A Good Country, A Good People – Thirty Days Around Taiwan

A Good Country, A Good People – Thirty Days Around Taiwan

Yaxue Cao, December 31, 2022

In the coming weeks and months, China Change will start publishing a series of interviews conducted in Taiwan during a recent trip. The following article may be taken as an introduction to the series. Stay tuned. — The Editors

A Trip to Taiwan

In early November, I embarked on a four-week trip to Taiwan, propelled by bouts of anxiety about the specter of military aggression from the People’s Republic of China. At times I had the ominous thought that the Nine-In-One elections (九合一選舉) to be held on November 26, might be the last free elections in Taiwan (nominally governed as the Republic of China) the world would see.

It was my fourth trip to Taiwan, but unlike the three before it, I felt an obligation to stay longer and talk to people in depth as I had not done before.

Before, during, and after U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in early August, China conducted the largest military exercises all around Taiwan, involving navy ships passing through the sea off the coasts of Taiwan, scores of fighter jets flying into Taiwan’s Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ), and missiles launched around and across the island. According to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the exercises covered coordinated blockade, sea assaults, land strikes, and air battles. China has continued ever increasingly military menacing since.

Since last November, and more recently, mainstream media began to sketch out scenarios of how military strategists believe a Chinese invasion might play out.

In October, Xi Jinping secured his third term (breaking the Party’s unofficial term limits), further consolidating his position as China’s supreme leader, and filled the Politburo with loyalists. By all appearances, he was ready to expedite “the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation,” in which taking over Taiwan plays a central role as indicated repeatedly in his speeches as Party boss. During the Party Congress, Xi promoted General He Weidong to the position of the second vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission. Formerly the commander of the Eastern Theatre Command responsible for Taiwan operations, He oversaw the military show of forces surrounding Taiwan in August. As noted by military analysts both inside and outside governments, the composition of the CCP’s new Central Military Commission signals Xi’s seriousness about using force against Taiwan.

In an unusual comment in October, Secretary Antony Blinken said China had made a “fundamental decision that the status quo was no longer acceptable, and that Beijing was determined to pursue reunification on a much faster timeline.”

Something else also aggravated my anxiety: the American public is poorly prepared for a possible military confrontation between the U.S. and China. In a hypothetical lawn chat about the Taiwan conflict with my neighbor, I am afraid that Mrs. Gray would exclaim, “Where the heck is Taiwan?” I dare not to have that lawn chat with my neighbors. So I had to go to Taiwan not just for myself, but also for Americans.

Life in a Prospering Democracy

I landed in Taoyuan Airport in an early morning, and started the day with a breakfast of hot, fresh soy milk, deep-fried dough sticks (油條) and sesame flat bread (芝麻燒餅) at a small, bustling eatery. It felt right.

After breakfast, our small team of three, two Taiwanese friends and I, headed out in a car to Hualien (花蓮) on the east coast of the island. In Taipei and along our way, on street billboards, on the sides of buses, on fluttering flags, and on country roads passing through rice paddies, we saw colorful campaign advertisements for candidates for mayors (市長), legislative councils (市、縣議會), county executives (縣長), township executives (鄉長), and neighborhood heads (里長).

In Hualien, we interviewed a candidate for Hualien County Council; the head of an environmental advocacy group; a recluse painter who, with a camera on shoulder, recorded the street protests that swept Taiwan in late 1980s and early 1990s; an indigenous professor who studies ethnic relations and indigenous culture; a “mainland spouse” who has become a Taiwan citizen; a European policymaker at the European Parliament for many years and now teaching at the National Dong Hwa University.

On the road and between stops, we attended campaign rallies of several council member candidates and township executives, visited campaign offices, and watched candidates’ street canvassing. We filmed the blue sea, the rice paddies of the Huadong Valley, the quietly flowing Siaokuluan River (秀姑巒溪), and the Central Mountains (中央山脈) shrouded in mist.

100vw, 1000px” data-recalc-dims=”1″></a><figcaption class=) DCIM\PANORAMA\100_0020\DJI

DCIM\PANORAMA\100_0020\DJIThe five days in Hualien seemed to have set a tone for the rest of our trip. In the following weeks, we visited government offices, campaign headquarters, and civil society organizations; we attended more campaign rallies, and toured museums of Taiwan history and its transition to democracy. We swung into temples and churches. We talked to two dozens more Taiwanese, including the executive of a new civil emergency response training group; student leaders of the Wild Lily Movement in 1990 and the Sunflower Movement in 2014; a Taiwanese businessman who has returned from China; a newly elected New Taipei City Council member who had served in Taiwanese Army’s Special Forces; a campaign manager of a mayoral candidate; a Taiwanese who served five years in prison in China for “subverting state power,” a political science professor and a literature professor; a Hong Kong performance artist who now lives in Taiwan; a historian of Taiwanese struggle for democracy; a community activist promoting civil political participation; an incubator of community renewal and start-ups; retired military officers; the chairwoman of the National Taiwan University Student Association; a bookstore owner; an editor of international news; taxi drivers; and others.

Walking around Taiwan’s cities and in the countryside, you don’t feel the menace of war. I tried to discern signs of a society in crisis and anxiety, but everywhere I went, I saw politeness and peace. To be honest, I don’t know exactly what I expected to see. War and peace are only separated by a line. What was I supposed to see on my journey except Taiwanese going about their everyday business?

Preparing for War vs. Avoiding War

But hints of war — at least the threat of it — did show themselves. At the Hualien train station, roaring fighter jets, two in a group, flew overhead. In Taitung and Tainan, I also saw or heard of fighter jets several times. The locals told me it was the norm now. Under the street number plate of many residential buildings in Taipei, you’d see signs of air-raid shelters with capacity numbers on them. In more than one civil society organizations as well as government offices, people were engaged in fact-checking fake information. Whether from China or locally generated, this form of propaganda aims to sow confusion, doubt, division, and hate in Taiwan.

Less than a year ago, a researcher in international relations, a professor and social activist, and a young politician from the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), founded two separate civil emergency response training programs, Kuma Academy (黑熊學院)and the Forward Alliance (壯闊台灣), to train citizens in modern warfare understanding, emergency sheltering and response in order to shore up the society’s ability and resilience to face a possible conflict. A crowdfunding campaign by one of the programs was a success, and a billionaire followed up by committing billions of Taiwan dollars in the next few years. Tickets for classes were snatched away fast.

In a cafe outside the New Taipei Sports Complex, Lin Pingyu (林秉宥), the newly elected member of the New Taipei City Council, told me that he was in the Special Forces when he served in the army and he’s still taking part in special forces training now. He’s also been a researcher, with an advanced degree, on Taiwan-China relations and China’s United Front Work activities in Taiwan.

A taxi driver said, he is fifty years old — well beyond conscription age — but if the country needs him, he will serve. “Taiwan is my home; I’ve got nowhere else to go,” he said.

The two major political parties, the DPP and the Nationalist Party (KMT), have displayed very different approaches to the China threat. At an intersection in Tainan, a group of DPP supporters held a banner that read, “Voting for pro-China candidates is to encourage Xi Jinping to attack Taiwan.” A KMT legislator, meanwhile, asserted that: “Vote DPP, young people go to war.”

Former President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九, 2008-2016) posted an article on Facebook two days before the elections, saying that the Tsai Ing-wen administration should learn the tragic lesson from the Ukraine-Russia war, and proactively seek peace and avoid war. When answering a question about how the KMT would respond to the war risk, the campaign manager for KMT candidate for Taipei mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安), a great-grandson of Chiang Kai-shek who is now elected and sworn in, called to “avoid war through dialogue with China.”

I can’t imagine what kind of “peace-seeking” dialogue it would be. No one wants war, but what conditions Taiwan will have to meet, under what circumstances, to make the Chinese Communist Party give up its military aggression and desire to overtake Taiwan?

No one believes in the One Country Two System anymore after Hong Kong. In one after another survey, over 80% of Taiwanese are against “reunification” with China, over half are in favor of Taiwan becoming an independent country. “Taiwan is already an independent country,” I heard Taiwanese saying over and over again, “with all the elements of an independent, sovereign country.”

To my regret, I had few opportunities to speak with more people from the KMT camp. A young rising star in the KMT agreed to my request for an interview, but my questions had to be subjected to prior Party approval. The interview was declined.

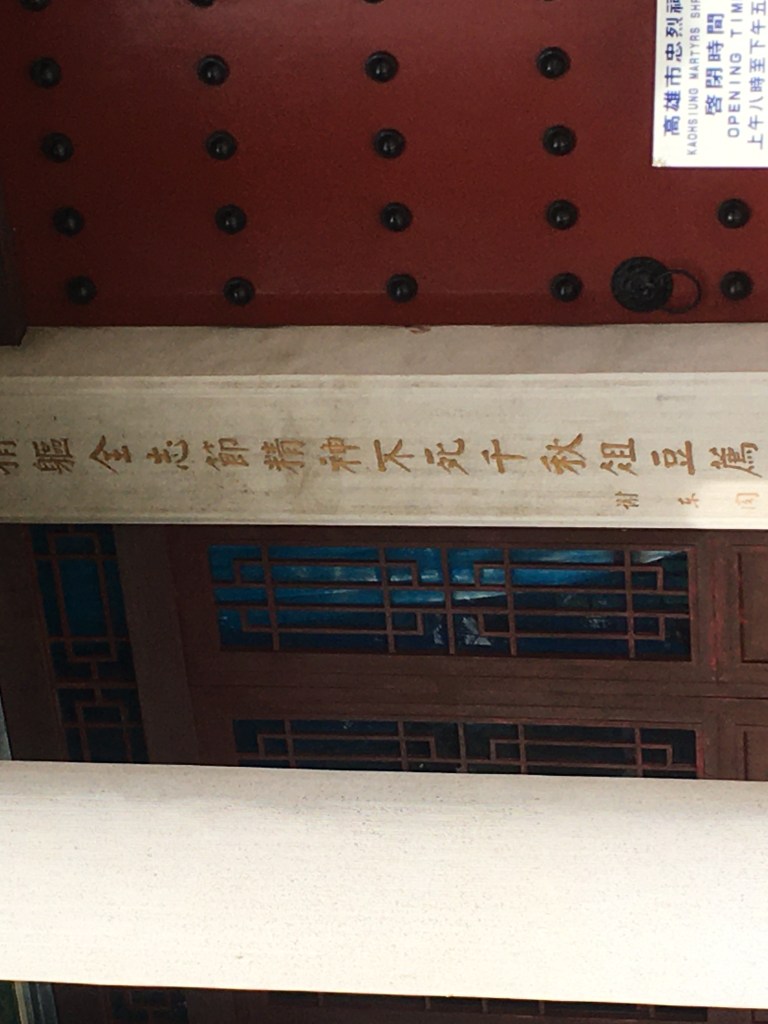

When we met with a retired Navy colonel in Kaohsiung per appointment, he received us warmly and drove us to Shou Shan (壽山) where we toured the National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine (忠烈祠), and enjoyed the spectacular view of Kaohsiung Harbor. Afterwards he treated us with “the best sundae in Kaohsiung.” However, it was clear from the beginning that he did not intend to give me a proper interview and evaded answering most of my questions. He was dismissive of the content on the China Change website. But in the course of our derailed conversation, he made one of the strongest statements I heard on this trip: “I’d rather be ruled by the most tyrannical monarch, the First Emperor of Qin (秦始皇), than let Taiwan be an independent country.”

The DPP suffered losses in the elections. Some say it’s because the population rejected the DPP’s call to “Resist China, Defend Taiwan” (抗中保台). Knowing little about regional politics in Taiwan, I am in no position to comment. Whether “Resist China, Defend Taiwan” is the most appealing call during local elections is open to debate, but if the Taiwanese think they would be exposed to greater risk of war if they vote for one party and safe if they vote for another party, they don’t understand the CCP and Xi Jinping. The CCP China wants Taiwan’s technology and a position to project power into the Pacific; Xi wants Taiwan for his political legacy, the crown jewel in his “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation.”

President Ma seems to regard the Russian aggression against Ukraine as the result of mistakes made by Ukraine that Taiwan must avoid. But almost no one I spoke with thinks this way. On the contrary, they watched the war in Eastern Europe closely and found inspiration and strength from the Ukrainians’ bravery and determination in defending their country.

Ho Cheng-hui (何澄輝), CEO of Kuma Academy, said to me, “If you want peace, you must prepare for war, not avoid it. You can’t give up your dignity and capitulate thinking you can retain the free and democratic way of life that Taiwan has achieved step by step through many years and for which we’ve paid a high price. Faced with this situation, the only thing you can do is to be strong, to prepare for it.”

He said, it’s a very important matter whether the society could withstand war. “It’s probably the most important part of it.”

I agree. I think the Taiwanese society as a whole needs to prepare for war and build up the will to resist. This is the strongest deterrent against aggression, also the best way to mobilize international support.

The Authoritarian Era and the Taiwan Identity

As someone who came of age at the onset of China’s opening up and reform, the years and dates on the trajectory of Taiwan’s transition to democracy are strikingly familiar: 1979, 1987, 1989, 1990…because they were also significant dates for my generation of Chinese, easily the most memorable landmarks of our life. But separated by the Taiwan Strait, China and Taiwan have walked two parallel lines, one remaining a tyrannical one-party dictatorship and a persistent threat to not only Taiwan but also the liberal world order, another a vibrant democracy with political pluralism and an open society.

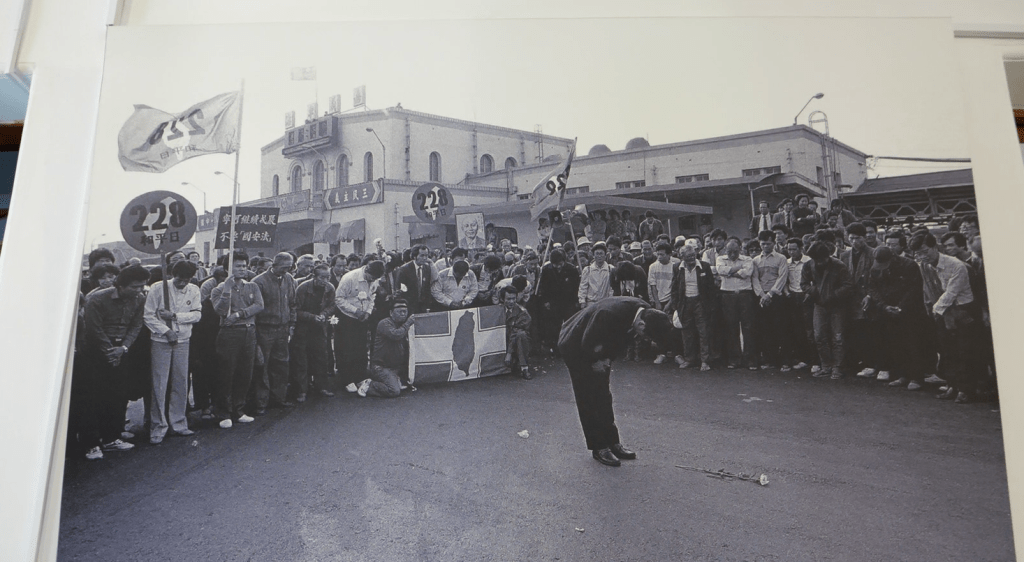

In the National 228 Memorial Museum, Dr. Chen Chia-hao (陳家豪) gave us a brief recap of the first bloody crackdown on local Taiwanese by the Chiang Kai-shek regime starting February 28, 1947, known as the White Terror, and the Taiwanese’ resistance, including armed resistance. Many ordinary and elite Taiwanese were killed or executed. This historical event had been for decades a taboo subject during Chiang’s rule in Taiwan, and public discussions were suppressed. It wasn’t until the 1980s when studies and calls for redress began to surface in Taiwan. The museum was approved in 2006 by the Executive Yuan, and opened on the 65th anniversary of the event.

Photos of the dead, news clips of the time, and a memorial wall aside, it so happened that the museum was exhibiting the works of native Taiwanese painter Lee Shih-chiao (李石樵1908–1995). Valued over hundreds of millions in Taiwan currency, two of the largest paintings, The Market (市場口) in 1946 and Construction (建設) in 1947, are vivid representations of class. Dressed in modern attire and wearing sunglasses, the newcomers from mainland China were the high class and supervisors, while local Taiwanese were the peasants in the market and coolies on the construction site chiseling or moving slabs of rocks.

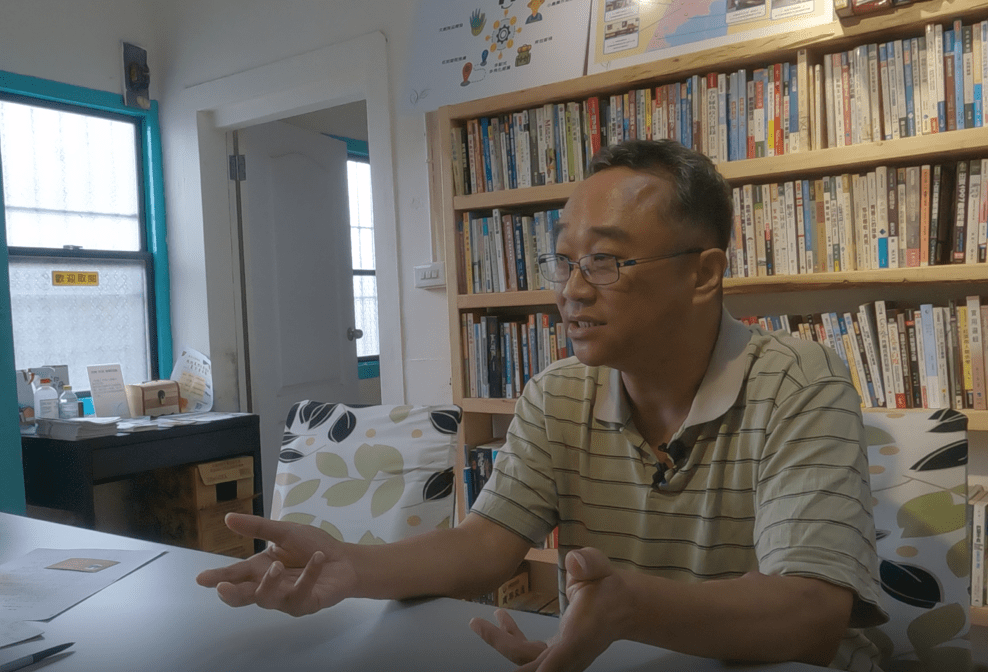

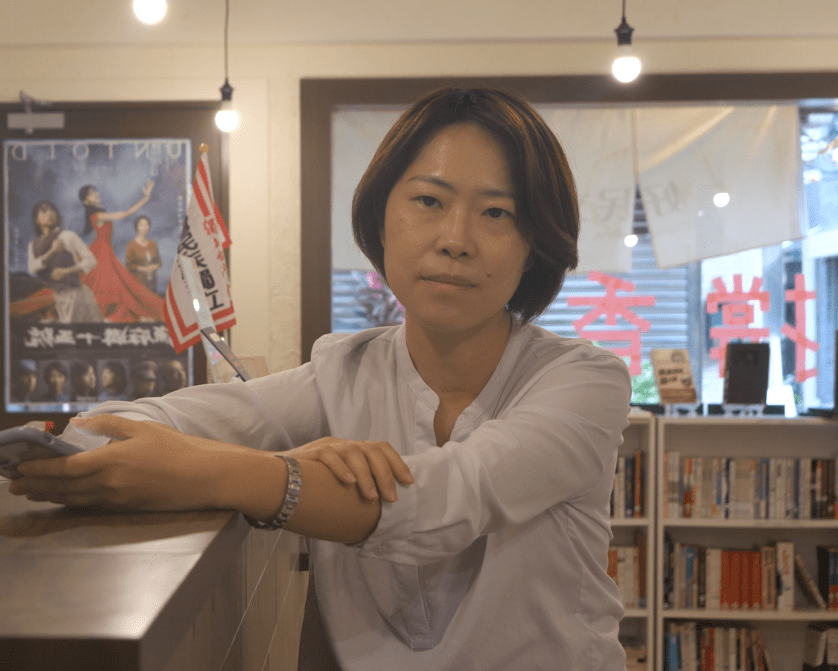

The bias against the locals, reinforced by decades-long state-controlled propaganda, is still the mindset of many older people, and exists in the generational gap of many families. In Thok Phai bookstore (讀派書店) in Taipei, I interviewed Lee Ming-che (李明哲). He was released this spring from a prison in Hunan province where he served a five-year sentence for “subverting state power” after being arrested in 2017 when entering China, a result of him promoting democratic ideas on Chinese social media and helping families of political prisoners there. Born in 1975, he grew up in a typical family of mainlanders who had retreated to Taiwan at the end of the civil war with the communists. In high school in late 1980s and early 1990s, reading Taiwan history and the work of the Tang-Wai Movement (黨外運動, that is, the political opposition outside the ruling KMT) by people whom his mother had regarded as “very bad people,” he began to wake up to his sense of identity as a Taiwanese.

In May, Lee said before the Legislative Yuan that “I’m a second-generation of mainlanders, but a first-generation of Taiwanese. I’m a native Taiwanese, I have rights as well as obligations with regard to Taiwan. I love Taiwan and belong to Taiwan.”

However, talking about the elections, an old Taiwanese friend from a native Taiwanese family defended his favorite view of the KMT: “Old people used to say, the KMT are people wearing leather shoes, the DPP are people wearing straw sandals.” Stunned and speechless, I said, it’s very nice to see you, I’m not going to argue with you.

Jing-Mei White Terror Memorial Park (白色恐怖景美紀念園區) is the site of a prison for political prisoners and a military tribunal in the authoritarian era where, in early 1980, dissidents involved in the Formosa Incident (美麗島事件) were tried for “insurrection” (“叛亂”) for their pro-democracy protest in Kaohsiung on the International Human Rights Day in 1979. They and their defense lawyers would become the founding members of the Democratic Progressive Party in 1986, the first opposition party in Taiwan.

There were group visitors there, and I joined seven or eight loose ones. Several were high school students who held notepads completing school assignments. A young lady said she was interested in becoming a guide and would like to see what it was like. I was the only person with gray hair. I said I came from the United States, was born and raised in China, I oppose the CCPs totalitarian rule, and I was here to take a look at the prison and the tribunal from the authoritarian era under the KMT.

The guide took us to see the prison cells one by one. He showed us the thick iron shackles worn by prisoners. A young man tried to fit a foot in them. I interjected, “Do you know that there are still political prisoners in China? Those who oppose Communist rule are still being thrown into prisons as we speak, and they are still wearing similar shackles and suffer torture even more barbarian than during Taiwan’s authoritarian era.”

Vividly, the guide described how prisoners were taken out to be executed before daybreak, and the sound of the shackles made on the cobblestones in the dead quiet of the early hours.

Among the prisoners were mainlanders, Taiwanese, overseas Chinese, and aboriginals. Some of those arrested and tried were those who had accompanied Chiang’s Nationalist government during the retreat to Taiwan, but wrote letters to family in the mainland; in doing so, they had committed “the crime of colluding with the enemy.” Meanwhile, those who promoted Taiwanese identity and an independent Taiwan committed “insurrection,” the worst crime of all.

“We’ve preserved the site, the scenes,” the guide concluded our tour, “so that people different backgrounds can come here and learn that part of the history, and together to live the hard-earned lifestyle of freedom, democracy, human rights, and the rule of law, and never go back to that authoritarian era of white terror.”

On Green Island (綠島), locally known as Fire Burning Island, off the coast of Taitung, we toured the National Human Rights Museum (國家人權博物館), another prison complex for political prisoners from early 1950s to 1980s. Part of its jail cells looked almost exactly like those in the Nazi concentration camps. On the wall of victims, I found names that I recognized. Some I knew before, Shih Ming-teh (施明德), Lü Hsiu-lien (呂秀蓮), Chen Chu (陳菊)…; others I only learned on this trip, Kao Chun-ming (高俊明), Huang Kuang-hai (黃廣海)… It wasn’t until May 1990 that the last prisoner, Wang Sing-nan (王幸男), was finally released.

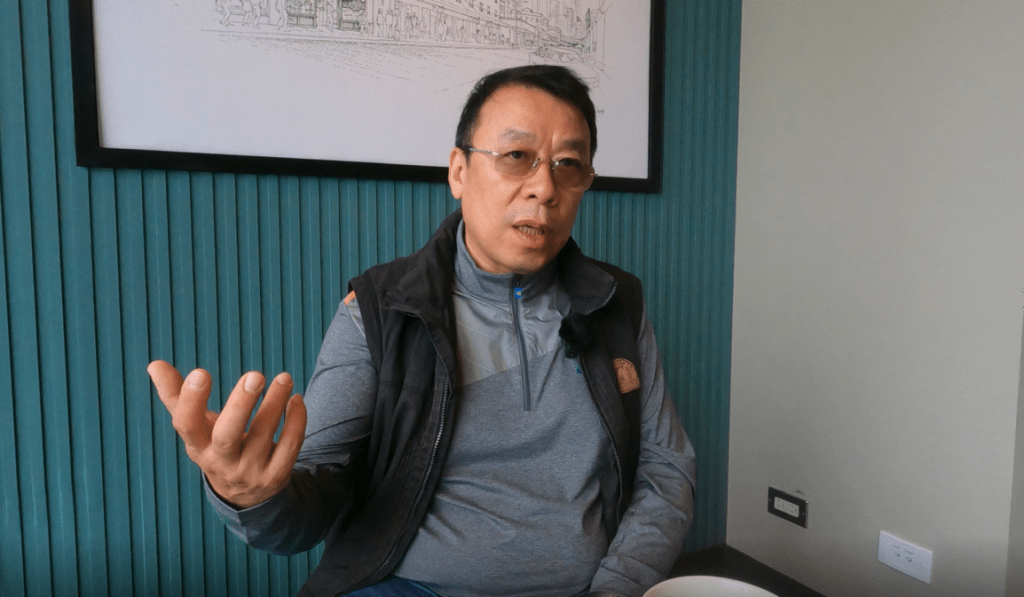

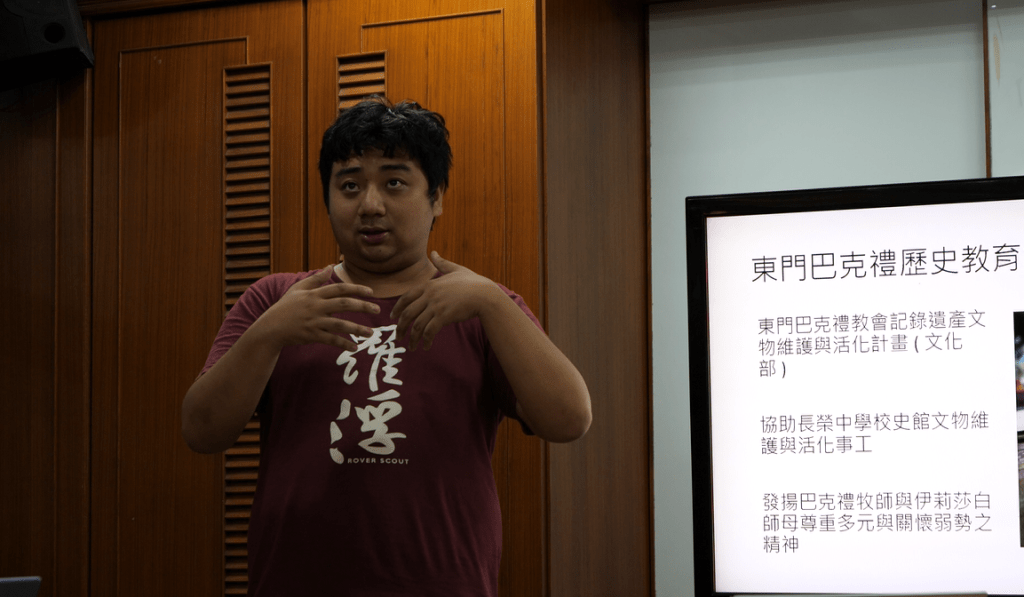

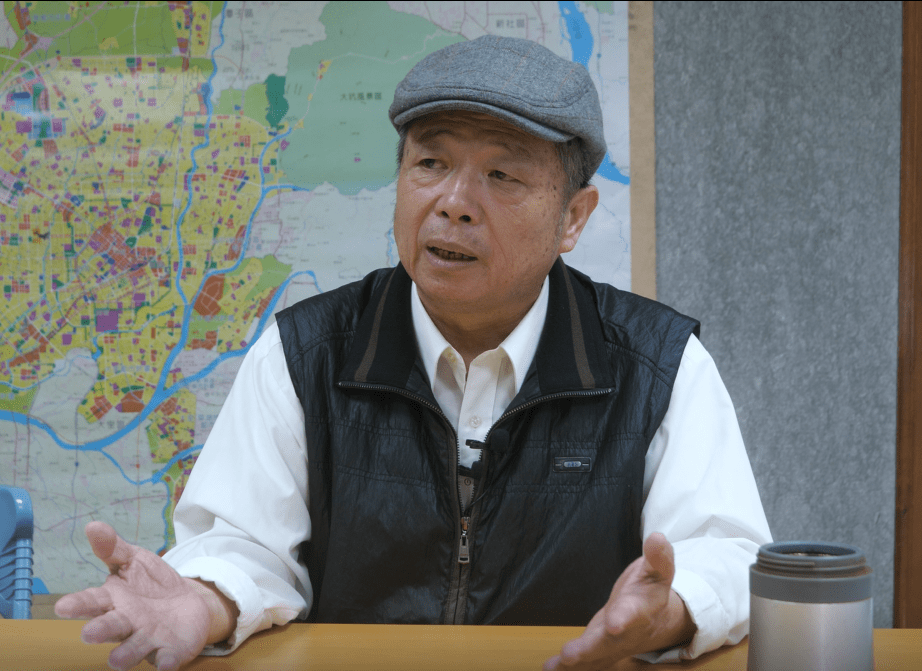

In a countryside courtyard in Wanluan Township, Pingtung county (屏東縣萬巒鄉), we interviewed Chou Ke-Jen (周克任), Taiwan’s own “1989 generation.” A college sophomore in Taipei, he was one of the initiators of the Wild Lily Student Movement in 1990 (野百合運動). The demands of the students were “abolish the National Congress,” “abolish the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of Rebellion” (動員戡亂時期臨時條款), two relics of the authoritarian era, “hold a national affairs conference” (國是大會), and formulate a timetable for political and economic reforms. In Beijing in 1989, the student protests ended with a massacre; in Taiwan, then-KMT President Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) responded to student demands positively, taking another significant step to advance Taiwan’s transition to democracy following Chiang Ching-kuo’s (蔣經國) removal of martial law in 1987.

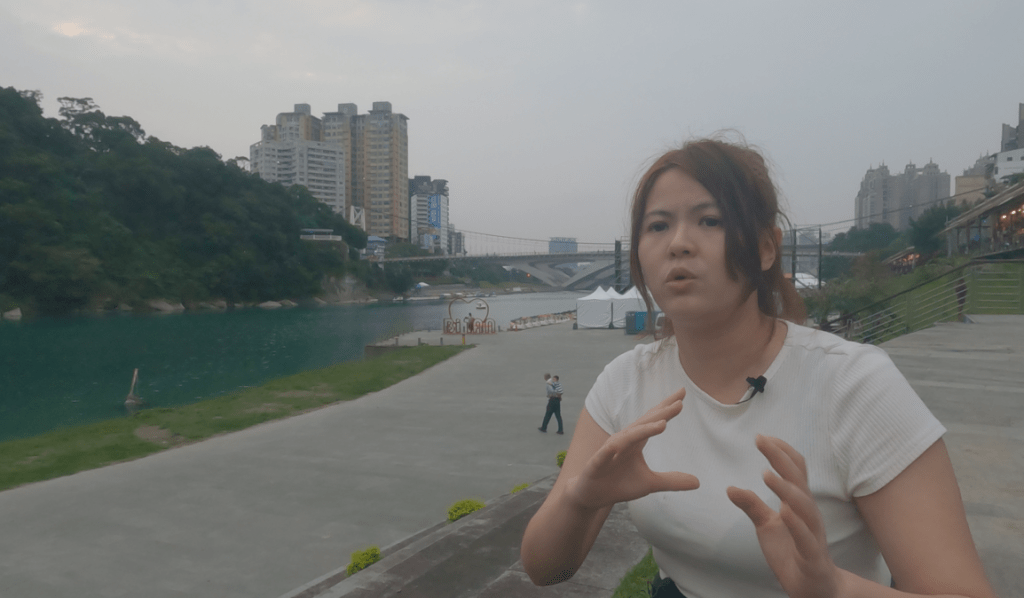

On the bank of the Tamsui River (淡水河), northwest of Taipei, 34-year-old Wu Jun Yen (吳濬彥) started his interview with these words: “I want to begin by positioning my generation’s political ideas and historical perspective.” “I was born in 1988,” he continued, “it wasn’t until two years before I entered middle school when schools in Taiwan implemented classes on Taiwanese society, history, and geography. Prior to that, we were taught to memorize Chinese geography, where each province is, and what are all the ethnic groups in China, etc. Little was taught about Taiwan itself.”

During the Sunflower Movement in 2014, Wu was the first to scale the wall and entered the Legislative Yuan. Students and civic groups occupied the legislative body for 23 days and eventually stopped the ratification of the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (《海峽兩岸服務貿易協議》) that had not had prior consultation with the public and would move Taiwanese economy far too close to China and strengthen Beijing’s political influence over Taiwan. Wu and his friends are Taiwan’s new generation of defenders.

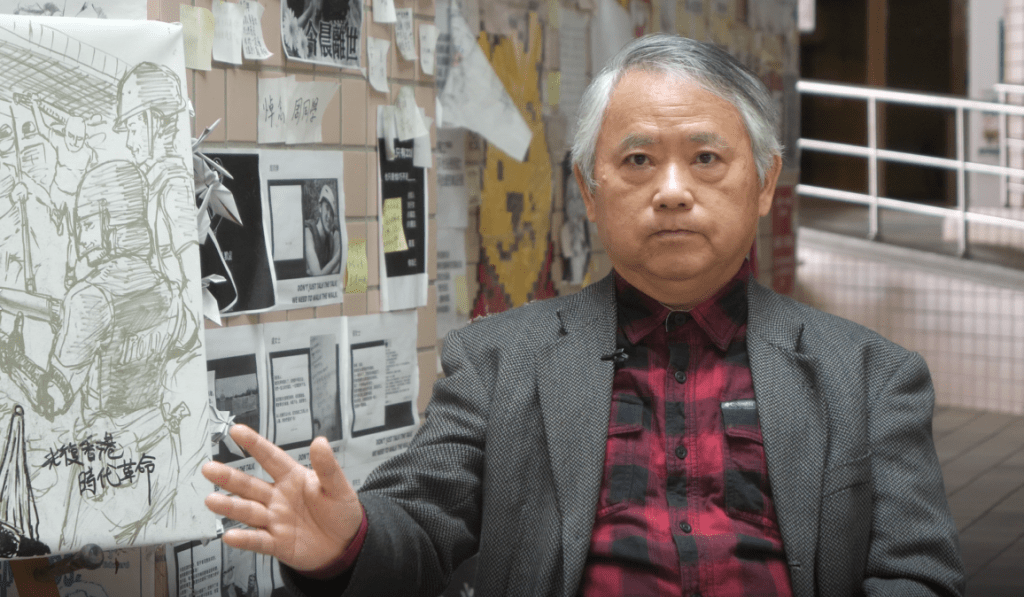

Chen Yen-Pin (陳彥斌) and his New Culture Association in Taichung have for years chronicled the Taiwanese struggle for freedom. In February 1980, Chen was serving in the army when Taiwan was shocked by the news that dissident Lin Yi-hsiung (林義雄)’s mother and two twin daughters were murdered at home and another daughter severely injured while Lin was on trial for his involvement in the Formosa Incident. The young Chen described how, in the garrison, he secretly read a newspaper describing the atrocity. Tears, dropping from his face, soaked the text. “What kind of government could be so cruel?”

On the wall of his office hung a picture of Cheng Nan-jung (鄭南榕, nicknamed Nylon). Every time his friend, a truck driver named Liao Jing-Chang (廖景昌), visited, he would make three deep bows in front of the picture, said Chen. After the interview, Mr. Chen took us to the old Taichung train station, and from there we strolled down Taiwan Boulevard, the route of the “New Nation Movement” (新國家運動) march that Cheng Nan-jung led in 1988 in Taichung and across Taiwan.

Also in Taichung, we spoke with Lin Fang Ru (林芳如), a young mother of two kids and the chairperson of Taichung Cosmopolitan Cultural Action (好民文化行動協會). The organization works in the community to boost citizens’ everyday participation in democracy. I asked her to write “a good country, a good people” on the chalkboard in the organization’s workshop. It came from one of Cheng Nan-jung’s writings: “We are a small country and a small people, but we are a good country and a good people.” Her handwriting, clean and upright, is as good as her person.

A Will to Victory

“Taiwan’s democracy is so young,” I said to myself time and time again on this trip. It’s an obvious fact but one that for the first time weighed on my mind, and with it, conjured the worry: Is it strong enough to endure?

Actually, the war on Taiwan has already begun. It has many components. One is deception. Mr. Ho Cheng-hui, the CEO of Kuma Academy, said, “Researchers around the world found that Taiwan has been the most targeted country of China’s cognitive warfare, or fake information, in recent years. Taiwanese society is filled with it.” The improbable story related at the beginning of a recent Atlantic article is by no means an isolated case.

The farce of “one country, two systems” has been politically bankrupt since the aftermath of the Hong Kong protests, but in Taiwan there has been a steady flow of public figures peddling different versions of it as a viable future for the island. For example, one retired Navy officer (not the one I met) recently proposed a “Chinese confederation system” that would turn Taiwan into a special zone of China that allows Taiwan to preserve democracy and even its own army. Such poor reasoning can hardly be a position argued in good faith; it looks more like something cooked up by the CCP’s overseas propaganda apparatus, of which I have seen examples in recent years.

Even Elon Musk joined the array of people repeating the CCP’s deceptions, suggesting that the “inevitable” conflict over Taiwan be resolved by absorbing it into the PRC by way of a “lenient” special administrative region.

Intimidation is another component. As reported, China has been steadily increasing its military menacing around Taiwan. It will not stop. This is as much a military threat as it is a main dimension of the CCP’s psychological warfare, working in tandem with the cognitive warfare inside Taiwanese society.

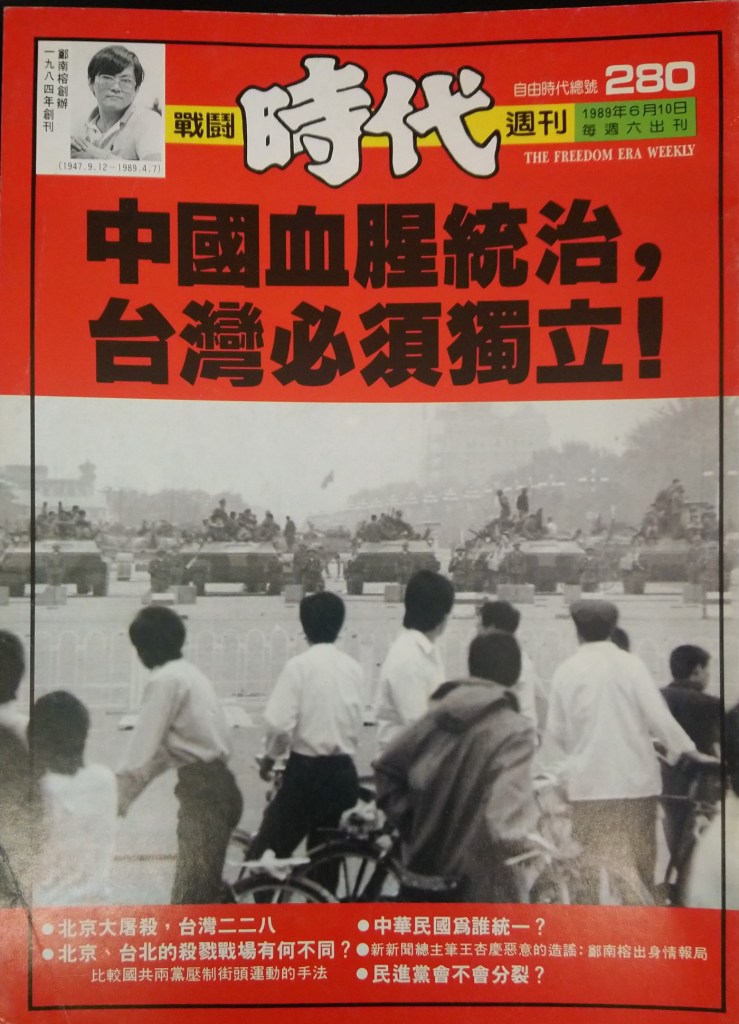

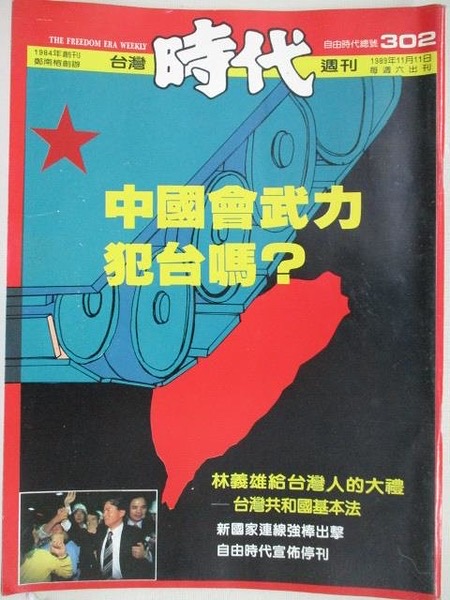

On the evening of the day of my departure, four hours before I headed to the airport, I made my last stop in Taiwan — the Cheng Nan-jung Memorial Museum. It is located in the old site of the Freedom Era Weekly magazine (《自由時代周刊》) that he edited, on the third floor of an apartment building on East Minquan Road. At the end of 1988, the magazine was outlawed for publishing “A Draft Constitution for the Republic of Taiwan” (《台灣共和國憲法草案》) authored by Koh Se-kai (許世楷, 1934–), a Taiwanese historian and politician. By January 1989, Cheng received a summons from the then Taiwan Supreme Court’s Prosecutors Office (台灣高等法院檢察署) for allegations of “insurrection.” He refused to appear in court to answer questions, protesting the government’s attempt to suppress the freedom of speech of the Taiwan independence movement. He locked himself in the chief editor’s office. “The KMT cannot arrest me; they can only get my dead body.”

After remaining in his office for 71 days, the police came. On April 7, 1989, when police were sawing the metal door to the apartment, Cheng doused himself in gasoline and set himself on fire. He was 41 years old. It was already nearly two years after Taiwan lifted the 38-year martial law. Cheng’s last words to the public were an article titled “Independence Is the Only Way for Taiwan to Survive”.

It was pouring outside. The chief editor’s office kept its original look. Cheng’s desk, objects on the desk and an ashtray, a camping bed, a sofa, a fax machine, everything was burned black and distorted. The window frames had turned to charcoal.

The lead officer of the policemen who came to arrest Cheng was Hou You-yi (侯友宜), the current mayor of New Taipei City and the favored KMT presidential candidate in 2024.

Taiwan’s democracy really is new. Less than one generation. The authoritarian era is barely over — those who ran the dictatorship are still around and its political networks still exist, as pointed out by Wu Jun Yen as he told me of the KMT’s remaining strongholds: “Did you know that there are many places in Taiwan where the DPP has never won any [executive] elections?”

The June 10th issue of the Freedom Era Weekly wrote in its editorial “Beijing Massacre, Taiwan 228”, “The blood-thirsty nature of the Chinese regime reminds Taiwanese people once again that [Taiwan] can never choose to be reunited with China, and can never accept its blood-thirsty rule.”

In the issue of November 11, 1989, the Freedom Era Weekly announced its closure with the cover story “Will China Carry Out a Military Attack on Taiwan?”. With regard to the definition of victory, author Dr. Robert Y. Lai (賴義雄博士) wrote: “Psychological warfare is of critical importance for Taiwan, and victory or defeat is up to the Taiwanese people. As long as we have the will to fight on and the confidence to defend our land, the enemy will not be able to crush our spirit.”

So true do these words ring in today’s Taiwan!

And since the elections, the term “Resist China, Defend Taiwan” has been met with casual scorns as well as deliberate denigration by some corners of Taiwanese society. Again, it can be debated and reviewed whether it was the best campaign platform in local elections, but as far as Taiwan’s future is concerned, it’s the ultimate test, more so than military weapons. Taipei-based Japanese journalist Yaita Akio wrote the other day: “‘Resist China, Defend Taiwan’ should be the most important responsibility of every politician in Taiwan.”

To this I would add: Taiwan is not the property of politicians, but belongs to the Taiwanese people. “Resist China, Defend Taiwan” should be the most basic consensus and determination of all Taiwanese.

Acknowledgements

I’m deeply indebted to two Taiwanese friends who made this trip a smooth and fruitful one. Without them there would be no interviews, and I’d have been a clueless tourist not knowing where and who to turn to.

I also wish to thank another group of Taiwanese friends whose thoughtful work provided me with valuable access to many offices, organizations, and fascinating people during this visit.

Comments are closed.