‘Lead, Follow, or Get out of the Way’–We Really Did Live That Way.

IMPACT minus 2 hours and 1 minute

You could always identify the schedulers. They were the ones who ran from room to room attempting to fill flight sorties when instructor pilots had canceled for some reason or another. That morning was no different.

“Hey, Dan,” Tom said with a mix of hope and pleading in his voice, standing square in front of my desk waving a binder to emphasize the importance of the moment. “Could you help me fill a four-ship? The brief is in 27 minutes. My guest help just dropped.”

I looked up from my desk where I was completing paperwork from a student check ride.

A T-38 Talon four-ship formation flies over the Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup on July 27, 2022, in Sacramento, California. “It was a great jet nicknamed ‘The White Rocket.’ … But it was also unforgiving and unpredictable with the unprepared at the controls,” writes Dan Woodward. Photo by Senior Airman Frederick A. Brown, courtesy of the U.S. Air Force.

I liked Tom. Like almost everybody in the squadron, he was about 25 years old, lean, and newly married, with a lifetime of great dreams ahead of him. His hair was dark brown, accentuating dark brown eyes, an ever-present five o’clock shadow, and smooth olive skin.

Figuratively, we were brothers. Both Air Force instructor pilots flying advanced T-38 trainers. It was a great jet nicknamed “The White Rocket.” Very fast and able to bend a pretty sharp turn in blower, a term we used for the afterburners which added a real kick of thrust. But it was also unforgiving and unpredictable with the unprepared at the controls.

Tom flashed me a used-car salesman grin. I gave him a look that said “knock it off” and his smile grew quickly even.

“What the hell, Tom?” I asked. “Twenty-seven minutes to a four-ship brief?”

“I know,” he said, “but Maj. Ski just dropped. I gotta fill this sortie. Strong student.”

Ski had a reputation for doing this.

I knew the drill. I had been a scheduler as well, and this was my job and Tom knew it. I had the white space on my schedule, and he knew that, too.

“OK, Tom, OK. I’ll fill the seat. But, do me a favor, ask Tony, too. He’s a stick hog, and I really want to catch a workout over lunch.”

Tony sat next to me in this office. He really was a stick hog, meaning he would grab a flight every chance he got. He was also a good friend and a pilot training classmate of mine. We received our wings the same day.

Six-foot-two and around 200 pounds, he was a gregarious guy that you always felt was just a step away from giving you a bear hug that would crush you like a grape. Like Tom, Tony was my brother.

Tony was also finishing paperwork from a check ride, so Tom dutifully stepped to his desk and unloaded the same pleading request to Tony, adding something about me taking the sortie, if he could not. As expected, Tony the stick hog took the sortie, and Tom headed out the door after tapping my desk and saying he had it covered.

“Great,” I said.

It was the last time I would see Tom.

Twenty minutes later, Tony walked by my desk. He looked like he was on his way to bench press a refrigerator. That’s how he always looked to me. It was the last time I would see Tony, too.

IMPACT minus one hour and 38 minutes

Additional paperwork complete, I popped up from my desk, grabbed my workout bag and headed through the length of the squadron. It smelled a little like a locker room and looked like a beehive, as students and instructors hurried in and out of flight rooms and the life support area where parachutes, helmets, masks, and G-suits—designed to keep you conscious when G-forces pushed the blood to your feet—were stored. The operations desk and flying supervisor had the usual 10 or so people ready to go, and a solid hundred sorties for the day were posted across a monstrous scheduling board in four-minute increments.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

I walked past J Flight where Tom and Tony were briefing the four-ship. I didn’t give it a thought. I put one foot in front of the other.

I popped out the squadron door and headed for my car, walking past Tony’s giant, ancient Cadillac or Chrysler or whatever it was. All I knew was that it was old and enormous and sounded like an old man with bad knees when Tony fired it up. I hopped in my car and headed for the gym.

IMPACT minus 58 minutes

“Heat check,” the student blurted into his mask-integrated microphone.

“Two, three, four,” came the response, indicating the formation was ready to taxi. You did not screw this part up. You sounded good and you looked good when you taxied in front of God and country and, most importantly, the other guys in your squadron. If you didn’t, everyone would shit on you.

“Heat 21 flight, cleared to taxi to runway 31 center, wind 330 at 10, altimeter 29.98,” ground control transmitted.

“Heat 21, 29.98,” came the student’s response.

About this time, I headed out of the gym after changing and started my usual run around the base. It would take around 40 minutes, then another 20 or so for a shower and quick slide back into my flight suit before heading to the squadron.

Everything was on track that day, until it was not.

“Why,” a statue dedicated in 1967 to service members, stands in front of the Placer County offices in Auburn, California, which Dan Woodward visits often. Photo courtesy of the author.

The formation executed an eight-second interval launch with lead accelerating to 300 knots, while the additional three jets accelerated to as much as 450 knots in blower to join the formation, with three-foot wingtip separation.

Another buddy of mine was lead for the moment, and he took the formation through the Pickwick departure corridor en route to the Pickwick military operating area. Leveling at 14,000 feet, the formation was cleared by Memphis Center for Pickwick high and low military operations, meaning the flight could use every foot from 8,000 to 23,000 feet.

They started to climb.

IMPACT minus 19 minutes

Anything still could have changed at this point, but it didn’t.

I headed out of the gym, freshly showered and getting mentally ready for my late afternoon check flight. I pulled into the squadron parking lot and hopped out of my car, walking past a giant mural painted on the squadron exterior that said simply, “Lead, Follow, or Get Out of the Way.” We really did live that way.

Through the squadron doors, I returned to the beehive, walking the length of the building to my desk. There, I pulled out a bagged lunch from my side drawer and swallowed a peanut butter and jelly sandwich by practically unhinging my lower jaw from my upper jaw like a snake. After all, why waste time eating when all that did was get in the way of the mission? Lead, Follow, or Get Out of the Way.

I glanced at Tony’s desk. His flight jacket was draped over his chair. Plexiglass covered his desk and protected a dozen or so dollar bills presented by students following their first flight, and another dozen or so patches from student classes he had flown with. The lights flickered as they did from time to time, and in that chair, for an instant my gregarious brother sat, and then he was gone.

IMPACT

Physics is a profoundly unforgiving mistress. For every action there is a reaction. Military aviation marries you to this reality and all others in the natural world. Tony knew this. We all did. But it didn’t make things easier when physics turned on you.

He pitched up and pulled right and then down to the buffet, where the jet told him he was demanding all it had. As number three in the four-ship, he was responsible for taking his aircraft and the number four aircraft back to the lead element, solving the complicated geometry of closing two jets on another two jets at 400 knots as they maneuvered 4,000 feet away.

This was a tactical rejoin, a basic building block in creating a combat aviator. Spread wide to facilitate clearing and radar coverage for enemy jets in the future, flight lead had decided to bring the formation back to three-foot wingtip separation to practice other skills.

Crossing behind lead at nearly 500 knots, Tony pitched to the outside of the turn, and, needing additional closure to expeditiously join, he reversed and pulled hard back to the inside.

His wingman, the number four aircraft in the formation, could not respond quickly enough and pulled to match Tony’s pull too late to clear the flight path. Both aircraft exploded on impact, with Tony’s jet smashing his wingman into unrecognizable debris behind the front cockpit. Tony, Tom, and Will, Tony’s student, touched the hand of God, and chaos brutally shoved itself into the lives of everyone they knew.

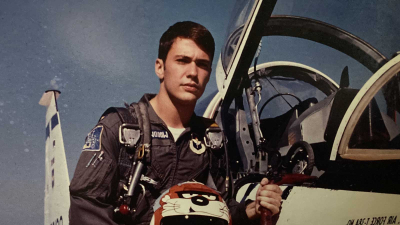

Dan Woodward pictured near the end of his pilot training. One of his classmates, Tony, would later die in a T-38 trainer crash. Photo courtesy of the author.

This story goes on, but last night I asked Tony to help me with clarity and brevity, so he took my pen. Did I mention he was a stick hog?

I sat at my desk and the lights flickered. I looked at my friend Dan. He had just eaten a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and was wondering what was going on as the squadron went into lockdown.

I would not be back, but I would always be around. Dan would always remember me, and Tom and Will too. He was our brother. I would never tell him that, but he knew it.

He would meet my mom, pack my clothes, meticulously build my service dress, pay my bills, place a new medal on my uniform, and drive my car home for the last time. I would not thank him, but he knew I would if I could.

Someday when the leaves were changing in his life, and the time was right with brothers and sisters he knew forever but met only briefly, a question long buried would come to the surface.

Why? Why them and not me? Why that day? Why that way?

Here is what I told him.

You were not to blame. You could not know what rested in the future, and in the future, you must not dwell on the pain of the past.

You can disrupt the ripples in a pond, but you cannot stop them. Be at peace with it. I am. I took the flight. You did not give it to me.

Your life gives value to mine. You lived on for a reason, and I want nothing more than to see that reason fulfilled.

When you walked by J Flight, you put one foot in front of the other. Keep doing that.

For every action there is a reaction. React toward the light and away from the dark. I do not need you closer to me. Not yet.

My friend, lift up those around you. Inspire them. Speak for me. Act for me. Laugh for me. But do not cry for me. There is no time for that, because you never know when you too will touch the hand of God.

I got up from my desk and walked over to Dan. He sat there still confused by the commotion of the moment unfolding around him. I gave him a hug and crushed him like a grape. I always wanted to do that. He would be fine.

The lights flickered, and I was gone. But always around.

Comments are closed.