2022: Remember the Light the Young Have Shown Us

2022: Remember the Light the Young Have Shown Us

Jiang Xue, January 3, 2023

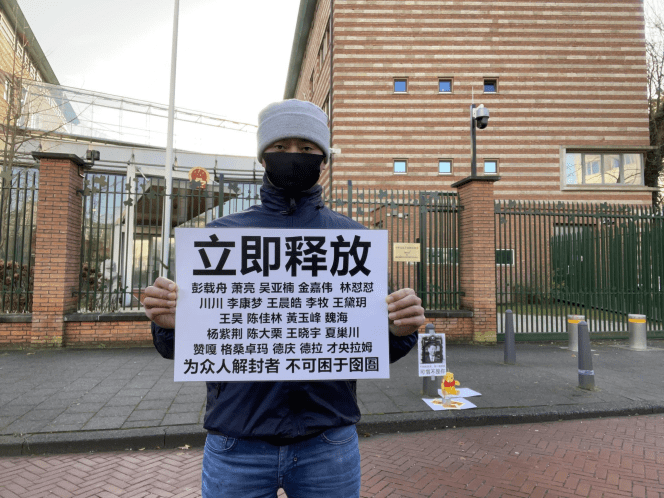

In Beijing, at least 11 young people have been detained in connection with the “Blank Paper” (白纸抗议) protests, of whom two are confirmed to be journalists, another two musicians, an editor, a curator, and a white-collar employee at a foreign company. The identities of the rest are still unclear. — The Editors

“Mom definitely knows I didn’t do anything wrong.”

Yes, young lady, of course. You are innocent.

It’s winter in the north, where temperatures can easily fall below zero. More than 100 kilometers away from Beijing, in the town of Pinggu located in the district of the same name (平谷区平谷镇), the trees are withered and leafless, but the sparrows hopped and chirped lively.

Lawyer Zheng paid you a visit in the detention center. The words above are what you told him as you said goodbye.

You asked the lawyer to tell your parents to take care of their health and eat more fruits. Do you know, sitting in jail, that as 2022 comes to its end everyone in China is suffering from coughs, fevers, sore throat, and shortness of breath? The “big whites”[1], who knocked on people’s doors in the middle of the night or broke in via windows to enforce COVID tests on the entire population, disappeared overnight without a trace.

Many people lie in their beds or struggle to leave their homes. They search desperately for common antipyretics and thermometers, and moan in pain. The pharmacies have been emptied; the hospital aisles are filled with beds. The nurses’ hands shake as they give injections. Doctors and nurses caught the virus before many of their patients did.

The dead are piling up across towns large and small; many more elderly will not make it past this winter. The mortuaries are packed, the living have nary a chance to say a proper farewell to the dead. The Chinese New Year, coming as always, only adds to the sad helplessness that fills our hearts. Even in your jail cell, you too are worrying about your parents’ health.

I don’t even know your name. The lawyer wants to protect you, so he can’t do anything that pisses off [the government], he can’t “hype” anything, your story cannot be told. But I know the rough version of who you are.

Are you that girl I once called? Were you with the girl standing by Liangma Bridge (亮马桥) in the middle of the night in Beijing on November 27, shouting out your inner voice from the bottom of your heart?

You might not know each other, you and her. But were you like her? You may have seen the news in the WeChat group, and headed out without hesitation just like her, thinking to yourself: “If I go out tonight and join the protest, it might be the day that changes my life” — these were the words the other girl told me.

Were you also like her, and, standing in the crowd, saw a girl from Xinjiang who was covered from head to toe? Did you also see how she trembled with fear, yet still managed to say, “I’m really scared. But I want you to pay attention to the people in my homeland” as she held a blank piece of paper and covered her tear-soaked face.

Just like the girl I talked to, did you also realize, at the moment when she stood by the roadside, that you had no idea what demands you were going to shout? Everyone showed up spontaneously, not instigated by any “force” or “organization” as the Party has claimed. So when someone asked: “What are your demands as you stand here?”, all the protesters were tongue-tied for a moment.

The other girl told me how, in Beijing that night, surrounded by so many police officers, protesters tried their best to keep their cool. Yet they still shouted a lot of the things that were on their minds. “Freedom of speech!” “To hell with film censorship!” “No more ‘404 page not found!’” Were you there with them?

The crowd burst into laughter when a young man shouted: “I want dine-in!” Then someone else yelled: “I want to eat hot pot!” “I want to eat McDonald’s!” Did you also hear their shouting, and laugh with the rest of the crowd?

Were you also, like her, surprised to find that in the end, the demands that you made were the same as that of the man who stood and shouted on Sitong Bridge a month and a half ago? And all your voices finally converged upon the loudest note: “Give me freedom or give me death!”

Yes, you did not ask for much. Your cries were only based on the fact that life had become unbearable.

Yes, everything you asked for was simply what should be part of a normal life. And precisely because it is a resistance based on the normal demands of life, it took on the power of infinite possibilities. Let those who hear these cries see you for the first time: the youth of our age.

“I’ve always felt like I haven’t lived up to my humanity. I haven’t dared to fight for anything. But from last night to now, I finally feel like a human being, acting as a human should.” This is what the girl who stood with you on the street told me.

I don’t know where she is now. But her voice has been echoing in my heart. I want to tell you and tell other people about this voice of hers.

Young lady behind bars, please stay strong. Your mom definitely knows you’re right. Those who live in humiliation, are ashamed of their cowardice, and blame themselves for not giving you a better world, those middle-aged people like me, all Chinese with a normal conscience, know that you are not wrong.

You are the most precious youth in this country. You are the shining diamonds. Your blood is hot, your hearts are sensitive. You have empathy for others, and deep compassion for the suffering of your compatriots. You cherish yourselves as individuals, not an abstraction in the collective, the -isms, and vapid, hollow concept of “the people” the Party claims to represent.

The bell of the new year has sounded. The sad year of 2022 is behind us.

In January, Xi’an (西安) was under lockdown. In February, the mother of eight in iron chains screamed out to the world. In March, a plane crashed [in Guangxi]. In April, we heard the cries from Shanghai. In the following months, Beijingese got Covid pop-up windows that stopped them in tracks, and in a restaurant in Tangshan a group of young women were savagely beaten by thugs on camera. A father who broke through the quarantine barriers to buy medicine for his child, the girl who was tied up in the street for picking up takeout at a street corner, and the three-year-old boy in Lanzhou who died after being denied emergency care under the lockdown, they are us, the humiliated, the damaged, and the tormented.

In September, a bus [in Guizhou] flipped over and took its passengers off a cliff. In October, a man’s call on a bridge in Beijing reverberated across China and around the world. In November, in Urumqi, which had been locked down for more than 100 days, a fire in a residential building engulfed many lives and awoke countless Chinese nationwide.

You stood in Shanghai, in Beijing, in Chengdu, in Guangzhou, in Nanjing; in the east, west, north, and south; on college-campuses-turned-prisons, on the bustling Wulumuqi Central Road (乌鲁木齐中路), at the front gates of many locked-down residential communities. You held flowers, candles, and sheets of white paper. You, the youth of this country, had had enough and made your voices heard.

Now, 2023 has arrived. For the first time in many years, our loved ones are struggling to say “Happy New Year” under the torment of illness and pain.

Right now, it seems that we are sunken in the abyss of a dark night, but people are forgetting that this winter, we had you. Even though you, having committed no crime, are detained, interrogated, and imprisoned, your stories, your youthful figures in the street at night, your swaying arms and flowers, and blank papers of protest, have shined a glimmer of light into this dreary iron cell that is China!

On New Year’s Day in 1990, the writer and then newly-elected President of Czechoslovakia Václav Havel said in his New Year’s Address to the Nation: “And let us ask: Where did the young people who never knew another system get their desire for truth, their love of free thought, their political ideas, their civic courage and civic prudence?”

In November 2022, you are those young people. Because of you, the suffering that the people have endured over the past three years of the pandemic dictatorship has taken on some meaning. It is by speaking out loud and clear what is in your hearts that you have won a little dignity for the beaten-down and enslaved masses.

Also because of you, on the first day of 2023, when the sun rises, we can still say with hope: Happy New Year! We look forward to your safe return.

[1]大白, a nickname for the epidemic prevention personnel inspired their full-body hazmat suits.

Jiang Xue (江雪) is an independent journalist in China, and the author of “Ten Days in Xi’an” (長安十日), an account of the month-long “zero-COVID” lockdown in Xi’an starting late 2021, the first major city lockdown since Wuhan in early 2020.

Translated by China Change from 江雪:2022 – 记住青年带来的光亮 .

Comments are closed.