Kidney Transplant Controller Wants To Distribute Human Organs Based On ‘Equity’

If someone donates one of their kidneys and later needs a new one, should they go to the top of the transplant waitlist? Yes, say good people. Yes, say normal people. Not anymore, say the bureaucrats in charge of the transplant waitlist. Instead, they say it’s time for a “more equitable approach.”

Currently, the people at the top of the kidney transplant waitlist are people who have donated one of their organs to someone else (living donors), young children who are a great biological match with an organ, and patients who are very hard to be matched with any organ. The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) is a private non-profit that holds a contract with the federal government to run the transplant waitlist, and they want to change that. UNOS wants to remove these “hard boundaries” in favor of a new system that erodes the protections for living donors.

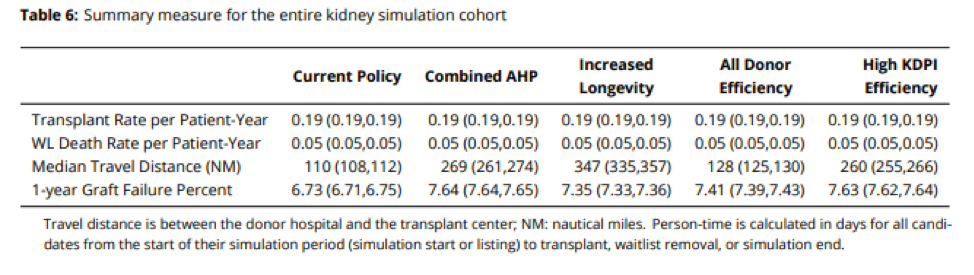

A report commissioned by UNOS envisions a drastic reduction in prioritization for living donors — going from the current virtual guarantee of getting a new kidney to a slight bonus on the waiting list — equivalent to as low as 10 percent of the total prioritization score. This policy would betray those who have already donated an organ and discourage others from donating in the future. They are pushing this policy even though their own research shows that changing from the current policy will not reduce death rates but lead to a higher rate of failed kidney transplants in the first year after surgery.

Why is UNOS doing this? They cite values such as transparency and equity. Often when people say a policy change is motivated by “equity,” everybody knows exactly what equity means. But for this policy, nobody knows what it means.

This new policy constantly refers to “improvements in equity,” but it’s not clear in what context. You might reasonably guess that this policy is meant to help black patients or other minorities, but the research commissioned to support this policy change shows that transplant rates by race and ethnicity will barely change.

Anything that discourages living kidney donation would be a disaster. Most transplanted organs come from people who agree to donate their organs when they die. You are probably aware of the option to volunteer to donate organs and many people check that option on their driver’s license.

Still, most of these would-be donors don’t actually donate their organs in death, often for logistical reasons. If you die in your sleep, your organs will not be usable when your family finds you in the morning.

That’s why living donors are so important and there are already far too few, especially living kidney donors. More than 90,000 Americans are hoping for a kidney transplant and so are more than 5,000 living kidney donors per year. Virtually everyone in the transplant world at least claims to support increasing living kidney donation, and some leaders have fought for that.

President Trump took steps to reimburse some living organ donors for part of the costs of living organ donation, as did Congress in 2004. But the very group in charge of the waitlist for deceased organs is now working to undermine living organ donation.

While the injustice to living donors is the most obviously wrong part of this proposal, the greatest harm will likely be to people who now don’t get new kidneys because living donation is discouraged. Kidney donors are screened for good health, and very few kidney donors ever actually need a kidney transplant of their own. This makes prioritizing living donors the obviously correct policy. It’s fair to living donors, it encourages living kidney donation, and causes very little competition for the pool of deceased donors with other patients.

When I donated my kidney in 2014, I was definitely reassured by the promise that if I needed a kidney, I wouldn’t have to wait long to get one. After speaking to many people considering donating their own kidney since then, I know how important and reassuring prioritizing living kidney donors is. Search for sites on organ donation and this reassuring promise is constantly repeated. Watering down protections for living donors will reduce living kidney donation.

Past changes to the kidney waiting list have discouraged living kidney donation before. In 2005, a new policy was implemented to move children who needed a kidney up the waitlist. Children got kidneys faster, but the number of living donors donating their kidneys to children fell.

Previously, parents or other relatives might have felt pressured to give their kidney to a young relative. Once they were near-guaranteed a deceased kidney, there was less need to donate. This policy helped kids get kidneys, but increased competition for the pool of kidneys coming from deceased donors.

Reasonable people are likely divided on the question of whether getting sick kids organs faster is worth having fewer living organ donors and a longer waitlist. But on this new proposal, the system would simultaneously be less just to future living organ donors and less effective, by discouraging future living organ donation.

After an online backlash to the proposal, UNOS has backtracked only partially. A spokesperson for UNOS, Anne Pashcke, claimed there had never been any intention for those who had already donated an organ to lose their priority, instead they only intended to minimize the priority for future living donors.

Pashcke added that though “a graphic on our website shows an example of how candidates may be prioritized under the continuous distribution framework, we want to clarify that the scores are placeholders and do not reflect the final points assigned to a patient’s score.”

This is hard to believe. First, the proposal produced by UNOS never mentions this distinction. They literally describe being a prior living donor as a binary condition: you donated or you didn’t. There is no mention of a distinction between those who donated before and after the rule change.

The policy proposal also cites a paper that attempts to estimate the effect of the proposed policy effect which also makes no distinction between past and future donors and envisions that at best 15 percent of the score that would now determine kidney allocation be based upon being a prior living donor.

Most people in the transplant field — surgeons, nurses, donors — are there to save lives. It’s time for UNOS to share that priority. Invocations of “equity” must never be an excuse to abandon living donors or discourage life-saving organ donations.

Comments are closed.