Hutong, DJ Bars, Youth, and Unexpected Politics: The Detained Blank Paper Protesters of Beijing

Hutong, DJ Bars, Youth, and Unexpected Politics: The Detained Blank Paper Protesters of Beijing

Su Nian, February 18, 2023

Based the information we have able to gather so far about the protest that occurred in Liangmaqiao (亮马桥), Beijing, on November 27, 2022. It seems that the Chinese police have set their eyes mostly on two groups of people: a circle of young women and a small community of DJ bar owners and musicians. We’ve since learned more about the former, but little about the latter. Nor do we have a precise idea how many have been formally arrested in Beijing and elsewhere. This article by a Chinese journalist (Su Nian is a new pen name she’s adopted) is a much-needed attempt to understand the young protesters beyond their names and jobs: who they are, how they feel and think, and what their lives are like. The translation that follows is a trimmed version of the Chinese original. — The Editors

On the morning of January 20, the day before Lunar New Year’s Eve, 27-year-old Cao Zhixin (曹芷馨) met her lawyer for the first time after being detained for twenty-nine days. In the meeting room of Beijing’s Chaoyang District (朝阳区) Detention Center, she wore the facility’s winter inmate uniforms —a khaki coat and padded gray pants.

Two days prior, some time after 11 p.m., a number of participants in the “memorial activity at Liangma river” (亮马河) being held in the detention center were released on bail. Among them were journalists Yang Liu (杨柳) and Qin Ziyi (秦梓奕), but not Cao, an editor at Peking University Press. Meanwhile, she and some close peers — Li Yuanjing (李元婧), Zhai Dengrui (翟登蕊), and Li Siqi (李思琪) — were formally arrested. Their charges were changed from “gathering a crowd to disrupt public order” (聚众扰乱公共场所秩序) to “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” (寻衅滋事).

Cao Zhixin was crushed by the news of her formal arrest. The idea that she would end up in jail for taking part in a mere memorial activity was difficult to digest. When the lawyer brought greetings from her family and boyfriend, Zhixin couldn’t hold back her tears.

She didn’t know, before seeing the lawyer, that the video she’d recorded before her arrest and had been released after her arrest had reached a worldwide audience. In it, she related a premonition about what might happen to her and others at the protest scene: “All we young people did was mourn our fellow Chinese. Why do we have to pay the price of being disappeared?” “What are the qualifications of the people arresting us?”

Both her lawyer’s application for bail and written opinion arguing against her arrest had been turned down.

Another young lady arrested on the same day as Zhixin — 27-year-old Zhai Dengrui — was not able to meet with her lawyer ahead of the Lunar New Year due to complicated legal procedures and a raft of unexpected hurdles.

She had been in the process of applying to a theater program at the University of Oslo, but now she has missed the application deadline.

Li Yuanjing is a Nankai University graduate who became an accountant after finishing her studies in Australia; she’s also the “wealthiest” of the young female detainees. Li Siqi is an avid reader and writer who calls herself the “unfree author.” She is a graduate of Goldsmiths, University of London, which on January 31 published a statement of support for its alumna.

The four of them are close friends who lived in the same hutong community in Gulou, or the Drum Tower, part of Beijing’s ancient city limits. They share that distinct temperament of literary youth — love of reading, writing, attending film screenings, and underground music — and they are drawn to places with a distinct quality of rebelliousness on the margins of the capital city’s mainstream culture.

They are passionate about social issues, but have hardly made their debut when it comes to making their voices heard in public. A close friend described Cao Zhixin and her friends as mostly being “semi-activists,” a group of young people who love life, are “interested in everything,” and are willing to try everything. “But they still have a considerable distance from the really hard questions.”

All of them began college around 2015. Chinese civil society, having blossomed for over a decade, was already beginning to wane under renewed crackdowns, and has only come under greater pressure since. Countless public forums of various sorts have vanished over the past decade. But in Beijing, a city that has long boasted a rich literary and artistic scene, these four women, as well as many like them, came of age in what little of the nascent civil society that has persisted, remained, and evolved, bearing a particular generational imprint.

“All of this was bound to happen sooner or later,” said their friend Ah Tian (阿田), who left Beijing for another city in the fall to pursue a Ph.D degree in anthropology “The extreme COVID policy of the past three years was only one trigger. In China, as long as there is injustice, there is certain to be resistance.”

“Given time, they would be able to shoulder more. But now, as they face severe punishment for just one street protest, the beginning seems to be the end,” he lamented.

The arrests

On the night of November 27, Zhixin and some friends saw the news on the internet mourning the victims of the Urumqi fire, so they went to Liangmaqiao, which was not far from where they lived. Zhixin posted in her WeChat friend group two photos: a bouquet of flowers she had brought and her hand-copied poetic verses, as well as young people on the scene.

It was quite late when they left. Zhixin and her friends went to a bar near the Drum Tower, and didn’t return home until early morning. Her good friend Zhai Dengrui slept at her place, waking up late the next day. At around 11 a.m. on November 29, Zhixin was in a phone call with her boyfriend when the police arrived. He could hear loud voices on the other end as the officers entered her room.

She was taken to the nearby Jiaodaokou (交道口) Police Station and released in the early morning of the next day. But the police station confiscated her mobile phone, computer, and iPad.

On December 7th, 10 days after the Liangmaqiao event, the Chinese government announced its “New Ten Measures,” relaxing the zero-COVID policy overnight. The coronavirus swept across the country like a tsunami: essential drugs were in short supply, hospitals were overrun, and funeral facilities couldn’t cremate bodies fast enough.

Zhixin got infected too, as did everyone else she knew.

But when all was said and done, the harsh and absurd zero-COVID lockdowns were no more. Cao Zhixin and her friends became more optimistic. In any case, the government’s loosening of control is an indirect admission of the failure of lockdowns, which in turn seems to vindicate the protests in Liangmaqiao and across the country.

“We estimated that there was a 50 percent possibility that this matter would just pass without incident, after all, everyone just went and expressed their normal condolences. But there was also a 40 percent possibility that people who went to the scene might be given several days of administrative detention. We placed the chance of serious consequences at 10 percent,” a friend of Cao’s said.

But the worst and the least likely scenario occurred. During the live broadcast of the Qatar World Cup final on December 18 when half of the country was glued to the TV screen in excitement, Cao Zhixing and her boyfriend included. Halfway into the match, she got news that several of her friends who had gone to the protest were detained. A shiver ran down her spine.

“That night, as the crowds celebrated Lionel Messi’s win in the World Cup, our hearts were frozen with dread.” Her boyfriend said. It was a strange and unforgettable night.

The next day, Cao Zhixin took the train back to her hometown in Hengyang (衡阳), Hunan province. “She felt that this way, even if she was arrested, she would at least be with her family when it happened,” a friend recalls.

One day during her five days at her parents’ home, Zhixin secretly recorded a video, the one that has been widely covered in international news, to be released by friends in the event of her re-arrest.

On December 23, near noon, five or six police officers from Beijing knocked on Zhixin’s door in Hengyang and took her away.

‘Interesting youth’ and ‘semi-activists’ living in hutongs

Zhixin was first detained in the Pinggu District (平谷区) Detention Center, and then transferred to the Chaoyang Detention Center on January 4, 2023. Soon, the landlord called her relatives back in Hengyang, asking to have her terminate the rental contract and move out. Her friends helped move her things, mostly books and everyday household items, out of her former residence in No. 1 Dongwang Hutong (东旺胡同1号)[1].

After graduating from Renmin University in July, 2021, with a master degree in history, Zhixin rented one-room apartments in traditional hutong quadrangles near the Drum Tower area, north of the Imperial Palace on the central axis of the inner city. She likes the banausic feel of the hutong and didn’t care so much about its lack of modern amenities. As friends say, she likes Beijing more than the Pekingnese themselves.

While her boyfriend went abroad to continue his studies, Zhixin took up a job at Peking University Press after several internships at various publishing houses. For her, an avid reader and fledgling writer, it was a dream job.

She grew up in a family of civil servants, her parents working in the government system. But in the end, her reading and experiences away from home gradually turned this girl into someone her relatives didn’t really understand.

Her boyfriend is on the opposite side of the world, but that hasn’t kept them apart. They made daily video calls, but sometimes they simply did so to keep each other company while each doing their work. Other times Zhixin played ukulele and sang. He’s very much in love with her and believes that once they unite, they will discuss marriage.

On the night of November 26, a few hundreds of Shanghainese gathered on a section of the city’s Urumqi Road (乌鲁木齐中路) in the heart of the city for a vigil to commemorate the dead of the Urumqi fire and protest the unreasonable lockdowns, which the Shanghainese had experienced in last spring. The Liangmaqiao protest scene the next day had an optimistic and electrifying vibe. Many people who went to the scene didn’t even bother to wear masks.

Before, Zhixin and her friends hadn’t been involved in any activities that could be construed as “political,” nor had they really opposed anything politically. Many of them had never spoken out about anything publicly. As a result they have left little footprint in public.

Like Cao Zhixin, these friends of hers mostly live in or around the hutong communities. “Not many young people like to live in these shabby hutong apartments that have no indoor toilets, among renters working as couriers and doing takeout deliveries. But they are willing to live this way,” a friend Peng Peng (alias) said.

“Basically all my friends have this quality: they are happy to take small actions of resistance in their everyday life.” Most of these revolve around gender identity issues and various day-to-day injustices.

The things she and her friends like to do together, such as film screenings and book club discussions focused on issues such as women, the environment, and family, are not taboo topics in China. They are at best “semi-activists” in the opinion of Zhixin’s boyfriend.

This circle of young women, who graduated from university a little over two years ago, has come together just over a year ago, but now it’s squarely on the radar of the Beijing police. On January 6, 2023, Zhixin’s friend Cao Yuan (曹原), also an alumna of the Renmin University who majored in sociology, was taken away by the police.

Liangmaqiao, the site of the protest, had long been popular with the youth. The Liangma river used to be seriously polluted, but it was transformed into a very pleasant urban park by 2019. Moreover, this area is also the embassy district, with diverse cultures, food from all over the world — Middle Eastern, North African, or Indian cuisine, to name a few — attracting many experience-seeking young people.

However, the beautification of the cityscape can hardly conceal the increasingly oppressive political atmosphere. In media and academia alike, a wide-range of topics has gradually disappeared from public discussion, and the three years of COVID restrictions have only made it worse. As a friend of this circle pointed out, people would talk each time they held a gathering or a screening event, but tended to leave everyone dejected, as they “didn’t know what to do about it after the discussion.”

DJ bars and underground music

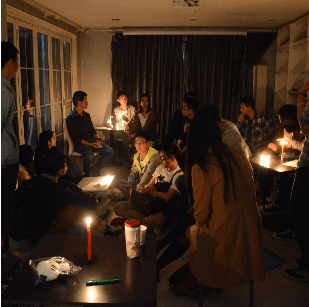

“706 Youth Space” was located in an apartment on the 20th floor of a residential building in Wudaokou, northwest of Beijing. One of the rooms was converted to a library. On May 11, 2018, young people packed the small room to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Mai 68 student protests in France

They read articles and poems aloud. On a black T-shirt hanging on the wall, the white lettering reads, “In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni” (“We go round and round in the night, consumed by fire”), the title of Guy Debord’s 1978 film.

“706 Youth Space” was an utopian autonomous space launched in 2012. Met with a myriad of difficulties, it’s barely hanging on today. It was a place where young people met to read, discuss ideas and life, and make friends. Qin Ziyi (秦梓奕) was also at that event in May and would become friends with some of the participants. It was also where Zhai Dengrui and Li Siqi met and became friends. “The young people at 706 were very sensitive to all forms of social injustice and inequality,” Peng Pengwas one of its frequenters.

But in 2012, the year Peng Peng arrived in Beijing for college, Xi Jinping’s “New Era” had begun. What used to be vibrant spaces such as independent bookstores as well as online and offline forums, propelled by the emergence of the Internet, came under systematic suppression and slowly died out, and newer places like the 706 Youth Space have had a hard time just getting by.

Young people also like to frequent some small DJ bars with underground music performances and live houses, or live music clubs. Cao Zhixin is one of them. She likes traditional folk songs, including New Pants band and Zhang Xuan’s (张悬) songs. “She also likes underground music, but not the most radical kind,” said her boyfriend.

One of those bars Peng Peng and his friends frequented was called “Pause” (暂停) in a hutong. The bar no longer exists. It was less than 10 square meters in size, probably the tiniest bar in the world. It was mostly frequented by “progressive” young people. In 2018, when a group of Peking University’s self-proclaimed Marxist students went south to support workers’ strikes at Jasic Co., a maker of welding products in Shenzhen and got arrested, it made an impact on many young people in these bars.

Peng Peng remembers those cold nights. The bar was too small, a lot of them had to stand outside in the cold, and the bar had on hand old-fashioned military overcoats for customers to wear during their wait.

The bar often hosted “plain,” a cappella performances. A music group named Kaleidoscope sang in the dark during a night of power outage. Another time, they sang on a roof in the hutong. The bright wintry sun was glaring, the wind hollowing, and they sang until nightfall and had to wrap themselves up in blankets to stay warm.

In the heart of the city but on the margins of its cultural life, these self-proclaimed “cheap and amateur” bars attracted musicians, artists, and young audiences, served as public spaces for them to come together, indulge their free spirits, and find like-minded friends under the increasingly invasive surveillance state.

“Running a bar business wasn’t exactly our dream job. As I said before, it was a journey to find ourselves, an idealistic experiment that offered what society couldn’t,” one bar owner once said. “Our bar seems like an utopia that attracts good comrades.”

Another bar that opened in 2019 folded after selling the 2019th order. There have been a lot of these idiosyncratic bars in Beijing.

Bars aside, in the Drum Tower (鼓樓) area of Beijing where Cao Zhixin and her friends like, other musical venues featuring small-scale performances can be found in a grid formed by a few streets and many hutongs, from the Avenue Outside the Gate if Earthly Peace ( 地安门外大街) on the west, to Dong Si (东四) on southeast, to Lama Temple (雍和宫) on the north, within the second belt ring road. This area is also the home of many video media production companies, publishing houses, and the Central Academy of Drama (中央戏剧学院).

“At least during the decade from 2005 to 2015, this area was the heart of independent music and live performances in Beijing, attracting the best known independent musicians, and young people came for its hip and fresh sounds,” a 2017 article reads.

In 2017, Beijing mopped up many exotic venues in the hutongs during the crackdown on the “low-end population.” And during the three years of coronavirus lockdowns, many people have left, leading to the slow disappearance of these venues.

Among the protesters arrested for the blank paper protest at Liangmaqiao are at least several musicians, bar owners, and DJs of whose circumstances we know very little. One of them is Lin Jun (林昀), a musician and boyfriend of Yang Liu. The number could be much higher, reaching over 100 across the country per an estimate by Chinese Human Rights Defenders, but we wouldn’t know who they are if their family members and friends are not speaking up, and have not signed up independent lawyers for them.

Engagement with society

“Of the arrested young women, many hold feminist beliefs, but their concerns are not limited to feminism,” said Ah Tian. “They are Good Samaritans who would take action to counter injustices.” In this sense, he thinks they are activists. Zhai Dengrui (翟登蕊, nicknamed Dengdeng), for example, was in several WeChat groups that focused on the COVID lockdowns.

Dengrui is from a well-to-do family in Baiyin, Gansu province (甘肃白银), studied at Fujian Normal University for undergraduate, and went on to get a master degree in comparative literature and world literature at Beijing Foreign Language University. Before her arrest, she was an instructor at an online extracurricular school. The government cracked down on online course providers in the name of alleviating students’ burden in 2021, she tried livestream e-commerce selling supplementary school books. His friend Li Siqi, who has also been arrested, wrote about Dengdeng’s e-commerce job and was abhorred by the slavish workplace conditions, but Dengdeng decided to treat it as a field study of Chinese parents.

Ah Tian said that all of his friends came from middle-class families, and their parents either work “in the system” — either in the government or in state-run entities. It’s been difficult to contact them after the arrests, and most parents chose to “trust the government.” This shows, said Ah Tian, that “they have had limited communication with their relatives.”

Ah Tian remembered that after the Lunar New Year in 2022, he contacted a few friends who were studying social sciences and planned a trip to investigate some non-ferrous metal mines in southern China. They decided to go to several mines in Chenzhou, Hunan (湖南郴州). With them was Cao Zhixin, who is from Hunan.

“She really cares about the environment,” said Ah Tian of Cao Zhixin who studied environmental history. They talked about the difference between these non-ferrous metal mines in southern China and the coal mines in the north, and concluded that the coal mines in the north can at least bring benefits to the local farmers, while the non-ferrous metal mines in the south are all state-owned mines, and the local people receive little benefit.

They wanted to study those underdeveloped parts of south-central China, taking into account the combined historical, geographical, and environmental factors. In this kind of exploratory fieldwork, Ah Tian discovered that Cao Zhixin had a knack for conducting good interviews. “She did this out of simple curiosity and genuine concern for society.”

They visited a uranium mine and found a village of widows. In this community, all the miners in the first-generation “prospecting team” died of silicosis. After they fell ill, they were relegated to the lowest level of urban commoners. Ah Tian remarked that “average people wouldn’t pay any heed to the dark happenings in their home provinces, but she [Zhixin] went.”

The way Ah Tian sees it, there are too many problems in China, and his friends, including Cao Zhixin, Qin Ziyi, and Zhai Dengrui, are all acutely aware of them. Some of these friends want to draw attention through news reporting. In his eyes, these friends are so young and enthusiastic, not afraid of dipping their toes in activism. By doing so, they also felt they were empowering themselves.

“Growing up, they were all good students by the conceived standard, well insulated from broader society,” Ah Tian said, and they could have reinforced that insulation by pursuing, say, academic careers. However, a force compelled some of them to do field research and others to take part in volunteer causes. For example, a friend of Ah Tian went to a nursing home to interview elderly during the Shanghai COVID lockdown, and produced a first-hand account of what she had seen.

“Once you start paying attention to social issues, you will quickly find like-minded friends. Through writings and other means, they become connected.” In Beijing, there were relatively more opportunities for such interactions, and a common theme running through them was “social ills.”

Ah Tian observed that for their generation, even though the 1989 movement was earth-shattering, it was not their own lived experience. Today’s young people, when standing up for their causes, aren’t motivated by any particular ideology but a simple sense of justice, a feeling sufficient to overcome their fear. “They are able to overcome societal indifference, and not easily cowed. But at the same time, they are also very inexperienced.”

However, their friend Ah Tian believes that they are defined more by a subcultural quality than outright social and political activism. “All of these are not contradictory. After all, the majority of young people [in China] don’t pay close attention to social issues. When they do end up doing something, it often happens on the spur of the moment.”

“In today’s China,” he continued, “whatever you do, you are met with suppression. But people inevitably fight back as long as there are injustices. When you start asking yourselves, why is China such a cruel place? You would want to do something about it.”

‘The lockdowns are not too different from a war’

In late fall of 2022, this band of young friends got together once. Some had not seen each other for a long time.

But a deep-rooted sense of depression trumped the joy of seeing one another. The zero-COVID policy, begun in early 2020, had become more severe going into 2022. Months-long lockdowns spread from Xi’an to Shanghai, then across the rest of China. Everyone took the compulsory PCR test on a daily basis. Once on a cold, snowy day, Li Yuanjing stood in line for four hours to take the test.

It’s absurd, they all agreed, but there was nothing they could do. They also discussed about “run” (润), or leaving China, the current fad among Chinese. They couldn’t take it anymore.

For criticizing the COVID policy on Weibo, Yang Liu, a journalist with the Beijing News (《新京报》), was threatened by her landlord who in turn had received a visit from the cyber police.

The daily barrage of absurd and tragic stories during the lockdowns offended the sensibilities of these young people. When one of their friends in Beijing, a former Yugoslav who had lived through the civil war in the 1990s, said the lockdowns in China were no different than a war, they had an epiphany: They were in fact refugees in a war without smoke.

Xiaoyi (alias) misses her friends in the detention center. Li Yuanjing (李元婧), who is considered the least politically-inclined, “got arrested simply because she was the administrator of the Telegram group where the band of young women socialized.” When they went to Liangmaqiao that evening, they had a lot of passion to dispense, and were unprepared for the political consequences.

The Lunar New Year is over. Some detainees have seen their lawyers, others have never been heard from.

Bu Er Bar (不二酒馆) has re-opened, but nowhere are the friends who used to come, nor its founder Lin Jun and his girlfriend Yang Liu. But its little chalkboard has been retrieved. On it is a stanza from Bei Dao’s (北岛) poem “A Rainy Night” (雨夜):

Even if tomorrow at dawn

I face the muzzle of a gun under the blood-red sun

Robbing me of my freedom, youth, and writer’s pen

But never will I surrender this night of mine

[1] A hutong (胡同) is a traditional form of neighborhood common in Beijing and other cities of northern China. They are known for their narrow alleyways and enclosed courtyards.

Related:

2022: Remember the Light the Young Have Shown Us, Jiang Xue, January 3, 2023.

Comments are closed.