Two Guys to a Bag, One Bag at a Time. We Each Became Experts in a Macabre Parade.

Whenever I hear the thwack-thwack-thwack of a helicopter, I stop and look up. Nothing too unusual about that, except a shot of adrenaline unfailingly accompanies these sightings. The hair on my arms and neck stands up, and something I can’t quite describe rises in my chest and gut. The feeling is fleeting, and I’ve grown adept at hiding it after all these years. I tell whoever I happen to be with what kind of helicopter hovers in the sky above us, and it ends there—unless the bird is an old Huey or Chinook.

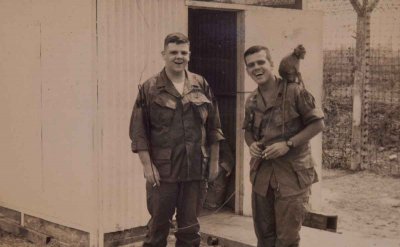

Ed Meagher arrived in Vietnam on the same day the Tet Offensive began. Photo courtesy of the author.

I arrived in Vietnam around three a.m. on January 30, 1968. It was, whether by coincidence or poor luck, the same day the Tet Offensive began. I was a radio operator and newly promoted Air Force staff sergeant assigned the six p.m. to six a.m. shift in the communication squadron. By 6:30 most mornings, my troops and I sat down to breakfast or dinner, depending on our preference, then tried to sleep in the hot, noisy barracks before getting up and doing it all again. But the war often required warm bodies for crap details like filling sandbags, riding shotgun on convoys, and any other gritty, shitty job you can imagine. That’s when a runner would wake us from our daytime slumber, and tell us where to go and when to be there. It was a royal pain in the ass, and as a noncommissioned officer, I usually had to lead them.

Some five months after arriving, a runner arrived with simple instructions: Go to the head shed, load the assembled troops into two pickups, and take them to the mortuary at Ton Son Nhut. We headed as instructed to the large aluminum Quonset hut that stood at the end of a taxiway on the north side of the runways, away from the main base. In the heat and misery, we waited, unsure about what we’d come for—in the military you get used to standing around waiting on ambiguous orders. When a fire truck showed up, the men on board seemed to know even less than we did.

Finally, tower radio traffic crackled, clearing a helicopter to cross the runway and land near the Quonset hut. We looked up to see a Chinook in the sky, thumping loudly and throwing up dirt and small rocks in every direction as it landed. Over the tower radio, we heard a request for the fire engine to move closer to the helicopter, and we waited, exhaust fumes from the JP-4 fuel mixing with the hot, humid air. The smell could overwhelm you, but I’ve always loved it.

Ed Meagher was a radio operator assigned to the communications squadron in Vietnam, where he worked the overnight shift. He and his troops were often assigned to “little details” during the day. Photo courtesy of the author.

Finally, figures emerged slowly from the Quonset hut. They came two at a time, dressed in various colored medical scrubs with hats and masks. Some wore rubber aprons and gloves. Their movements seemed meandering, unhurried. Still, I knew nothing, and the rest of my little detail knew better than to ask questions. We watched as the crew chief, fire truck driver, and helicopter crew huddled into small conferences. The folks from the Quonset hut wandered back at a pace no faster than a stroll, then reemerged with wagons and gurneys.

The crew chief in a bulbous helmet waved me over to the helicopter, and I bent beneath the blades even though they loomed some 20 feet above us. The roar grew louder, and the crew chief screamed in my ear—something to do with my men and what was on the helicopter. I raised my palms as if to ask, “What did you say?” His face registered disgust, and he grabbed my arm and led me to the large rear door of the Chinook. He keyed his microphone to talk to the crew in the front, and suddenly the helicopter’s ramp began to lower. He grabbed my arm again and pulled me to the side.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

I was not prepared for what happened next. Nothing could have prepared anyone for what happened next. As the ramp touched the ground, streams of liquid poured into the grass and dirt. I stared for a few seconds, taking in the dirty reddish-brown color, unsure what I was looking at. The crew chief pulled me even further away from the aircraft, and two firemen in full battle rattle moved in with a small hose and began spraying the ramp in a high-pressure stream.

Get your detail and bring them over, the crew chief seemed to pantomime, and as I trotted over to our pickups, I slowly began to understand the source of the reddish liquid. The troops looked at me with curious faces, but I put on my NCO-knows-best-and-doesn’t-have-to-explain-himself expression.

A U.S. Army CH-47 Chinook helicopter carries a sling load beyond the tactical operations center at Fire Support Base Bandit II near Saigon in Vietnam on Jan. 3, 1970. Photo courtesy of the US Army.

“Form up and follow me,” I said. At the back of the helicopter, we watched one of the exiting firemen take a massive pratfall, both feet in the air. We laughed instinctively.

“Careful,” the crew chief screamed directly into my ear. “It’s slippery in there. Just two guys to a bag, one bag at a time.”

The guys in scrubs inched closer to the helicopter with their gurneys and carts but stopped short of the ramp, and I returned to my waiting crew. Unsure what to say, I grabbed the first two men and indicated for the rest of them to stay where they were. The three of us bent into an unnecessary crouch beneath the helicopter’s whirling blades and started up the slick wet ramp. With no traction, we stepped on the inside of the fuselage. Here it was only marginally better, and we made our way up by comically grabbing hold of each other and whatever else we could to steady ourselves.

The crew chief called us off and brought the fireman back. They spoke for a long time before deciding to mix the water with fire-retardant foam and spray it using a bigger hose. Ten minutes later, foam covered the ramp, and we went back in. At the top of the ramp, we waited several seconds for our eyes to adjust.

Then we saw it. Body bags. Stacked like cords of wood and secured with brightly colored canvas straps connected to hooks on the deck. The crew chief brushed past us and began releasing the straps. The bags settled and spread—six or seven to a pile, multiple piles. We stood with our mouths agape, unable to move until the crew chief slapped me on the shoulder. My two guys grabbed the first bag and lifted it. The body slid into a ball. They lifted higher, until their arms were shoulder-height and the bag cleared the ground. The two troops slithered and stumbled down the ramp. They ought to be in bed asleep, I thought.

The crew chief hit me between the shoulder blades, signaling it was time to take the other end of the next bag. I watched the people in scrubs stand, unmoving, as my two men struggled to lift the first bag onto a gurney. I felt a flash of anger and might have said something had I not looked into their eyes just then and understood. They would open each bag inside the Quonset hut. I could imagine we carried awkward, messy bags. They could not escape the horror of their undertaking.

Two CH-47D Chinooks take off from Soto Cano Air Base, Honduras, for the last time on May 28, 2014. One of the helicopters, affectionately known as “638,” is the oldest active Chinook in the U.S. Army’s inventory, having flown in the Vietnam War. Photo by Capt. Steven Stubbs, courtesy of the U.S. Air National Guard.

Our detail quickly set up an assembly line, ensuring every team member took the same number of turns into the ship, and we each became experts in a macabre parade. I wondered whether the lighter bags held small soldiers or only body parts. I kept no count of the work.

I still don’t know how many we carried. Perhaps 30 or more. Our work took about two hours, and when it was over, no one dismissed us. The freshly cleaned helicopter lifted off. After we’d cleaned our boots in the firemen’s portable canvas pool, we stood alone in soaked socks and jungle boots. No one stayed to tell us what to do, and the men—not much older than boys—looked to me, a 21-year-old with one or two more stripes, to give them guidance, direction, orders. Anything.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

I had nothing.

“Who wants to go back to the barracks and who wants to go to the chow hall?” I offered after a few long seconds of silence.

That evening, as I readied for another 12-hour shift, I looked down at my feet, now the pinkish hue of diluted blood from my boots. No matter how often I washed or soaked those boots, they retained a stiffness, a reminder of a little detail.

Comments are closed.