China Has a Youth Unemployment Problem; Guangdong Province Spearheads a Plan to Send 300,000 Youth to the Countryside by the End of 2025

China Has a Youth Unemployment Problem; Guangdong Province Spearheads a Plan to Send 300,000 Youth to the Countryside by the End of 2025

China Change, April 7, 2023

Since the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS) started to publish the country’s monthly unemployment rate in January 2018, the unemployment rate for young urban workers aged 16-24 (including migrant workers living in urban areas) over the past five years has increased from 11% in January 2018 to 19.9% in July 2022, then decreased slightly to 18.1% in February 2023.

Combining the myriad unemployment stories posted on social media, anecdotes from college campuses, with our justified distrust of Chinese government statistics, we believe that the youth unemployment rate is far higher.

This labor force is composed of recent graduates from junior high schools, high schools, vocational schools, undergraduate studies, and master’s degree programs, including returning international students to China. According to the World Bank’s China Economic Update, Special Report on Youth Unemployment (December 2022), about 39.8 million vocational, undergraduate, and graduate students have entered the labor market in the three-year period from 2020 to 2022, and about 11.5 million more will enter the labor market in June 2023. This does not include graduates from conventional middle and high schools entering the job market.

If the job market in China does not turn around quickly in the near future, there will be at least a few millions of young people between the ages of 16 and 24 — including the well-educated — unable to find employment. Tellingly, the phrase “out of school equals out of work” (毕业即失业) has been making headlines in Chinese media and social media in recent months.

The internet, education, manufacturing, service and entertainment industries, where young people are concentrated, have been hit hard in recent years, with severe layoffs and declining revenues, and job prospects for young people in the foreseeable future are not looking up. For those who do find jobs, job instability may be high.

From a statistical perspective, youth unemployment does not seem to be much of a concern. Based on the China Census Yearbook 2020, a macroeconomic research report by Orient Securities states that the share of employed people aged 16-24 in the employed population decreased from 14.3% in 2010 to 7.1% in 2020, due to changes in population age structure; the shift in the overall unemployment rate is only 0.07% for each 1% increase in the youth unemployment rate.

However, high unemployment among the youth could be of grave political concern for the Communist Party.

Compared with previous generations of Chinese, those born after 1990 belong to the most fortunate generation in recent history: they have a better standard of living than ever before, their families have been willing to invest in them, they have grown up with more freedoms and more education, and they generally are full of optimism for the future. Many of them have studied abroad; the cultural trends they follow are heavily influenced by the West, especially the United States. Now, just as their lives seem ready to take off, the course of history may have turned: the good life they are used to may not be getting better; the period they have grown up in may well be a fleeting aberration rather than a sustainable norm.

Unlike the 1989 generation, today’s youth have not grown up with a keen interest in politics. But last November, they were the ones who took to the streets across major cities to protest the cruel and foolish zero-Covid policy. We do not know the deliberations within the CCP, but following the Blank Paper protests, the CCP may begin to see young people, besieged by unemployment, as a potent destabilizing force and take more forceful measures in response to this problem. It is perfectly in line with the CCP’s logic of nipping potential threats in the bud and maintaining regime security at all costs.

The new “send-down” plan

On February 20, the Guangdong Provincial Committee of the Communist Youth League held a “mobilization conference for Guangdong youth to aid in high-quality development” and officially announced a plan to send 300,000 youth to the countryside by the end of 2025, with the tongue-twisting title “The three-year action plan of Guangdong youth going to the countryside, returning to the countryside, and rejuvenating the countryside to help the project of high-quality development of 100 counties, 1,000 townships, and 10,000 villages.” There was a lot of news coverage of this mobilization conference, but it wasn’t until a few days ago, when someone revealed the full text of the plan on Twitter.

The plan consists of three parts: organizing city youth to go to the countryside; mobilizing rural youth living in the city to return to the countryside; and cultivating youth in the countryside to make them stay in the countryside.

The plan to “organize city youth to go the countryside” has three components:

1) Each year, 10,000 graduates from colleges in Guangdong are to be sent to less developed parts of the province for two to three years of “voluntary services” to provide talents to “rural rejuvenation.” According to the plan, the young volunteers will assume the positions of Communist Youth League cadres, promoters of rural rejuvenation, and liaisons for young people returning home, and service personnel for formerly rural townships recently redesignated as urban areas. And favorable policies will follow to “encourage and support volunteers to put their roots down.”

2) Each year, 1,000 teams of volunteers, consisting of vocational school students, are to go to the countryside during the summer to provide technology know-how to rural enterprises, startups, and government’s key projects and help train locals.

2) Each year, 1,000 young entrepreneurs from inside and outside the province are to be recruited to participate in the development of townships and villages.

The plan to “mobilize rural youth living in the city to return to the countryside”: Each year, a minimum of 30,000 college graduates will be sent back to where their rural household registrations are. Municipalities and counties will have a system to register local youth who have left for colleges and provide them with internship or job opportunities to incentivize them to return home.

The plan calls for “helping train 30,000 rural-based youth” each year to engage in digital commerce, farming, and cooperatives (合作社), which was a relic of the Mao-era planned economy and is seeing a government-led comeback in rural China. The government will support 3,000 such startup projects each year by providing loans to recent college graduates returning home.

Chinese netizens and commentators immediately dubbed this plan “the new educated urban youth being sent down to the countryside” (新知识青年上山下乡).

Will it work?

When Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution in 1966, he mobilized college, middle and high school students to be the vanguard revolutionaries known as the “Red Guards” to destroy the country’s bureaucratic system, or the “capitalist-roaders,” as well as the “five black categories.” Schools closed and colleges ceased to admit students. By 1967, violent fighting broke out among factions of Red Guards. By the fall of 1968, Mao wanted to resume some degree of normalcy and rein in the political fanaticism, but the economy had been wrecked and there were no jobs for young people. In December 1968, Mao ordered urban students who had graduated from secondary schools in 1966, 1967, and 1968 to be “sent up to the mountains and down to the countryside” (上山下乡). Millions of youth from large urban centers such as Shanghai and Beijing were sent to China’s remote provinces and backwater regions. In the years that followed, the “send-down” policy was expanded nationwide and wasn’t terminated until 1978.

There are similar forces motivating the old send-down and the new send-down: with urban job opportunities drying up, restless youth could be a source of trouble for the regime. But today, the countryside is no longer collectivized, and there are no wholesale ways to plant large numbers of youth in rural communities and keep them there.

To be sure, there have been countless remarkable young farmers and agricultural entrepreneurs. And in recent years China has been encouraging young people to go (or return) to the countryside. The state media are filled with success stories of young people going into agriculture or starting business in the countryside, some bordering on cheap, cringeworthy romanticism.

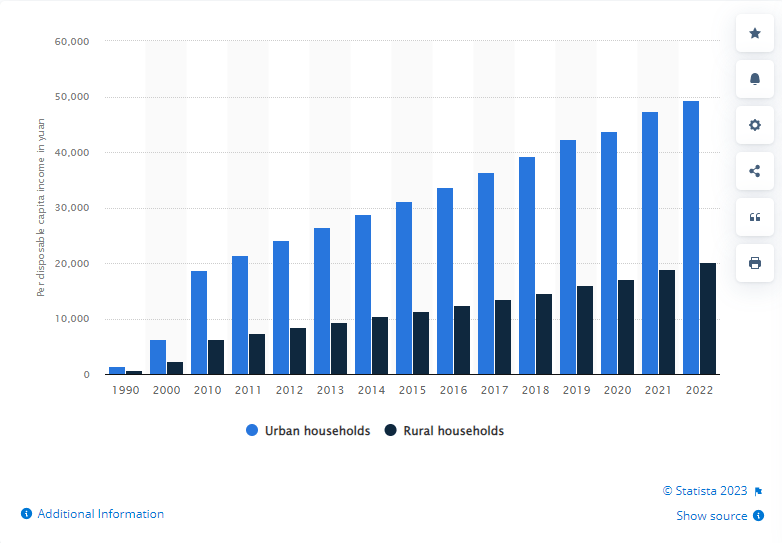

Contrary to the image popularized by the state media and influencers such as Li Ziqi (李子柒), the Chinese countryside is no idyllic paradise. On the contrary, China’s two-tier urban vs. rural household registration system has long functioned as a veritable caste structure that treats more than half of the population as second-class citizens with little access to health and social benefits; until roughly three decades ago, rural Chinese wholly lacked the freedom to seek jobs or live in cities. During the 40 years of reform and opening up, rural labor has built roads, bridges and buildings, and manned factories humming all over China. Yet according to former premier Li Keqiang, there are still 600 million Chinese whose monthly income is below 1,000 yuan (about USD$150). For rural parents, the most important achievement of sending their children to college is that their offspring will forever be freed from the curse of being in the countryside. Young rural Chinese, especially those with college degrees, also find themselves under considerable pressure to make it in the cities, rather than become a “disgrace” to their families.

Last April, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs said over 11 million people (no time frame given) have either gone, or returned, to the countryside to start businesses. But Kong Dongmei (孔冬梅), chair of Dongrun Foundation (东润基金会) and the granddaughter of Mao Zedong, said recently that most of these people quickly gave gave up and returned to the cities.

A 2018 survey of 1,231 young people who returned to the countryside in H province and Z municipality in central China to participate in “rural rejuvenation” commonly encountered the following difficulties: in the countryside, conditions are not conducive to starting businesses, government policy support is lacking, opportunities for their children to receive quality education are rare, health care is poor, wages are low, and there is a short supply of skilled people.

In addition, it must be noted that rule of law in the countryside tends to be even weaker and corruption more severe than in the cities. Villages are often run by families with strong connections to government officials; business is conducted at the mercy of layers upon layers of local regulators and their illicit interests. Even Sun Dawu (孙大午), the agricultural entrepreneur famed for his multi-billion yuan success, couldn’t escape the fate of being sentenced to 18 years in prison on trumped-up charges and his conglomerate being sold to a company registered three days before Dawu Group was auctioned off in April 2022. There are many Sun Dawus, big and small, throughout China.

“For this kind of policy to be effective, they have to fit young people’s own career planning and what they want for themselves,” said Lu Feng (卢锋), a professor at Peking University’s National School of Development. “Only then will young people consider long-term careers in the countryside and contribute to rural development.”

The scope and vision of Guangdong’s action plan seems unlike the constant cajoling by the government, media, and schools seen in previous years, but the question, as always, lies in its implementation. China’s economy is slowing down and jobs are becoming more scarce, for not just young people, but across all cohorts of the labor force. Given the proclivities of Communist Party politics, Guangdong, though having long been a magnet for young people attracted to its strength in manufacturing and foreign trade, could well end up spearheading a modern repeat of Mao’s coercive population transfer.

Recent posts:

Taiwan Interview Series (2): Lin Ping-yu, Member of New Taipei City Council, March 30, 2023.

A Protest Song Has Emerged in China — It’s the Communist Anthem, Yaxue Cao, March 5, 2023.

Comments are closed.