After nearly 100 years, scientists solve puzzle of ancient predator’s skull

After almost 100 years spent puzzling over the crushed fragments of a 330 million-year-old species’ skull, scientists have successfully pieced together the fossilized puzzle to reveal what the skull looked like, according to a new study published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology.

Several skulls believed to have belonged to the ancient predator, known as Crassigyrinus scoticus, have been found in Scotland. The first specimen was recorded and named Crassigyrinus by David Meredith Seares Watson in 1929, but the specimen only showed parts of the right side of the skull, with only the cheek region and the side of the snout, making it difficult to unravel how the skull looked in its entirety.

Crassigyrinus has been known for nearly a century from several specimens, but these are all deformed and damaged. We used micro CT scanning to image four skull specimens from @NHM_London and @BritGeoSurvey and digitally prepped the skull, revealing new anatomical data. pic.twitter.com/oMUuzmdF7Z

— Laura Porro (@LauraBPorro) May 2, 2023

Crassigyrinus is noted for being somewhat odd, having some unusual characteristics.

The species was a stem tetrapod, a group of four-limbed animals among the first to move from water onto land. Crassigyrinus, unlike its relatives, remained an aquatic animal, although it is unclear if this is because its ancestors returned from land to water or never moved to land.

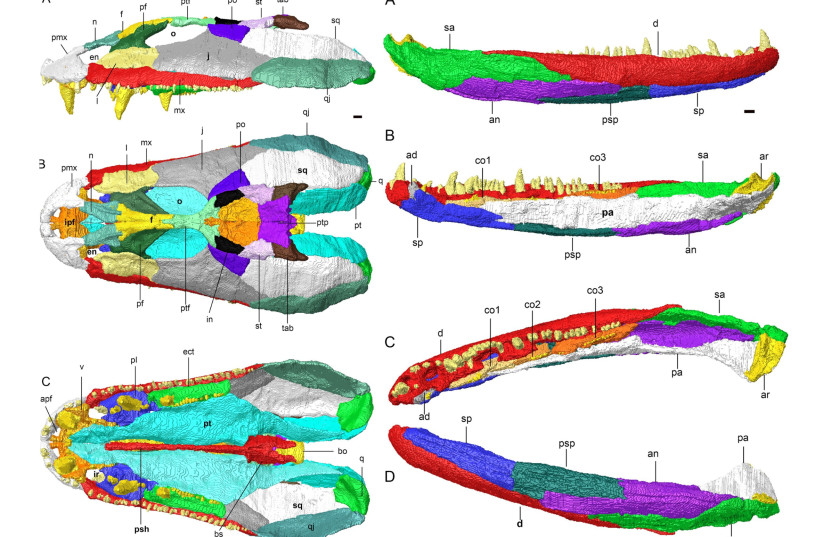

3D reconstruction of the cranium and lower jaw of Crassigyrinus scoticus (credit: Laura B. Porro, Emily J. Rayfield and Jennifer A. Clack/Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology)

3D reconstruction of the cranium and lower jaw of Crassigyrinus scoticus (credit: Laura B. Porro, Emily J. Rayfield and Jennifer A. Clack/Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology)A feared predator

Crassigyrinus would have likely been a feared predator in its day, as it would have been about two to three meters long and behaved somewhat like a modern crocodile. The species’ skull contains several ridges which would have helped to strengthen its skull and spread the force of its bite between many teeth.

The species also likely had large eyes that could see in the dim environment of the coal swamps and an odd gap near the front of its snout that may have had some as of yet unknown purpose, with one possibility being that the gap was used for helping it to detect electric fields or chemicals.

“A lot of early tetrapods have midline gaps at the front of their snout, but the gap in Crassigyrinus is much larger and features smoothly sculpted edges,” explained Dr. Laura Porro of the University College London, the lead author of the study, in a press statement by the Natural History Museum. “The nostrils were elsewhere, so there has been a lot of speculation about what this opening might have been.”

“A lot of early tetrapods have midline gaps at the front of their snout, but the gap in Crassigyrinus is much larger and features smoothly sculpted edges.”

Dr. Laura Porro

The species lived in coal swamps in what is now Scotland and parts of North America, which preserved their skeletons, but did not provide much structural integrity, leading to the fossils being squashed over time, with the ones shattered into many pieces, flattened and laid on top of one another. The rock they were preserved in does, however, provide great contrast for CT scanning.

Modern technology paints a new picture

While early studies suggested that Crassigyrinus had a very tall skull like an eel, with a short and broad snout, advances in CT scanning and 3D visualization have created a different picture.

“When I tried to mimic that shape with the digital surface from CT scans, it just didn’t work. There was no chance that an animal with such wide a palate and such a narrow skull roof could have had a head like that,” explained Porro. “Instead, it would have had a skull similar in shape to a modern crocodile, with its huge teeth and powerful jaws allowing it to eat practically anything which crossed its path.”

The researchers used CT scans from four Crassigyrinus specimens which together included all the bones of the skull. They then began what Porro described as a “3D jigsaw puzzle.”

“I normally start with the remains of the braincase, because that’s going to be the core of the skull, and then assemble the palate around it,” explained Porro. “This gives me a base from which I can start building upwards, using overlapping areas of bone known as sutures which provide hints about how the skull bones fit together. As the bones were broken, rather than bent, we could reconstruct the specimen with a good degree of confidence.”

Porro noted that the new study is dedicated to co-author Prof. Jenny Clack, a paleontologist who revolutionized the field’s understanding of the early evolution of tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates).

“It is bittersweet to finally see this paper published,” said Porro. “Jenny Clack worked on it as her PhD, and I’m glad she was able to see the final reconstructions of Crassigyrinus. She was so inspirational, and I would have loved to continue working with her for years to come.”

Comments are closed.