I was entirely free of fear. I would conduct myself with dignity, come what may, because we fight for each other at times like this. Still, I was thoroughly pissed as the bomb went off. We’d put ourselves in a position to lose.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

When the overpressure caught up with me, it felt like a four-by-eight-foot sheet of plywood passed through my body. It transported me to another plane, a place where everything moved at a strange pace. The world became muffled, nauseating, and awash in a viscous medium. I had a sense of being in a private place, in suspended animation that tempted me to give in and just float away. But I knew that I had to regain my senses and prepare to seize the initiative. My mates got hit too, and IEDs often preceded complex attacks. I pulled hard at the memory of reality to escape that punch-drunk trance so I could find my guys, render aid, and fight.

Music school, and one exercise in particular, taught Derek Nadalini that the art form thrives within a supportive community. Photo courtesy of the the author.

God, I wanted to fight.

Over the years, that desire to fight only grew more intense, so I’d stayed with the war for as long as I could. Before my retirement from the unit, four more blasts hit me as hard as Hadley. My physical and mental health declined steadily. I did not understand the source of the problem until doctors at Walter Reed diagnosed me with Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) in 2016. Although the kind people in Bethesda had a name for my deteriorating health, they offered no user manual for a damaged brain. Our society isn’t built to carry on its back people with brain damage. It was up to me to figure myself out. I was responsible for my own outcomes.

I decided it was time for a gear-grinding change of pace.

One day, while scrolling through a playlist that reminded me of things I like to remember, I realized I see my life in music. I brought home my first rock ’n’ roll record at age 11 and came of age during the Guitar Hero period. Inspired by a list of astounding artists, I played guitar by avocation for years before handing myself over to the Global War on Terror. When I tried to figure out what to do in retirement with my scratch-and-dent-sale brain, I returned to the guitar like a starving man at the Whole Foods hot bar. I wanted creative freedom based on knowledge and mastery, so I applied to music school.

I wanted to go to the Berklee College of Music, even though I believed I had absolutely no business there. I couldn’t tell admissions the difference between a bass clef or treble clef, nor could I point to a spot anywhere on the planet where they could find middle C. The only thing I didn’t suck at was an original composition from my coffee house open mic night period, which I played in the audition with enthusiasm akin to a castaway who is rescued from a deserted island. For some reason, they let me in.

When I started the program, I realized I had a tiger by the tail. The good people at Walter Reed warned me that TBI would make it impossible to overcome cognitive bandwidth limitations, no matter how hard I worked. I would have to work smarter. Over the years, I gradually figured out what that meant for me, but music school changed everything.

Derek Nadalini bought his first rock ’n’ roll record at age 11 and came of age during the Guitar Hero period. After scrolling through a playlist one day, he realized he sees his life in music. Photo courtesy of the author.

That’s why I sat, confined alone in a stress position at three in the morning, doing an exercise called the Inversion Blues for my Chords 201 class. The gear strapped to my shoulders wasn’t a rucksack or a rifle this time. It was a Gibson Les Paul, known for its fantastic tone as well as grinding a player down under its weight. I’ll hold off on muso speak about chord and music theory. Simply put, that exercise took my classmates one week to complete.

It took me five.

The only thing that kept me from jacking it in by week three was the intolerable shame of quitting. After five weeks and hundreds of attempts to play the Inversion Blues, I drove my pride like I stole it, ramming into a cognitive threshold that acquainted me with the naked reality of life with brain damage. The real mistake I made in all of this had less to do with technique and more to do with going at it alone. Music doesn’t work that way. It exists and thrives within a community that supports its members—just as it did when things got real during Objective Hadley.

In the military, we worked out of team rooms, spaces where we solved tactical problems together. We emerged unbeatable because we had each other, even (or especially) when things got tough. It didn’t take me five weeks to learn a piece of music. It took me five weeks to make the connection between walking out of a Special Missions Unit team room full of commandos and into a team room full of musicians.

Music has an energetic tie that binds. That energy connects us as listeners and practitioners. Musicians connect by maintaining a connection with their forebears (like Bach, Coltrane, Hendrix, and others).

I realized I was never alone during those five weeks. Isolated, perhaps, but not alone. I stopped trying to hard-Ranger my way through the Inversion Blues. I put my guitar down, grateful for the rest, and emailed my tribe. I told them where I was having trouble by pointing to specific spots on the sheet music and explaining the physical and mental obstacles I experienced at each friction point.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

One by one, in a way that brings tears to my eyes as I write this, each musician responded with sincere interest and friendship, providing pointers and Zoom invites to play the Inversion Blues together. Through that process, they introduced me to an entirely new way of thinking, moving, and problem-solving. By the end of week five, I could finally play the song flawlessly. I became a musician rather than a casualty.

Good luck to adversity in its relentless attempts to have a go at us.

We are unbeatable.

Comments are closed.