A Chunk of My Life Was Taken From Me. You Could Say I Had a Bad Attitude.

When I returned from Vietnam in February of 1969 I had a bad attitude—a very bad attitude.

I joined the Air Force to escape college and a broken heart (another story entirely). It turned out that the discipline, order, and focus the Air Force provided was exactly what I needed, and for the first 18 months, I thrived.

My first duty station was an aircraft control and warning site on the northwest coast of the island of Luzon in the Philippines—100 airmen and contractors on a cliff above the South China Sea. Though there was nothing to complain about, we did manage to grouse about the isolation.

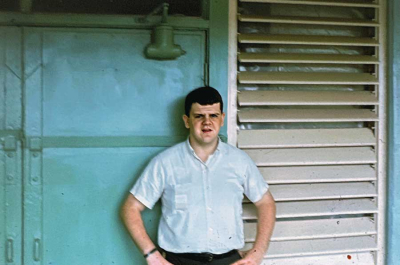

Ed Meagher in the Philippines in 1967. Photo courtesy of the author.

I found books and started a library (yet another story entirely). A mentor guided my reading, and I used the endless hours to devour books of every sort. The work I did was challenging and rewarding, and then I got to read sitting in a chair overlooking the South China Sea. I remember the feeling to this day—I was a kid who fell into a vat of chocolate and got to swim in it.

After seven months I transferred to Clark Air Base in Southern Luzon north of Manila. Despite tens of thousands of airmen and contractors and a far more hectic work schedule, I still found a quiet place to fall into books.

As I neared the end of my tour in the Philippines, I chose to go to Vietnam. To this day I have a difficult time talking about my time there. I was unprepared for the enormous responsibilities thrust upon me. The stakes were high, as high as they get. I wish I could have done better, been better. But I know I did the best I could at the time.

Still, I was different when I arrived at the Pentagon in 1969, and so was the world. Three years earlier, the radio had played Peter, Paul, and Mary, and hootenannies were still in fashion. Now, Grateful Dead and the Rolling Stones blared from boom boxes, and it seemed like everyone had just returned from Woodstock.

Meanwhile, I’d spent a year in fear of death or dismemberment. I couldn’t lower my perception of the threat level around me, and I couldn’t explain my feelings to anyone. Everything felt trivial, everyone around me out of touch with reality.

Military life stateside was also far different than military life overseas where the attitude was, “Do your job, stay out of trouble, and don’t be a slob.” We’d been too busy with real military operations to tolerate “chickenshit.” It seemed to me my Pentagon assignment was built solely on unadulterated chickenshit.

It started my first day on the job after a month at home. I’d spent two and a half years in fatigues or flight utility uniforms, and no one cared how they looked on me or anyone else. Now I reported to duty in my dress uniform for the first time since it was issued in basic training. It was a little ragged—no name tag or ribbon rack, and my sister may not have sewn on my new rank correctly. I couldn’t find my dress shoes, so I wore my jungle boots. I also needed a haircut.

Ed Meagher loved the first 18 months of his Air Force career at Wallace Air Station on the island of Luzon in the Philippines, now Naval Station Ernesto Ogbinar. From there, Meagher headed to Vietnam. By the time he arrived at the Pentagon in 1969, he had resolved to leave the Air Force. Photo courtesy of the author.

Most importantly, I didn’t want to be there. A month’s vacation convinced me I was done with the Air Force. A huge chunk of my life had been taken from me. I’d missed all the major milestones of my generation. In general, as I believe I mentioned, I had a bad attitude.

As I walked across the massive concourse in the Pentagon, I felt like a polar bear at a beach resort. I noticed several glances and double-takes. Then I saw a newly minted second lieutenant walking directly toward me. I tried to angle away from him, but he was coming for me. He stopped me with a sharp “Sergeant” that I couldn’t ignore, then asked my name.

I answered without using “sir” or “lieutenant,” and he called me on it. He told me I was out of uniform, and I agreed with him. He waited for an explanation, and when I didn’t give him one, he asked. Point in my favor. After I explained, he told me that was no excuse. I told him he was making me late for a meeting with my new commanding officer, wished him a good day, and walked away. I believe I may have mentioned that I had a bad attitude.

It didn’t go a lot better when I reported in. I met with a first lieutenant who may or may not have been my boss. He was about to dismiss me for the day when the squadron chief master sergeant burst into the office in a fit. He’d heard about me, and he very insincerely apologized to the lieutenant for my appearance, for my imposition on his valuable time, and for my very existence. He saluted the lieutenant, then turned and growled at me, “In my office, Sergeant, now.”

The rest of the day didn’t go a lot better. As the chief ranted and raved over my hair and jungle boots, I struggled not to laugh. I’d been in the culture long enough to know to agree with whatever he said and say as little as possible in response.

I had 12 months left in my military career, and I didn’t know how I would survive it. That’s when one of my many undeserved good karma gifts arrived in the form of Hap Arnold.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

I’d come to the Pentagon with a recommendation attached to my personnel record that the Air Force retain me. The service had spent a lot of money on my training, and I’d performed well for three years. As a result, I was assigned a retention counselor to convince me to reenlist for another four years. Hap was a retired Air Force chief master sergeant-turned-GS-11 Air Force civilian.

We hit it off when I noticed a Chicago Cubs banner in his office that said, “We’ll win the World Series next year.” We spent the first 15 minutes talking baseball. When we got down to business, I told him there was no way I was going to reenlist. He asked why and I vented for several minutes.

He listened quietly, then said, “Wow, I’m sorry to hear all that. How can I help?”

I told him how the Air Force had denied an off-base housing allotment, and that all my uniforms and baggage from Vietnam had been lost. Hap arranged for me to receive both the housing allotment and a uniform allotment. My biggest problem, though, was my assignment. I’d received a demeaning job with the worst possible schedule. He told me that might take a little while to fix, but he’d work on it as long as I lightened up on my bad attitude. We shook on it, and believe it or not, that is really the story I started out to tell.

A couple of weeks later I got a message to report to Hap’s office. We chatted for a few minutes, but it was clear from the look on his face that he had some good news for me. He had called in a favor; I was transferring to the Military District of Washington Command Post. That alone was an answered prayer, but Hap had more.

As Ed Meagher neared the end of his tour in the Philippines, he chose to go to Vietnam. To this day, he has a difficult time talking about that life-changing experience. Photo courtesy of the author.

He had gotten me assigned as the duty noncommissioned officer in charge of the entire Military District of Washington each weekend. It was an insignificant trash job that no one in their right mind would want, but he knew I would love it and I did. I worked 12-hour shifts Friday, Saturday, and Sunday nights from six p.m. to six a.m. No formations, no inspections, and no harassment. Just, “Do your job, stay out of trouble, and don’t look like a slob.” The transfer was immediate. When I reported for duty, I was most definitely “STRAC”—military slang for “a well-organized, well-turned-out warrior,” including a “high and tight” haircut.

The Military District of Washington is an artifact of the Civil War, formed to protect the capital. While it still serves that role, its duties are mostly ceremonial now. Most importantly, and for the purpose of this story, any active-duty service members who are not under orders from their command and find themselves in the Military District of Washington also find themselves under its command. I served as the single point of contact for any problems that arose during the weekend or for any active-duty servicemember who wandered into the Military District of Washington. And they did wander in, for several reasons, including to frequent one of the dozens of after-hour night clubs in the southwest quadrant of Washington where “blue laws” were unofficially relaxed.

Everything about these clubs was conveyed by word of mouth. Some were known for their music or dance bands, others for their class and decor. All were known for their booze, and many were known as strip clubs, or “titty bars.” These places attracted the most military personnel who came to the Military District of Washington.

My job was simple. By six p.m. on Fridays, we settled into a trailer with four phone lines. One was an open line to the command center. Another was a direct line to the military police office at Fort McNair in southeast D.C. The third was a line to the Metropolitan Police District Six front desk. The fourth line was the most interesting. It was a regular D.C. phone number that was very quietly given to the owners, bartenders, and bouncers of these illegal-but-tolerated after-hour clubs with the understanding that they’d call it for a resolution if there was ever an issue with a G.I.

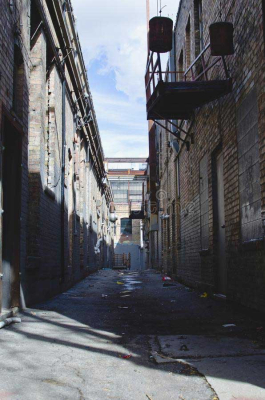

An alley in the southwest quadrant of Washington, D.C., in 1970, where “blue laws” were unofficially relaxed. Service members frequented the bars, nightclubs, and strip clubs here—and from time to time got into trouble. That’s when Ed Meagher, the duty noncommissioned officer in charge of the entire Military District of Washington each weekend, was called. Photo courtesy of the author.

The first calls came in around 10 p.m. Every call was unique, but in truth, they were the same: Pfc. or Sgt. or Lt. So and So had gone to a club, had several drinks, engaged in conversation with a lovely young lady, bought the young lady several glasses of champagne, and then suggested they continue the evening in a less public place. Often at this point, the lovely young lady would lose interest and head backstage, and the soldier, sailor, airman, or Marine would receive a bill that approached their monthly pay. Harsh words were exchanged, followed by various forms of martial arts. While these warriors displayed some courage and even skill, it always resulted in them being handcuffed to a wall in a closet or storage room in the back of a club, where inevitably this mysterious phone number was written on the wall.

That’s where I came in.

Two large, newly minted, temporary military police officers and I would head to this location. We first checked on the physical condition of our combatants. Most bouncers stopped short of great harm for fear of sending them to a hospital, and the ensuing, inevitable questions. If their injuries did not appear life-threatening, we moved on to the next phase. This involved collecting all the money the G.I. had in his possession.

I required them to turn their pockets inside out and take off their shoes and socks. I took the money, met the bar owner or manager, and offered whatever it was to settle their bills. There was no real negotiation; either they took it or I’d call the cops and let them sort it out. Since involving the police was a nonstarter, the negotiations ended, and we moved on to phase three—often the most difficult.

Dealing with still-drunk combatants who often outranked me and wanted a second round with the bouncer was never easy. Before I had them released from the club’s bracelets, I told them their best option was to go quietly back to our trailers to sort out this injustice. Most did, after some heated discussion, but every once in a while, I needed the muscle provided by our two young and eager military police officers.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

Once back at the trailer, we sorted them into a holding cell, a cot, or a vomitorium in the back. At about five a.m. we woke them, and I told them I was just the greatest guy in the whole world and they could return to their units without any record of their indiscretions, or I could drive them in handcuffs to the stockade at Fort Myer to deal with the full force of the military justice system. Only one to my memory, a young Marine lieutenant, chose the second option.

This detail saved my military career. It filled all my needs at that point in my life. Strange as it may sound, I found it rewarding, and most importantly it got me over my bad attitude.

Comments are closed.