‘Bridge Man’ Peng Zaizhou’s Mission Impossible and His ‘Toolkit for the Removal of Xi Jinping’

‘Bridge Man’ Peng Zaizhou’s Mission Impossible and His ‘Toolkit for the Removal of Xi Jinping’

China Change, October 19, 2022

‘One man’s anger shakes the earth and moves mountains’

It’s too early to evaluate the full impact of the extraordinary one-man protest staged by Peng Zaizhou (彭载舟), real name Peng Lifa (彭立发), on Sitong Overpass (四通桥) on October 13, 2022 in Beijing. But this much we already know: his action caused a ripple effect across Chinese social media and beyond, eliciting shock, disbelief, admiration, excitement, whispers, and above all, hope, though just how this flick of hope will manifest itself remains to be seen.

Over the years, this website has reported on many activists — brave men and women in China — who put up a fight for freedom and democracy under harsh circumstances and made untold sacrifices for that cause, but few of them are quite like Peng Zaizhou and the feat he pulled off for a few short but enduring minutes on Sitong Overpass. He belongs to a singular category, similar to that of “Tank Man” in 1989.

The source of the shock, and the ensuing emotions, came not only from the daring slogans that resonated with many Chinese, but perhaps more so from the seemingly impossibility of his action in the middle of Beijing’s tight security and the fact that people have been slowly fading into a languor of hopelessness and despair over the past years under Xi Jinping. The Bridge Man jolted tens of thousands of Chinese awake.

So it’s important to understand the perfection with which Peng carried out his action.

The Timing. He chose the day after the CCP concluded the 7th and final plenary session of its 19th Congress, in anticipation of the Party 20th Congress, which opened on October 16. Notably, Xi Jinping is expected to assume an unprecedented third term as General Secretary at the end of the party’s Congress.

The Location. Sitong Overpass is located on the bustling north section of the Third Ring Road. To its south is Friendship Hotel, one of Beijing’s oldest hotels designed to receive foreign guests in Mao’s era, and Beijing Institute of Technology; to its north is Renmin University of China (中国人民大学) and, a short distance down the road is Zhongguancun, where tech companies are concentrated.

The Overpass is 280 meters in length, an enclosed 6-lane expressway bridge that can only be accessed through traffic from either direction. This condition afforded Peng Zaizhou just enough time — a few minutes — to carry out his plan in Beijing’s barrel-tight security before the police and firefighters arrived.

The Action. Peng hung up two large white banners on the side facing Renmin University. He set something on fire that created a beacon of black smoke, while playing a looped recording of his message loud and clear.

The Message. On the banners, and from the loud speakers, Peng broadcast his message:

Say no to Covid testing, yes to livelihood. No to lockdown, yes to freedom.

No to lies, yes to dignity. No to Cultural Revolution, yes to reform.

No to great leader, yes to voting. Don’t be a slave, be a citizen.

–

Students strike, workers strike, remove the dictator and state thief Xi Jinping.

Peng Zaizhou’s message tapped into the widespread anger and frustration towards the Chinese leader that simmers below the artificial calm guaranteed by the CCP’s “stability maintenance” measures. Xi’s move to take a third term as Party chief and Chairman of the People’s Republic of China breaks the unofficial term limit set by Deng Xiaoping and which was adhered to by Xi’s processors to ensure smooth transitions of power. The Chinese people, who have no say in the country’s politics, would have accepted Xi’s move docilely, were his leadership a popular one. But Xi has bred resentment among an increasingly swath of the population, from elites down to the average Chinese citizen. In the years before the pandemic, he was already suffocating society with ever-tighter controls over economic and cultural activities, and restricting the little personal freedom people had been allowed in the heyday of the reform era.

With excessive testing and lockdowns, Xi’s “zero-COVID” policy has disrupted lives of millions, led to untold humanitarian tragedies, and forced businesses around the country — particularly the smallest and most vulnerable — into destitution or bankruptcy, sapping vitality of the economic and social life across the country. So many Chinese have grown so pessimistic and uncertain about a future under the current direction that “run” (written using the character 润, which has the phonetic reading “rùn,” to mimic the English word), has become the latest buzzword.

The Impact. Peng Zaizhou knew he would have only a few minutes of time, and he had only one chance. He made maximum use of the few minute and the one chance. Despite all-out censorship and omnipresent surveillance, people across China have been finding ways to spread Peng’s message on social media, in public restrooms, at bus stations, on city billboards, on the walls of PCR test booths, through AirDrop and WeTransfer, and posting stickers in public using a micro printer…… Outside China, posters with Peng’s slogans appeared on dozens of university campuses in the U.S. and Europe.

A powerful broadside against Xi Jinping, in the form of a long poem, was “making furiously rounds” on WeChat two days ago that proclaims, “that brave man is our spokesperson.”

One tweet by Xiao Han (萧瀚), a former law professor at China University of Political Science and Law in Beijing who was suspended in 2009 for his active participation in public debates about law and constitutional democracy at a time when such discourse was still possible in China, speaks for a lot of people in China right now: “A coward, I admire Mr. Peng Lifa; I am grateful, and also ashamed. In these treacherous times, I pray for Mr. Peng’s safety, and thank you for strengthening my beliefs.”

The ‘Toolkit’

Around 4 am Beijing time on October 13, the day Peng Zaizhou (彭载舟) pulled off the all but impossible protest on Sitong Overpass, a file titled “A Toolkit for Student Strike, Business Strike, and the Removal of Xi Jinping” (《罢工罢课罢免习近平攻略》) was sent to several overseas Chinese language websites, and also posted on www.researchgate.net where he had posted a handful of electromagnetic papers before (they are no longer there).

The file is clearly an integral part of Peng Zaizhou’s action, though we have no way to ascertain whether he himself was the sender — not that it matters that much. The 23-page PDF file has 21 units with a lede that reads, “This is a broadside against the state thief, this is a protest toolkit, this is an election platform, and this is a policy plan, all for the purpose of opposing despotism and save China. Those who violate our human rights must be rejected no matter how powerful they are.”

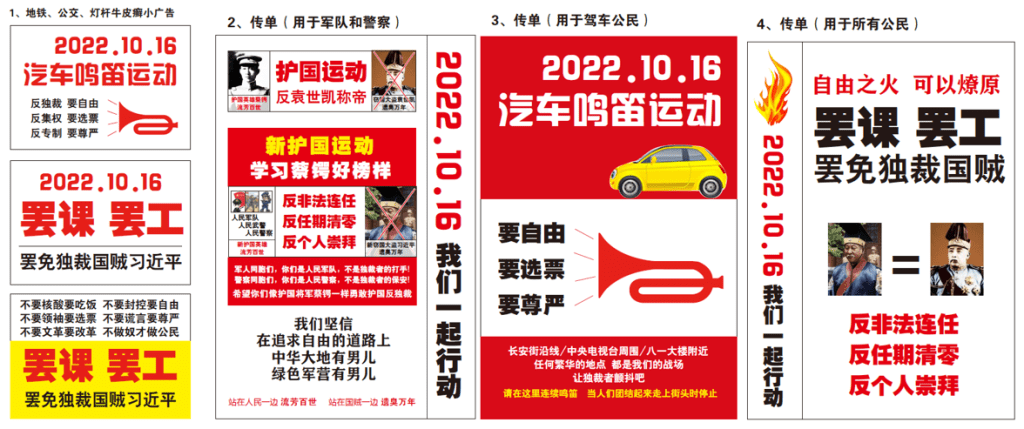

Unit 1, “strategy to fight the state thief” states that the purpose of student and business strikes is to prevent Xi Jinping from illegitimately assuming a third term, and further take China onto a path to freedom, democracy, and prosperity. To avoid a violent civil war, it says, a non-violent, popular participating color revolution is the best way to go. It lays out four principles of protest: decentralize in early stage; form small units in universities and communities; spread truth to as many people as possible, especially to the military, police, and government officials about the dictator, as well as the purpose of our actions; non-violence without hurting innocent people, damaging properties, and committing crimes. The unit concludes with a collection of protest posters for ready use.

He recommends a dozen or so of “methods of protest,” including information warfare, strike, honking at certain locations, disseminating flyers and ads, hanging banners, burning tire, setting up roadblock, sabotaging PCR booth, playing recording during public square dancing, and flying balloons and drones.

Unit 2, titled “a doggerel,” describes some of the dynasty-changing revolutions throughout history, and criticizes Xi Jinping’s rule.

Unit 3 is a letter to the Chinese people signed by the “Universal Suffrage Committee of the People’s Republic of China.” It particularly addresses the “armed forces, armed police, police force, and Chinese people from all walks of life.” Peng compared Xi’s breaking the Party’s rule for power succession to the example of General Yuan Shikai (袁世凯), who made himself an emperor by abolishing the nascent Republic of China in 1915. “One hundred and ten years on, and forty-four years since the Reform and Opening up, the Chinese people are again at the crossroads,” he writes. He calls on the armed forces, the armed police and the police to follow the example of General Cai E (蔡锷) to choose the interest of the nation over personal loyalty and rise up opposing Xi.

Unit 4, “Long Live Ballot,” appears to be lyrics for a song. “A single spark can start a prairie fire. Together let’s light up the fire of freedom, together let’s start the flame of democracy.” …… “The beautiful and civilized China is the home to 1.4 billion people, not the private property of tyrants. My compatriots who do not want to be slaves, stand up bravely. Let’s vote, and let’s campaign for office.”

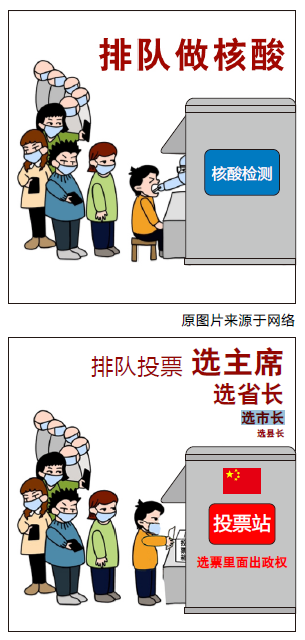

He thinks the PCR testing over the past three years is good training for voting, and all China has to do is to replace the PCR testing booths into voting stations to elect the president, the provincial governors, the mayors, and the county chiefs.

Unit 5, Who We Are. “We are migrant workers from the countryside who have no social security. We are people on the bottom rung of the society who cannot afford medical treatment. We are jobless, drifting from one temp to another. We are college graduates with a degree but no job. We are employees of the extracurricular education sector whose livelihood was taken away by government order. We are the low-end population who have been cleared out of big cities. We are law-abiding small and micro business owners whose shops are shut down. We are service providers on the brink of bankruptcy. We are people who are either defaulting on our mortgage, or contemplating jumping to our deaths; we are either enslaved by a mortgage that depletes the savings of three generations, or families that dare not to have children. We are migrant workers in cities from the countryside, leaving our children behind. We are parents in provinces where the threshold for college admission is the highest. We are high schoolers who must separate from our parents and go back to our origin to take the college entrance exams. We are the chained women, trafficked and sold with no hope to ever gain freedom. We are defamed intellectuals and educators. We are native residents whose homes are expropriated by force. We are second-class citizens who buy cars or enroll children in school by lottery.”

“In short,” he writes, “we are neither the people nor the masses featured in the dictators’ slogans.” “We must stand up bravely. We want to establish our own organizations and our political parties to fight for our interests and our rights.”

The statement is signed off as the “Universal Suffrage Committee of the People’s Republic of China” and the “Chinese Communist Party Free Elections Committee.” Peng calls on citizens to join the former; the person who receives 50% support of the committee will represent the body to compete for the office of the State Chairperson (国家主席). Similarly he calls on the CCP members to directly elect its party’s General Secretary.

Unit 6 calls for candidates for these two bodies and lays out how candidates will be selected. Unit 7 cites the Constitution of PRC, as well as the Communist Party’s constitution as “the legal bases for us to compete for office.”

Unit 8, titled “A Brief Explainer: What Is Government and What Is State,” explains that, as taxpayers, citizens are the boss, not the servant, of the government and the state. As an example, he writes, “I’m a citizen from Heilongjiang province (黑龙江省), I love my home and my neighbors but I do not love the party secretary and governor of Heilongjiang, I do not love a certain mayor or county chief, because I’m a taxpayer and we taxpayers pay them to work for us. …When I criticize them for their incompetence, I’m neither a traitor nor a hater of the party.” We must have the right to elect government officials and the right to impeach them, he continues, and we can no longer pay the bill for their ineptitude.

This reference to his home province confirms information circulating online that Peng Zaizhou is from Heilongjiang. Assuming the rest of his personal information online is correct, he was born in 1974, 48 years old, likely a graduate of Heilongjiang University.

Unit 9, “Our Action Plan,” proposes that the CCP’s 20th Congress elect an interim General Secretary and draft a plan for members directly elect the party leader; an independent review body be established to investigate Xi’s abuses and the corruption of his family, how the trillion-yuan investment in Xiong’an New District (雄安新区) was decided and whether it was approved by the National People’s Congress, the One Belt One Road investments, and corruption in COVID-related spending; a power transition committee be established to recommend interim President for a one-year term, while amending the Constitution, approved by a referendum, to set rules for direct election of the president; and a national solidarity and reconciliation committee be established to unite the people for a free and democratic system of government.

In Unit 9, “Our Campaign Promises,” he offers templates for campaign platforms in politics, pandemic-prevention, education, people’s livelihood, law, economy, technology and innovation, foreign policies, defense, Taiwan-Hong Kong-Macau, and sports and culture. Notably on the unification with Taiwan, he rejects military solutions and proposes the matter be determined purely by referendum. He supports the right of the Hong Kong and Macau people to elect their chief executives through universal suffrage.

In Units 10 through 17, he lays out details on governance through meritocracy, pandemic policies, streamlining government, constitutional democratic reforms, anti-corruption and government oversight, financial and taxation policies, and economic reforms.

Peng proposes that constitutional democratic reforms be based on Charter 08, and a full text of the document is included.

His proposed streamlining of the government, by his estimate, will save more than six trillion yuan a year.

Units 18 to 20 are three appended articles. They are: Citizen Movement leader Xu Zhiyong’s “Dear Chairman Xi, It’s Time for You to Go” (《劝退书》); an argument against lifelong leadership terms (终身制) by Lao Gui (老鬼), a writer and dissident in Beijing; a Chinese translation of “How to Start a Revolution – 4 ways” (author unclear) posted on a Chinese-language website.

Peng Zaizhou’s Toolkit ends with a copyright statement (Unit 21). He says he’s the original author of most of the content in the kit and he welcomes dissemination. He apologizes for possible copyright violation for the articles reproduced in the kit, and leaves china.puxuan@gmail.com as his contact.

Peng Zaizhou’s Fate

Over the past twenty years or so before Peng Zaizhou, three Chinese at different times have ventured an actual blueprint for a democratic China, even though the subject has been a matter of constant discussion among dissidents. The first was Peng Ming (彭明), a successful executive of two state enterprises in Beijing in late 1990s. His “The Democracy Project” is a practical handbook, providing specific advice for the set of institutions that would replace the CCP, as well as the means of a prospective opposition movement to do so.

The second is Liu Xiaobo (刘晓波) who led the drafting and publication of Charter 08, a manifesto initially signed by 303 Chinese, in 2008. Liu Xiaobo was the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010.

The third is Xu Zhiyong (许志永), a legal scholar and a leader of New Citizens Movement, who, in a series of essays published on his blog around 2012-2013, laid out a plan for the structure and the institutions of a future democratic China. Under the subtitle “To Chinese Citizens” (《致中国公民书》), this set of essays is collected in the Chinese edition of “To Build a Free China – A Citizen’s Journey” but, regrettably, not in the English translation.

Peng Ming, serving a life sentence, died in prison in November, 2016, aged 58. Liu Xiaobo, serving an eleven-year sentence, died in prison in July, 2017, aged 61. Xu Zhiyong was imprisoned for four years from 2013 to 2017, arrested again in early 2020, and tried this June with verdict still pending. He is 49.

Peng Zaizhou is the fourth man to articulate such a blueprint and call upon the Chinese people to work on bringing their country to a constitutional democracy. He draws inspiration from Liu Xiaobo and Xu Zhiyong.

No one should be locked up, let alone die behind bars, for having such aspirations for their country’s future.

Related:

Identity of the Man Who Pulled Off Protest on Beijing Overpass Amid Unprecedented Security Before the CCP Congress, China Change, October 13, 2022.

Comments are closed.