Goats First, Women Last–Air Force Culture Protects Perpetrators, Silences Survivors

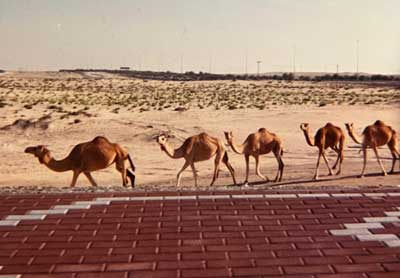

The city swirled around me in a kaleidoscope of colors: high-rises that gleamed in the sun like pastel-colored mirrors, palm trees with dancing emerald leaves, women in beautiful sparkly heels that peeked out from beneath their burqas. A line of camels walked along the road, pressed on by men in flowing robes. And in the SUV next to me, a goat sat in the front seat.

Wait, what?

I swiveled to verify what I saw and locked eyes with the animal. A woman in a burqa—perhaps the driver’s wife—sat in the back seat behind the goat. While my companions and I chuckled at the sight, I thought about how lucky I was to serve in the U.S. Air Force where everyone is equal, and where I had the opportunity to lead airmen supporting a combat mission. That mission was everything to me, and I felt prepared to do whatever was necessary to make it happen.

In a country where women were often relegated to the backseat—figuratively and literally—Stefanie Cooper felt grateful to be part of the U.S. Air Force, where everyone was equal. Or so she thought. Photo courtesy of the author.

Even more exciting: I had deployed as the logistics flight commander, responsible for aircraft maintenance, transportation, supply, traffic management, and fuels, unusual for a second lieutenant. I loved learning the different areas of logistics and took my role very seriously, spending time in each area and trying to learn as much as possible about all of my sections. My true love, though, was the flight line—watching airplanes repaired, prepped, and launched by my team fly away on refueling missions.

Briefings filled my first days on deployment. Some were more interesting than others, like learning about giant spiders, 10 types of venomous snakes, and 14 known species of scorpions in the area, complete with visual aids—specimens in formaldehyde. We also received briefings on cultural differences and how to interact with local nationals: Don’t cross your legs and show the soles of your feet. Off base, females should keep their arms and legs covered and be accompanied by at least two men. Don’t use the phrase “I don’t know, but I’ll find out,” or you’ll lose all influence. And, finally, it is the height of rudeness to refuse gifts of any kind.

I attended all the briefings and still completed a full day’s work. Before long, though, the jet lag, long work hours, and heat got to me. A constant headache, nausea, and dizziness plagued me for the first few days. An Air Force civilian permanently assigned to the area of responsibility noticed I wasn’t feeling well. He had grown up in the Middle East, so he recognized the signs of heat exhaustion. He offered me crackers and tea and chatted while I cooled down and my stomach settled.

A few days later, he showed up in the flight line maintenance area with a Dunkin Donuts coffee mug for me. Then he began stopping by my dinner table to check on me or bring cold bottles of water to my office. Usually, I checked on everyone else, so it was a nice change.

One day, he offered to take a few of the company grade officers off base to show us around. Since women weren’t allowed off base without at least two men, it seemed like a great idea to tag along. We went to the Souk, the marketplace where you could find almost anything—perfume, electronics, jewelry, carpets, spices, and more. The Souk also had beautiful 18-carat gold, and I lingered over a beautiful Byzantine chain bracelet I couldn’t afford before moving on.

A few days later, I found a jewelry box on my bed. Inside was the bracelet. Even without a note, I knew who it was from. I also knew there might be a cultural “issue” if I refused the gift. But I had to try.

The man was angry and offended that I did not want his gift and refused to return it. I discussed my concerns with senior officers about the increasing value of his gifts and was told refusing them wasn’t worth creating an incident—that I should be flattered and just accept them.

Stefanie Cooper on deployment. Photo courtesy of the author.

He continued to bring or leave me little things, or to come by the maintenance area to “check” on me. My maintainers thought it was funny, and it became a running joke to tease me about how often he stopped by.

When I asked him not to come to my work area, he told me his job cleared him to go anywhere he wanted. I told the senior officers that his visits were starting to affect good order and discipline and my ability to do my job. They blew off my concerns, calling him a “big teddy bear” and saying it was “cute” that he picked me for this rotation.

I knew I was good at my job, but at times I felt out of my depth, and the distraction and discomfort created by the unwanted attention made it that much harder. I didn’t have friends I could talk to, nor did I want to give the impression I wasn’t as ready or confident as the male CGOs. I also couldn’t leave my problems at work. I was deployed. I lived at work.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

Early on, I moved to a secluded female noncommissioned officer tent after the only other female officer on base—a KC-10 pilot with whom I’d shared a trailer—complained that my “crazy work hours” broke her crew rest. Sometimes two or three senior noncommissioned officers shared the tent with me, but mostly I was alone or with just one other person. Having space was a good thing in theory, but not when someone regularly enters your living quarters when you’re not there and leaves things on your bed. I couldn’t ask my roommates about it—they were on different shifts and most didn’t talk to me anyway, because I was an officer invading their space.

Besides the ad hoc female living arrangements, the placement of the women’s shower trailer required passing a very public area on base. I felt vulnerable walking by in my physical training clothes holding shower gear, or with wet hair and a towel. It was like I had a neon sign over my head proclaiming “she just got out of the shower.”

I showered quickly and tried to time my walk back to the tent to avoid crowds. Still, it seemed he was there more often than not, watching. When he talked to me, I’d try to cut him off so I could get back without him following me the whole way. As the days went by, my maintainers found it more and more entertaining that wherever I was, so was he.

I was trying to prove myself, but they saw me as the humorous object of a schoolboy crush rather than their maintenance officer. If we’d been friends, or if the teasing was about an actual, consensual relationship, I might have taken it as good-natured ribbing. But when the same people who won’t join you at an empty chow hall table think it’s OK to laugh and make fun of you, the balance of power has shifted and you start to lose respect even for yourself.

Eventually, one of the junior firemen noticed what was going on—and took it seriously. He came into the maintenance trailer and asked me if everything was OK. After a while, frustrated that leadership hadn’t intervened, the fireman went to the first sergeant. I don’t know what he said, but I was quickly called into the commander’s office.

Stefanie Cooper felt eager to prove herself as the logistics flight commander during a deployment, an unusual position for a young officer. Photo courtesy of the author.

When I reported in, I had to walk past the guy as he lounged in the reception area. Then the commander told me how important and critical he was to the wing’s mission, that “we sometimes misunderstand” people from different cultures, or take things the wrong way. Five minutes later, I left the commander’s office and watched the guy saunter into the office for a post-game recap.

That evening, I was excited to be invited to the “senior leader” fire pit—they had recognized me as part of the leadership team, I thought. My excitement turned to embarrassment as the talk turned to my “situation,” and I was given the choice to drop the matter or go home early. The guy had an important position on base and was irreplaceable, whereas lieutenants could be replaced as quickly as the next rotator. I didn’t want to be seen as running away or shirking my duty. I didn’t want that mark on my record, either. Besides, if my team stayed, I stayed. For the first time, I felt like I was really part of maintenance. I loved that the planes we launched helped make the Air Force’s combat mission possible.

I also didn’t feel like “just a cog.” By all reports, I was doing a darn good job, and I didn’t think I could be replaced as easily as they implied. I believed the choice they gave me—to stay or go—was less about what was happening to me and more about whether I was willing to “do anything” for the mission. I also understood that once I agreed to stay, the stalking issue was closed, not to be mentioned again.

Stefanie Cooper’s true love was the flight line, where she watched airplanes repaired, prepped, and launched by her team fly away on refueling missions. Photo courtesy of the author.

But the guy, and the problem, didn’t go away. After going off station for a few days, he suddenly loomed in front of me, blocking my path in the picnic area as I came out of the shower. I had gotten careless in his absence. I’d also forgotten how big he was until he was in my face. He was angry that the fireman had gone to the first sergeant and that I’d complained about him. When I tried to move away, he grabbed my arm and held me there. I feared what he’d do if I made a scene, so I looked around, hoping someone would do or say something. Most of the people at the picnic tables avoided looking at us; some gave us a half-embarrassed, half-interested side-eye. When he finally let go, I started edging toward my tent. He followed, taking a possessive tone.

Did I look like I was OK? Did people think it was a quarrel they shouldn’t get involved in? I hated not having the armor of my uniform on. And I hated feeling weak. By now, I knew no one would help me, even if I asked. When I said I wanted to remain on deployment, it became my battle to fight alone. For the remainder of my time, I got on with the mission—I worked crazy hours to prove I belonged while constantly looking over my shoulder and trying not to do anything that might provoke him.

Several months after I returned home, I got an email from an airman at the deployed location. She was the new “chosen one,” and she’d heard through the grapevine that I had been his last.

My heart leaped into my throat. If the people in the grapevine knew what happened to me, where had they been when I needed them? Then: If I hadn’t kept my head down, if I’d decided to pursue the wrongdoer, then this airman wouldn’t be going through the same ordeal.

For months I’d questioned myself and replayed my words and actions, wondering if I’d been wrong. Now I knew what had happened to me was real. I did my best to encourage her and talk through the options of what to do next. Shortly after, I got a call from an investigator whose questions implied that I had led the guy on by accepting his gifts, or that I’d misunderstood his actions, or that I had just taken things the wrong way. I felt as if I had to prove my innocence. But if everyone knew he had a pattern of picking one woman per deployment rotation, how could that be on me—and the other women? How could so many women “misunderstand” the same man?

Pride quickly turned to embarrassment, fear, and anger when Stefanie Cooper became the victim of a stalker during her deployment. Photo courtesy of the author.

I got another surprise when the guy himself called me at work, invading the safety of my home station. He implied that certain things could happen if I talked to investigators and that things could look bad for me. I told him he was too late, I had already talked to them. After that, I never heard from him or the investigators again. I never heard from the airman again, either.

What happened to me was years ago. Yet the Air Force is still trying to figure out how to ensure victims of sexual assault and harassment get the support they need and deserve. Fifty-four percent of airmen who took a 2020 Air Force survey on interpersonal violence (IPV) said they’d experienced behaviors consistent with IPV, including sexual assault, dating violence, and workplace violence—harassment, hazing, and bullying—in the last two years. Following the report’s release, the Air Force chose seven bases to launch the Integrated Response Co-Location Pilot Program, a fancy name for having all the support a victim needs in one place. Even after all this time, the Air Force’s focus is still on the victim, the aftermath of the crime, and not on changing a culture that allows these things to happen in the first place.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

When I was a lieutenant, if you weren’t physically or visibly hurt, most people didn’t want to hear about it. You did your job and either you or the perpetrator eventually moved on. Once I was back home, I did my best to forget about what happened to me. I didn’t talk about it.

Not only did I have to deal with the trauma of a stalker on my own—yes, a stalker—my leaders showed they didn’t care about me, or the impact it had on my job. They could not be trusted. If only leaders believed everyone in their organizations had the right to a safe work and living environment. The right to be seen as a peer rather than a distraction. The right to be heard.

I sometimes think about that goat in the front seat and my naive belief that I had it so much better than the woman relegated to the back. My deployment showed me that inequality still exists in the military I was willing to sacrifice everything for. Until the Air Force starts focusing not just on support for victims but accountability for the perpetrator and those who allow them to go unchecked, we will always be the woman behind the goat.

Comments are closed.