‘Gender-Fluid’ Is The Poisonous Fruit Of The ‘Keep Your Options Open’ Gospel

Netflix subscriptions. Marriage. Terms of service agreements. Text messages. Social media posts. Pregnancy. Amazon purchases. Aging.

According to our consumerist social catechism, each of these actions is reversible. Click “cancel.” Get a divorce. Dig through your privacy settings and revoke permissions (even though you know you’re never going to). Unsend. Delete. Get an abortion. Return for free with a preprinted label. Get plastic surgery.

For young people raised in this “Ctrl-Z” world, unfamiliarity with the irreversible breeds suspicion, which translates to avoiding commitments. It’s no surprise few of my generational peers are getting married and having kids — although the culture tells us those commitments are still changeable, they’re actually messy to get out of and necessarily close other doors.

We are taught to believe limitations are inherently oppressive and therefore bad. Keeping your options open, on the other hand, is liberating and therefore desirable.

Some limitations, like those of becoming a parent, we choose to enter into and therefore can choose to avoid — which young people increasingly do. Other limitations are innate and unalterable. But to the restriction-averse, that inescapable nature makes those even more threatening. One of those fearsomely unchangeable limits is our biology: We are afraid to be limited by our natural sex.

Here’s how Amelia Blackney, a 13-year-old girl who decided to start going by the plural pronouns “they/them” and identifying as “non-binary,” explained her decision to CNN:

That way it’s like I’m not a part of any gender or I can be both genders at the same time. My pronouns now put me at a place where I can decide between different genders. That feels right.

If limitations are to be avoided — or overthrown — why would you tie yourself down to being either a girl or a boy? Why limit your prospects to growing up to be either a man or a woman? If you could be gender-fluid, all doors remain open to you. You don’t have to choose to be a she or a he, you can be they! Your options become unlimited. Subscription to being a woman, canceled.

Another child, 14-year-old Sylvia Chesak, described how she was “uncomfortable” thinking of herself as “just” a “she,” and chose to use “any pronouns” as a result.

These children, or the adults who egg them on, revolt against the sex they say was “assigned” in infancy. The nonsense language of “assigned at birth” doesn’t only make the wrong assumption that sex is nonexistent until it’s decreed by a doctor. It also makes the subtle implication that by doing the “assigning,” a doctor is imposing a category — a limit — on an infant that is inherently restrictive and must be abolished. Physical limitations like a man’s inability to get pregnant don’t matter, just like the physical limitations of a kid with Coke-bottle glasses who wants to become a pilot don’t matter to the adults telling him he can “be whatever he wants to be.”

One mother wrote in Time magazine about choosing not to call her child, named Zoomer, either a boy or a girl because she didn’t want to impose the “chains” and “restrictions of the gender binary.” Even after her child expressed a desire to be treated as a particular sex, the woman insisted on calling her child “they” in the article.

Elsewhere, she says, “The aim isn’t to create a genderless world; it’s to contribute to a genderfull one.” In other words, rejecting the sex binary isn’t about erasing sexuality, but removing all of its categorical limits.

A Swedish mother similarly explained that she refused to acknowledge her child’s sex “just as I don’t want to decide what they grow up to do…”

Telling children they can be and do “anything” helped create a generation petrified of narrowing their own options. They date around indefinitely to keep options open in case something better comes along. In the same way, kids learn to keep open the “option” of being a boy or a girl or a xe. Your natural sex is bad because it limits your possibilities.

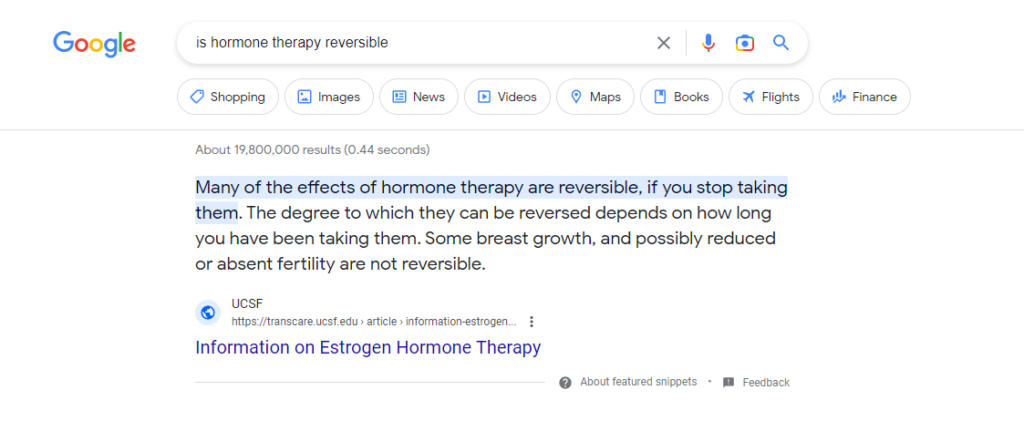

Of course, your possibilities become far more limited when a doctor chops off your breasts or genitals or pumps you with hormones that may permanently alter your voice and body and keep you from ever having children. But just examine the messaging those hormones are marketed by: They’re reversible. You can just stop taking them. Here’s what Google would tell a curious teen, though the fine print is far more complicated than the highlighted answer suggests:

The messaging for puberty blockers is even more overt. Delay puberty, St. Louis Children’s Hospital tells kids, if you want “more time to explore [your] options.” What teen wouldn’t want that?

The reality is, of course, that some limits are outside our control. As for the limits we choose by the commitments we make, it’s far more paralyzing to artificially keep every option open than to choose wisely and live within the natural limitations of an ordered life. For kids getting transed into oblivion, that paralysis may be literal. But for all of us, refusing to commit to decisions worthy of our commitment will leave us lonely, exhausted, and bitter. Eventually, people who don’t want to limit their “options” by getting married usually realize one day that they don’t like any of the options left. Those who never put down roots typically end up adrift.

Thankfully, accepting our finitude is liberating. By recognizing the divine order that confines us, we are freed from struggling against it, and freed to do well in the things that are within our power.

In that latter realm, we have the gift of making choices and commitments, not so that we will avoid ever making them, but so that we may choose what is good. From choosing to work hard, to be loyal friends, to profess our faith, to raise children, to be faithful to our spouses, good choices place obligations on us, many of which are permanent. The fulfillment of those obligations enriches our lives, offering a depth of meaning and satisfaction that “keeping our options open” can never provide.

Elle Purnell is an assistant editor at The Federalist, and received her B.A. in government from Patrick Henry College with a minor in journalism. Follow her work on Twitter @_etreynolds.

Comments are closed.