It’s Every Young Marine’s Dream. But I Don’t Like This Story.

Marine Maj. Andrew Hesterman first saw combat up close as a grunt during the Gulf War. His career culminated as an officer in the Iraq War, where he directed air support for the Marines in Fallujah.

In this excerpt from Radioman: 25 Years in the Marine Corps, written by Hesterman and co-authored by Robert Einaudi, he relives a night shortly before the ground war in Kuwait that he has rarely spoken about.

I always took crap for wearing a KA-BAR knife inverted on the left front strap of my battle harness. I think most guys gave me shit because they were jealous they hadn’t done it first. I used several wraps of green riggers tape around the scabbard and always made sure the pommel strap was fastened so it didn’t fall out.

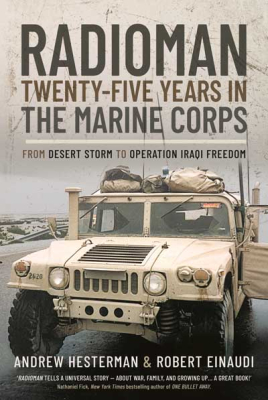

25 Years in the Marine Corps, by Andrew Hesterman and Robert Einaudi, was published in February 2022 by Pen & Sword Books.

25 Years in the Marine Corps, by Andrew Hesterman and Robert Einaudi, was published in February 2022 by Pen & Sword Books.

Wearing a KA-BAR on your battle harness has its roots in the serious fights of history when getting into a knife fight in combat was a real possibility. But with the weapons systems and sensors of the 1990s, getting into a knife fight was highly unlikely. It was kind of showy to wear my knife there, and I would admit that the most use my knife would ever get was opening an MRE bag. But a good knife is a valuable tool, and I wouldn’t dream of going to the field without it.

The next trip up to the berm started like all the others. “Thunderstruck” blared from the tiny speakers on the boom box while we unloaded, cleaned, and reloaded magazines, weapons, radios, night vision goggles, etc. Then we gathered around the captain on the ramp of the M113 just before sunset to get the final brief. We were headed to one of the police stations we’d been to previously. No one had been there in a couple of days. We would clear it as usual, except this time, I would get to lead the stack. I was amped.

The point man is usually the one who triggers the booby trap or the ambush, but it’s a Marine bravado thing to be the first one and I’d been looking forward to getting my chance. It meant I got to wear one of the two pairs of night vision goggles for the night. It also meant I didn’t have to hump a radio—the problem with being good with radios is that you always have to carry one.

The berm—the border between Saudi Arabia and Kuwait to the north—at the start of the U.S. ground assault in 1991. For many troops, it was their first look into Kuwait. In the background, a bulldozer waits to cut a gap for troops to drive through. Photo courtesy of the author.

The drive up went much the same and we parked the vehicles just inside a klick south of the police station. It was a little lighter that night—maybe because the overcast was thinner—and we could see the moon and some stars. We dismounted the vehicles and I double-checked my night vision googles adjustments. I could see the outline of the mini castle of the police station on the horizon. I stayed on one knee in front of the Humvee for a few minutes watching the police station for movement. Thompson was next to me, my battle buddy for this go-round. Howsen and Peterson were staying with the vehicles and the rest were fanned out to our sides. In a hushed tone, the captain said, “Whenever you are ready, Hesty.”

I stood up and started my patrol walk toward the station. I watched the building outline carefully as I approached, then scanned down at the blurry ground in front of me. I walked at a slow deliberate pace, placing my feet by starting with the outside of my heel, then rolling down the outside of my boot then across the balls of my feet. I scanned the building, looked where my next footstep would land, then made a quick glance left and right back to the next Marine. The entire time, I had the rifle pointed at the building. Ten meters to my left, Thompson was doing the same thing. His distance was perfect because that was right where things came into focus with my night vision goggles. When I scanned over his way, I could see his facial expressions.

It was slow going, but everything was nice and quiet, and after a few minutes we stacked up at the bottom of the berm. I looked left and right to make sure everyone was in position, then gave Thompson the exaggerated double nod. He followed me up the berm as soon as I started moving. The berm was only six or eight feet high, and the slope was fairly gentle. As soon as we cleared the edge, we covered the five meters to the south wall of the building, scanning the large window, then the roofline, the edges of the building, then back to the window.

Andrew Hesterman with his captured AK-47. Behind him is a ZPU-4 anti-aircraft gun they captured. It is now on display at Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego. Photo courtesy of the author.

The window was a black hole against the light-colored cinder blocks. It was about six feet wide and the bottom would be even with my gut if I were to stand straight up. There wasn’t anything in the window. I crouched on the ground two feet from the wall, at the right edge of the window with my rifle pointed up.

A double pat on my shoulder told me Captain and Shue were ready behind me. Thompson gave me a blurry left-handed thumbs-up. I did a quick leg extension to peek through the window then dropped back to my crouch. I paused just a second to let what I saw sink in. The doorway was opposite the window and was open and clear. There was the usual debris on the floor but it was out of focus. That’s about all I’d been able to take in.

I gave Thompson the double nod. He was on his left knee with his right foot on the ground giving me a step with his right knee. In one motion I stood up, put my left foot on Thompson’s knee and left hand on his helmet, sprung up, and swung my right leg up and into the window. I half-rolled my back and butt across the sill and swung my legs down beneath me as I dropped down to a crouch inside.

I had intended to bounce off the inside wall and immediately run to the left corner. But I miscalculated the distance to the wall, so when I leaned back to push off it, I rocked back on my heels and lost my center of gravity. I struggled to regain my balance when someone grabbed me from my right. A blurry hand was on my rifle and another hand gripped my right bicep. As I attempted to turn and face my threat, I slid down the wall and rolled onto my back. My attacker rolled on top of me and we wrestled with my rifle.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

I couldn’t see anything but flashes of green and dark green through my night vision goggles. I considered attempting a head butt but couldn’t because of the way I was pinned on the floor. I wanted to punch him but I didn’t want to let go of my weapon—a cardinal sin in the Marine Corps. We seemed to wrestle for an eternity, pushing and thrusting back and forth with my rifle. Then I realized my KA-BAR was just inches from my right hand.

Wild Eagle Two Five, just south of the Kuwaiti border, in January 1991. The team sat on the border almost every night calling airstrikes and artillery missions onto targets in Kuwait before the ground war started. A smoky haze fills the sky from Iraqi oil well fires. Photo courtesy of the author.

I released my grip on my rifle and in one motion pulled down on my knife and thrust immediately back up and out. I thrust where I imagined the bottom of the attacker’s rib cage would be. The resistance to my thrust gave way so quickly that at first I thought I had missed. But the guttural moan I both felt and heard and the warmth running down my hand and arm told me otherwise.

I was really pissed. Pissed and confused. I was supposed to be in the corner ready to fire on anyone coming through the door. Instead I was lying on my back, knees drawn up with someone on top of me, and I didn’t even have proper control of my rifle.

I was on my second or third shove and twist—not really drawing the knife out, just pushing in harder—when my attacker was lifted off me and disappeared like a rag doll through the window.

I scrambled to my feet and ran to the corner of the room. I sheathed the knife and got my right hand back on the pistol grip with my finger along the trigger well. A Marine dropped through the window and went to the right corner and then another came to my corner. I crossed to the next corner and slid along the wall to the door. I was at the edge of the door frame, just off the wall. I choked up on my rifle like a batter going to bunt to keep it pointed through the doorway but not protruding through the doorway.

The rushing in my ears started to fade and I could begin to hear again. I heard a “Go!” from behind me. I crossed through the door headed for the right-hand corner this time, clearing in front of me and to the left. We cleared the rest of the building without incident. No one else was there. We consolidated on the roof as usual, and the captain told me to keep watch from the roof while everyone else brought the vehicles up and got set up.

Andrew Hesterman with his good friend, Pat, at the airport after the end of the Gulf War, when Hesterman could finally relax a little. Photo courtesy of the author.

As I stood there peering into the green darkness, everything started to sink in. I felt like I was covered in blood and really wanted to turn on my flashlight to see. But tactically that was a really bad idea, so I just stood there staring out into the darkness, trying to shrink back from my clothing so the wetness wouldn’t touch me.

After they got all set up, the captain came back up to the roof and we sat down and talked for a bit. We didn’t really talk about what had just happened but I thought he was trying to determine if I knew how badly I had screwed up. I didn’t apologize exactly, but I tried to let him know that I would be where I was supposed to be at all times. He told me I had nothing to worry about, that everything was fine and I should go back down and get in the watch rotation. As I walked down the ladder well, the adrenaline wore off and I got a bad case of the quakey knees. I had to use the handrail and take one step at a time.

The other guys asked me how I was. It was surreal—I don’t remember what I said, but I’m pretty sure we were having two completely different conversations. I finally got to use my flashlight to check out how bloody I was. I was surprised and relieved that it wasn’t much blood, mostly on my right sleeve and a bit on the front of my flak jacket. Thompson got a water can out and helped me wash it out. Then I cleaned my knife really well.

The rest of the night was fairly normal except I was in a bit of a fog. I never saw the guy or learned what they did with the body. Nothing else happened and at about 0300 we packed up and returned to the outpost.

I never talked about what happened with those guys again. It wasn’t until later that I began to ask myself the hard questions. I considered all kinds of scenarios. The most likely was that my attacker had been an Iraqi deserter who had camped out in the police station, waiting for the right time to walk south. Because I was wearing night vision goggles, I never really saw him, and in some ways that is a relief. When the stories about the conscripts and threatened families came out, I felt even worse about it.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

I also thought about how it is every young Marine’s dream to clear a building in enemy territory and kill with your bare hands. But the reality is very different—something no one would ever wish for.

I don’t like this story. Through all the years, I never told my family about it. I probably told only three or four friends about it, only after three or four beers too many.

Comments are closed.