‘I Don’t Want You in My Navy’– Forging My Own Path to Those Silver Eagles

I was born in 1960, and if I had been born in ’58,

it would have been a completely different life.

— Michele Howard, Admiral, U.S. Navy (Retired), first woman four-star admiral and first Black woman to captain a U.S. Navy ship, Women in the Arts, Fall 2020

“You’re a piss-poor O.C. You’ll be a piss-poor officer.” The lieutenant rubbed his paunchy belly as if chewing me out satisfied him viscerally. He pounded on the WWII-era gray typist desk, which thankfully stood between us. “It’ll be 1980 in a few months, but everything is still about women’s lib, and power to the people, and Z-grams.”

I stood at attention, a posture learned only a month ago. I winced when he moved toward me. Was he going to hit me?

The lieutenant took a deep breath. “I don’t give a fig about any of that. You. I don’t want. You. In my Navy.”

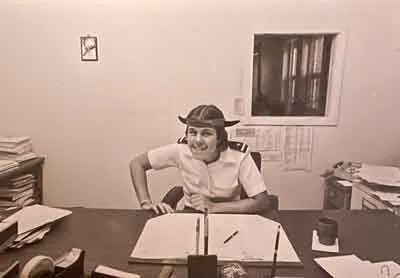

Ensign Van just before her commissioning at Naval Education and Training Command, Newport, Rhode Island, in December 1979. Black duct tape covered the single gold stripe of an ensign to indicate officer candidate status. Photo courtesy of the author.

I stared straight ahead and, out of habit, my teeth grabbed a chunk of my cheek and bit down. The movement and pain forced me to focus and be still, a technique carried over from being the youngest of three in a rough-and-tumble neighborhood. What was the lieutenant yelling about this time? The women’s rights movement I knew about, but Z-grams would only be revealed in subsequent lessons as the platform for then-Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Zumwalt’s overhaul of the Navy’s personnel and manning policies.

This quality time with the company officer was not the uplifting, rah-rah speech you might expect from someone whose charge it was to encourage and develop the U.S. Navy’s next generation of officers. Check in as a civilian at Newport, Rhode Island, the Navy’s accession school for line and medical officers, and check out as a junior officer in the sea service. Ninety-day wonders. Veritable gifts to the fleet.

Yet here I was again in my company commander’s utility closet/office, a space as ratty and offensive as his person, as he again pressured me to quit. It seemed like the universe’s forces were against me becoming a naval officer. While the lieutenant didn’t use names I’d heard females referred to before, his derogatory tirades left no room for any other conclusion.

The lieutenant had a point. My performance had been mediocre across the board: in the classroom, on the marching field, and on the physical fitness tests. I did not hold a leadership position. I bristled at the capricious treatment by those only a few weeks senior to me who, in their roles as class officers or squad leaders, had us “cherries” fall out in the hall for lectures or inspections of our rooms or uniforms, or for no reason at all.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

I cringed, remembering my most recent screwup. I was plotting the stars on the chart for the celestial navigation exam. The instructor, a master chief and quartermaster with 30-some years navigating vessels by the stars and the horizon, put his ham-sized hand on the multicolored paper that covered my desk and chortled, “Officer Candidate Van, it might help if you had the chart right side up.”

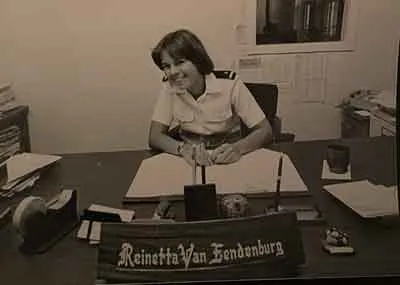

Ensign Van at her desk at Naval Station Guam in 1980. During Officer Candidate School, Van’s company commander told her she didn’t belong in the Navy. Van went on to serve for more than 30 years. Photo courtesy of the author.

I gulped out a “Thank you, Master Chief.” I keep the navigation tools as mementos of when I viewed things upside down, and of the compassion of others who kindly corrected my perspective.

I joined the military because the 1970s recession limited career opportunities for college graduates, especially from liberal arts colleges like mine. Along with other seniors at Allegheny College, I interviewed with a variety of headhunters who visited the verdant campus in northwest Pennsylvania.

The General Motors recruiter and I hit it off. He enjoyed my anecdotes about summer stints on the Ford Motor Company’s Mahwah, New Jersey, assembly line, especially the insider jokes about disgruntled employees throwing nuts or bolts into semiformed chassis or management speeding up the line when they thought the union rep wasn’t looking and they could get away with it. He said I’d be a good fit for a position based out of the Detroit headquarters. I would drive a van across America, giving canned presentations to schoolchildren about the wonders of the auto industry. GM’s world view.

While I liked the idea of touring the country, I didn’t like the job. It lacked substance. I wanted something more, without fluff, but that was the only spot he offered. The General Motors recruiter insisted it was a public relations position perfect for a perky young girl like me. He wouldn’t take no for an answer and continued to call me while I trained to become a naval officer.

My stint as part of Officer Candidate Class 1979 at Newport, Rhode Island, spanned a sweaty August to a frigid December. The short autumn was overshadowed by physical conditioning, as my knees swelled due to the incessant trudging on pavement and I moved peg-legged like Charlie Chaplin. Then a squad leader yelled in my ear to punch out more sit-ups to raise November Company’s competitive standing, which led to three days in sick bay with a pulled back muscle, one that has never really recovered.

Ensign Van in white gloves, reminiscent of the “Old Navy.” She joined the military in 1979 because the recession left her with limited career opportunities. Photo courtesy of the author.

My roommate sailed through OCS, as those coming from the fleet familiar with the material do—especially those who are tall, blond, and wicked smart. This was fun for her, and she tried to get me to lighten up. I appreciated her levity, but I had to double down on the memorization of pay grades, Navy terminology, and ship’s boiler systems. I did not want to drop any tests that might turn into more ammunition for the lieutenant’s shots.

We were all volunteers since the draft had ended in 1973, and we could leave the training at any time. A few men had already dropped out of our company for jobs too tempting to ignore. I also was in a quandary. I questioned choosing the Navy’s restrictive environment where I apparently showed little aptitude for success. Although the auto maker’s salary and benefits were lower than the military’s, GM did want me.

I distinctly remember one orientation parade, the nippy chill of the New England afternoon biting through my black poly-wool jacket and skirt. The thin cotton shirt did little to add warmth. The November Company leadership had cautioned the women in the unit to ensure that our “split-tails were neatly trimmed,” an ostensible reference to the black ribbon that overlapped at the back of our bucket-shaped hats, forming a “V.” We checked the ribbons on each other’s hats: ready for inspection.

All of us, however, had black duct tape indicating our training status covering the gold braid on our suit sleeves. We were in formation, about three hundred officer candidates, all in service dress blue suits, standing on our square pieces of real estate on the grassy parade grounds.

The commandant of the Officer Candidate Corps spoke from the parade box. November Company was too far back in the ranks for me to see the captain, but his measured, sonorous voice rolled over me as I shifted from left foot to right foot, hands clasped behind my back. I don’t remember the gist of his speech.

Ensign Van in 1980 at Naval Station Guam, where she worked as an administrative officer. Photo courtesy of the author.

This was what hit home that autumn day: There were as many paths to captain as captains. Was that my goal? As my feet froze on the cold Newport ground, truly I just wanted to make it to ensign. Yes, “go for the gold” does not just refer to sports. Every officer candidate had an equal shot of wearing those coveted silver eagles because the multitude of variables—training opportunities, personal attributes, and even plain old luck—leveled the odds. Maybe three or four of those officer candidates would pin on the captain’s pay grade of O-6 some 20 years down the road. My chances of success were as good as anybody else’s.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

I’m glad I didn’t know how naive that thinking was.

My company commander failed as a commissioned officer. As a washed-out lieutenant, he was now just marking time to leave the Navy. Who was he to judge me? While he did not see any potential in me as an officer, he had no right to stop me from trying.

Lesson learned.

Comments are closed.