Nobody Leaves War Emotionally Healthy. The Path to Recovery Is Unique to Each Person.

The U.S. military always takes care of its own when Thanksgiving rolls around, no matter what part of the world you’re in. In November 1968, that place was the fishing village of Rach Gia, where I spent the final five months of my year-long tour in Vietnam helping direct air strikes against the Viet Cong as an Air Force buck sergeant.

Nestled on the southwest coast of the Mekong Delta, Rach Gia was a long way from any major military installation, but the Army found a way to feed us a Thanksgiving meal—turkey, stuffing, mashed potatoes and gravy, cranberry sauce, and pumpkin pie delivered by helicopter in large, insulated containers. Just like mom made. Well, sort of.

Ted Englemann spent Thanksgiving 1968 in a remote fishing village in Vietnam, where he helped direct air strikes against the Viet Cong as an Air Force buck sergeant. Photo courtesy of the author.

Four decades later, I found myself celebrating another Thanksgiving on the other side of the world, this time as a freelance photographer assigned to an Army combat outpost in southwestern Baghdad, where I observed one of America’s new “forever wars.” A lot had changed—I had changed—but the turkey and fixings arrived in the insulated containers I remembered from Vietnam.

My road back to a war zone had begun not long after my discharge from the Air Force in 1970. I struggled to adjust to civilian life—I was always a few years older than my college classmates and, unlike most of them, I tried to make sense of a year spent at war. I grabbed piecemeal jobs to pay rent and put gas in my car, and life felt disjointed, lonely, and stressful.

By the end of the decade, the Colorado Disabled American Veterans hired me as its first veterans service advocate for the Vietnam Veteran Outreach Program. I took inventory of veterans’ needs, providing them with gas vouchers and bus tokens, and connecting them with other organizations for food, shelter, and other support systems within the community. I also scheduled group counseling sessions provided by two graduate students at the University of Denver—both former Marines and combat veterans.

In 1980, the American Psychiatric Association added post-traumatic stress disorder to its list of mental disorders. Although initially controversial, the Department of Veterans Affairs finally had the push it needed to start treating our emotional wounds at hospitals and newly created veterans centers throughout the country. Our DAV program eventually closed, and in the intervening years, I taught middle school science and photographed veteran parades and memorials around the U.S., Korea, Australia, and Vietnam, where I would spend the next three decades photographing the recovering country.

Through it all, my interest in the impact of war and those who fought in it persisted. I knew a few local Vietnam veterans who’d died by suicide, and I’d experienced my own “discouragement” from time to time—my code word for depression. And I knew that decades after my own service, veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars were dying by suicide at rates that outpaced civilians. I needed to understand why. I needed to know if the war in Iraq was anything like Vietnam.

A lighter from Vietnam. Four decades after serving in the Vietnam War, Ted Englemann spent time with soldiers in Iraq as a freelance photographer. Photo courtesy of the author.

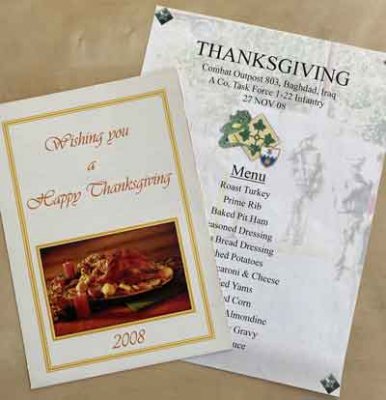

In 2008, on the heels of the troop surge in Iraq, I embedded with the Army as a freelance photographer, documenting the lives of soldiers at war—how they lived, where they ate and slept, and their operations between Baghdad International Airport and Sadr City. Their Thanksgiving meal.

In keeping with tradition, the Army delivered hot food containers to the units that couldn’t make it to the large dining facility, or DFAC, and officers went to work preparing a traditional Thanksgiving feast. Within an hour, hungry enlisted soldiers lined up with plastic utensils and styrofoam plates that officers heaped with generous helpings of delicious-smelling food. They found seats around a few picnic tables protected by sandbags inside a compound reinforced with blast-resistant cement “T-walls” that stood more than a foot thick and rose some 20 feet high.

Before I got my own plate, I roamed around the compound for a while taking candid photographs of the soldiers enjoying the best meal they’d had in a while. I paused at one table where eight soldiers chowed down on turkey slathered in gravy and asked them to look up so I could capture the moment. Click.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

Later, that photo would haunt me. But for now, it was just one image out of the thousands I took in my weeks there, and I said thank you before moving on. Two weeks later, my embed came to an uneventful end. I headed back to snowy Denver and hunkered down for the winter.

Ted Englemann spent Thanksgiving 2008 with soldiers in Iraq. Photo courtesy of the author.

An email arrived in mid-February from a soldier named Chris I’d met in Iraq. Chris wrote that he’d had lunch with a fellow soldier on Valentine’s Day. The soldier was excited to return home in a couple of weeks and told Chris about plans to take a fishing trip with his family. After lunch, the soldier dumped his tray and plasticware like always. Then, inexplicably, he’d gone to his living area, picked up his gun, walked around the back of the building, and entered the back of an armored vehicle. Chris told me he died of a single gunshot wound. The soldier had been one of the eight whose image I captured enjoying their Thanksgiving meal.

Thanksgiving menus from Combat Outpost 803, Baghdad, Iraq. Photo courtesy of the author.

Chris had no idea why he’d done it, and the news shocked me, too. A couple of months later, he told me that the Army had medically discharged two of the other soldiers from that picnic table. The reason, he told me: post-traumatic stress. Three out of eight seems like a very high casualty rate. I imagine the other five who walked away from that table carry their own emotional wounds, too. The path of recovery from trauma is unique for each person. Nobody leaves war emotionally healthy.

While in Iraq, I’d connected with many of the soldiers I photographed and shared my story of returning to a country where I’d once fought. I’d told them about the warm welcome I’d received from the Vietnamese, and about my photographic memoir describing my time there.

Soon after Chris rotated back to the U.S., I received another email from him—this one inspiring and full of hope.

Ted,

Thanks for letting us be a part of what you’re doing. There are a lot of us here that were pretty inspired by it. You definitely showed us that after all this is over and the smoke clears, life goes on. Personally, I know I am forever changed by what I have experienced here, for better and worse. It’s good to see time does heal the wounds of war that we all carry with us. I sometimes wonder if the innocent people here will ever forgive us for all the pain and damage that we are sometimes forced to cause. …

The experiences you shared about your return to Vietnam showed us that we may be yet forgiven for the evil that those who are fighting us cause us to do. I look forward to reading your book, and I have told my father about it. He is eager to find out what the country that “stole his youth” has developed into.

I would love to have copies of the photos you took to remind me of this place. Maybe I can look back on them years down the road and have a better understanding of the history we are all part of. Once again, thank you, Ted. Hopefully we will talk one day without the threat of war around us. Take care.

A Soldier

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

Traveling to Iraq left me with a continued understanding of wartime trauma but not why some people’s paths end in suicide. Maybe it has to do with our fragmented and isolated society, especially for those who served in combat, or fighting a contrived war.

But as I read Chris’ words, I realized that maybe I was living proof for some of the soldiers that pain does not have to last forever. I know it is up to all of us to offer a hand to those struggling with emotional wounds. We’ve all been there in one way or another. In many ways, we still are.

Comments are closed.