Banning My Son From Doodling A Gun Is Not A Solution To School Shootings

What is it that makes a little boy — practically straight out of the womb — take an interest in weapons and emulate gun-toting, swash-buckling heroes? Even doctors aren’t sure. As one pediatrician told me about my then 16-month-old son who turned every stick into a sword, “We don’t know why. They just do it.”

If you’ve raised a little boy, you know what I’m talking about. And the only thing more predictable than them being fascinated with weapons is them eventually doodling one in class. An alien with a laser gun. An elf with a sword. Rambo with a machine gun.

When they do, they’ll encounter a host of school polices banning images of weapons, ostensibly to prevent school shootings and other violence. Some make exceptions for historical context (such as a Revolutionary War soldier with a bayonet).

Others don’t. Who can forget the infamous Pop-Tart gun of 2016? The 7-year-old was suspended.

If your child is lucky, he’ll be told to put the drawing away. If he’s unlucky, he’ll be sent to the principal’s office and then to the school counselor, where he may even be given a suicide assessment.

No Drawings with Guns Allowed

My first encounter with this type of policy was when my youngest boy came home from a Fairfax County, Virginia, elementary school with his shirt inside out. On the front was an image of a Lego Ewok holding — eek! — a tiny axe.

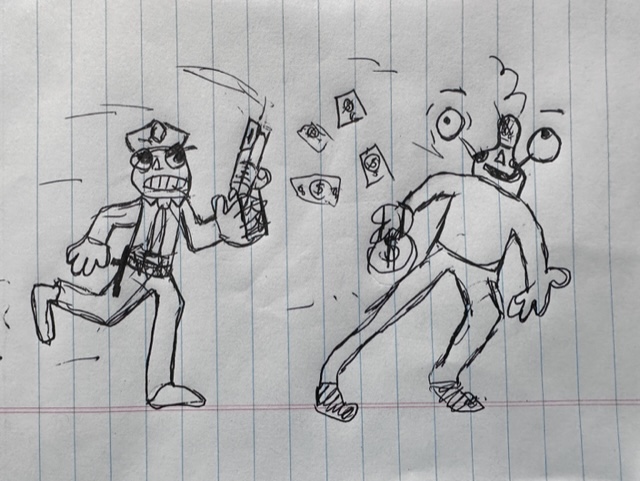

I recently encountered this policy again with my 10-year-old son. He had gotten in trouble for drawing a police officer holding a gun. A police officer.

In an email, my son’s teacher said she explained to him that drawing weapons in class is not allowed and encouraged him to “stick to dragons and landscapes.”

My heart goes out to my son’s teacher, and to every teacher, who has to worry about one of their students bringing a weapon to class. But I was honest: I have no problem with my son drawing a police officer with a gun, an alien with a gun, or pretty much any other living creature holding a gun. Bugs Bunny once pointed a gun at Nasty Canasta. I’m fine with that, too.

My son’s interest in guns is not a violent one because he’s not a violent boy. He’s a peacemaker — an empathetic child who cares for animals and respects teachers. He’s shot real guns under the supervision of responsible, trained adults. His grandfather was a cop, which is why he sees them as heroes.

But the fact remains: He’s a boy, and boys have been drawing weapons for hundreds of years.

Part of the thinking behind forbidding gun imagery, I gather, is that if a boy takes an interest in guns, he’ll take an interest in bringing a gun to school and killing people with it.

Signs of Mental Illness?

Schools must enforce the thinking of our increasingly leftist-controlled culture, which paints gun usage as only negative. There is no sporting use. No self-defense use. No stopping-the-bad-guys use. Were guns a moral good when they stopped Hitler from marching millions more into the gas chambers? I think so.

Perhaps the thinking behind the “no gun imagery” rule is that fellow students will look at the drawing and fear the child is the next Nikolas Cruz, thus creating an uncomfortable learning environment.

If the child is mentally ill and has the intent to do harm, wouldn’t the drawing provide important and life-saving insight into his mental state? And wouldn’t he draw it anyway, regardless of your policy? Ethan Crumbley, who killed four fellow students at his Michigan high school, wasn’t drawing cops or cowboys. The blood-soaked images he drew were surrounded by clear red flags: “My life is useless.” “Blood everywhere.” “The thoughts won’t stop, help me.”

The second and more likely possibility: The child is not mentally ill and is drawn, in true male fashion, to the gun-toting (or tiny axe-holding) hero archetype. If it scares the teacher and fellow students to see a doodle like this, they are inferring something about the nature of males that is incorrect: that aggression and strength can never be harnessed for good.

A gun is a neutral extension of the person holding it. It can bring peace and restore justice, or it can destroy peace and create injustice. Sometimes it doesn’t even need to be fired. A police officer defending innocents is good. A murderous gunman surrounded by schizophrenic rantings is bad — and deserves the attention of parents and authorities.

No Discretion Allowed

To determine what kind of drawing they’re looking at, teachers could simply use discretion. Yet, unfortunately, discretion is what today’s inflexible school policies — and our increasingly litigious society — prevent. Every incident is treated the same, with no regard for the damage it may do to the child.

What is that damage? When a boy gets punished for drawing a weapon, he is being gaslit and emasculated. He will probably still be interested in guns, only now he’ll feel guilty for it. He’ll see his interest as psychotic. He may even be introduced — by his teachers — to the very adult concept of suicide.

As Michel de Montaigne, the great French Renaissance philosopher who believed in the philosophical, nonviolent education of children observed: “By punishing boys for depravity before they are depraved, you make them so.”

Whether we like it or not, guns and weapons are a masculine interest. And if you suppress healthy masculine interests, you tend to get a rebound effect, and not a good one. The only masculinity that is “toxic” is the kind that erupts when boys have no healthy outlets for these interests. Case in point: America’s schools keep suppressing masculinity and yet we keep getting more of what we don’t want — violence and fury.

The group of boys in Florida who savagely beat a 9-year-old girl on the school bus in an assault straight out of “Lord of the Flies” weren’t allowed to draw guns in school either. But they no doubt never learned what a fair fight is, or (thanks to our society’s obsession with erasing male-female differences) that there is a weaker sex. Did they have nonviolent guidance and love from adults, and a way — other than perhaps violent video games — to diffuse masculine interests?

In my interactions with teachers over this issue, I’ve been told time and again that they agree with me (or at least understand my points) but that “these are simply the times we live in.”

How Can a Child Understand?

This defeatist explanation seems to suit us adults for the moment, but does it make sense to a child? A 10-year-old doesn’t have the knowledge or the maturity to wrap his head around the “epidemic of school and mass shootings.” The rule only makes sense to him if we burden him with a dark, pessimistic view of the world — leading only to more anxiety and more shame.

He doesn’t know why his desire to draw a cowboy or an alien or a cop with a gun is a red flag. He just knows that Doc Holliday looks cool when he twirls his gun in “Tombstone.” He’s drawing the same doodle that a member of the Greatest Generation would have done in school, only he’s getting punished for it.

We should ask ourselves if the remedies that schools are employing to stop school shooters are only making normal little boys feel like psychopaths until they surrender to a softer, weaker, more effeminate version of how God created them. And then as parents who love our little boys, we need to do something about it.

Charlotte Schuyler is a mother of three boys, a freelance writer, a 2020 Claremont Speechwriters Fellow, and the director of member communications for the Conservative Partnership Institute in Washington, D.C.

Comments are closed.