‘Embrace the Suck’–Life as a Gold Star Child is a Race With No Finish Line

It’s Saturday morning in Lynchburg, Virginia, shortly before sunrise. I lace my Nikes and head out the door for a weekly run with my dad. I’m 12 years old.

I tiptoe down the steps and gently open and close the front door so I don’t disturb my mother and siblings, still asleep in their beds. My father and I hop in his 1984 Jeep Cherokee and cruise to the foothills of the Blue Ridge mountains. The sound of Mumford and Sons blares from the speakers as the cool wind blows through our hair.

When we arrive at the base of the trail, the sky is split into deep blue and orange streaks—the afterglow that appears for only a few minutes after sunrise.

Bailey Donanue and her dad, Mike, run along a trail in August 2014. Photo courtesy of the author.

I follow his lead. As we jog down the path, our legs fly over roots and leaves as the sound of our footsteps and breaths echo in sync along the winding trails. A couple of miles in, he points to one mountain, Sharp Top, as we stretch at an overlook.

“Look, Bailey!” he says.“That’s your mountain.”

A few miles later, when fatigue kicks in from the altitude, he repeats the same words he always says when grit is required more than ever before.

“Embrace the suck.”

When my father and I arrive back home, he begins making breakfast. The smell of pancakes and coffee blends with the sounds of Pearl Jam. My brother, sister, and mom slowly gather at the dining room table. We eat, make a plan for how we want to spend the day, and then leisurely stack dirty dishes into the dishwasher.

The time I spend with my dad is rare but intentional, like wearing the necklace he gave me from Iraq when I turned 10, brittle from age and reserved for the most special occasions.

I am always happier when I’m with him, especially on the days he drops me off at school because they are so rare. They mean he isn’t at work or deployed to another combat zone. It means more time with my partner in crime.

And it means one more ride in his beat-up, faded-from-the-sun Jeep, and looking at him behind the driver’s seat saying three words I can still hear.

“Do good things.”

* * * *

It’s a Tuesday afternoon on Sept. 16, 2014. I am 16.

The day ended 10 minutes ago, but I’m working on an extra credit assignment with my brother Seamus, who shares a history class with me. When it’s over, we walk down the hall and through the side doors of our school, laughing over stupid jokes before we go our separate ways. He has cross-country practice, and my mom is picking me up. She is never late.

Five minutes pass. I begin to worry.

Another five minutes pass. Now I’m scared.

Now 15 minutes have passed.

I call her cell phone.

No response.

Another five minutes pass. Silence.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

After 25 minutes, I begin pacing the sidewalk.

30 minutes. Still. No. Response.

I call again and again. My mother finally picks up.

I can feel her tears as she tells me a family friend will pick me up. She says she has to stay late at work.

I know she is lying.

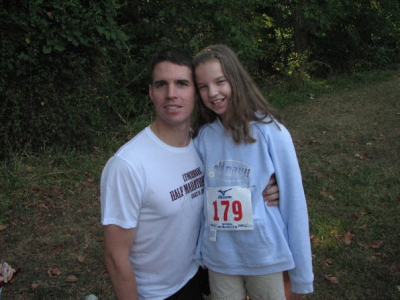

Bailey Donahue, age 11, poses with her dad’s race bib. Photo courtesy of the author.

Our conversation is abrupt. She tells me she loves me.

I call my best friend, Jesse. “I hope this doesn’t have anything to do with my dad,” I tell her.

A few minutes later, my mom’s friend arrives. I pelt her with questions.

I know something is wrong.

She tells me she doesn’t know. That she doesn’t have answers.

I know she is lying. I worry that my dad is dead.

Then, as we round the corner of my street, I see a strange car in my driveway. And I know.

It takes me only a few steps to get to my front door. I turn the door handle with the greatest hesitancy that my body can allow. That’s when I see two men in uniform standing in my living room.

My mother is on her knees, kneeling atop a carpet my dad sent us from Afghanistan.

“You have the wrong guy,” she cries out. “I know he’s out there hiding, you just have to go find him!”

I walk towards my mom and wrap my arms around her.

In my head, I see a montage of future moments flash in my mind. College acceptance. Graduation. The flat tires and car problems he’s supposed to help fix. Getting my first job. Walking down the aisle on my wedding day. The marathon we were supposed to run together.

But this time, without my dad. All taken away by a Taliban fighter.

Mike Donahue in Afghanistan in 2014. Photo courtesy of the author.

After a few seconds, I let go of my mother and slowly walk upstairs to my room. I shut my door and sit on my bed.

Time stops. All I can hear is the watch on my bedside table.

Tick. Tick. Tick.

The minute hand moves forward without me. I sit for a while without moving. I stare blankly.

My mom’s friend slowly opens my door and embraces me. I begin to feel my body again. She ushers me downstairs as our house fills with family, friends, and strangers. My mom is on all fours on our front lawn, throwing up as our casualty assistance officer drives down the street and parks in our driveway.

Next, I see Seamus walk through the front door. His eyes are the saddest I’ve ever seen them. I walk back upstairs, wanting to hide from it all.

My dad was supposed to be home already. But he was involuntarily extended for 30 days. He had just 23 days of his deployment remaining.

Time passes.

I hear the house pile with more people. More time passes. I isolate myself from it all.

Mike Donahue hanging out with kids around the Um Eneej village outside the old Radio Relay Point 10’ in Iraq in 2008. Photo courtesy of the author.

From my bedroom, I hear my brother and another family friend leave to pick up my older sister, Victoria, from college in Boone, North Carolina. My mom’s greatest fear was that my sister would find out about our dad from someone else, so she’d told her over the phone—only after telling my sister to hand the phone to her roommate.

“I need you to step into a different room and let me know when you have. I’m about to tell Victoria that her father is dead, and I need you to be by her side until we can pick her up so she’s safe.”

I lay on my bed beneath the sheets. I listen to the watch on my bedside table again.

Tick. Tick. Tick.

* * * *

It’s Wednesday morning. My first day waking up as a Gold Star child. As I open my eyes, I think my dad’s death was just a nightmare.

Then I hear my mom’s sharp reverberating cries and I remember our new reality.

Moments later, a family friend enters my bedroom. We have to fly to Delaware for my dad’s dignified transfer. I sit on my floor and stare blankly in my mirror. My mom’s friend brushes my hair. She tells me I’ll look beautiful.

The dignified transfer of Mike Donahue on Sept. 17, 2014, at Dover Air Force Base, Delaware. Photo courtesy of the author.

I feel nauseous.

Later in the day, as the plane’s wheels on our commercial flight lift from the tarmac, tears stream down my face. I hope the flight will crash.

As my family and I arrive at a hotel, my mom talks to the widow of someone killed alongside my dad. She has two children. One is a young daughter.

I sit with her, broken by her youth. She is 9 years old.

We eventually drive to Dover Air Force Base and are shuttled to the tarmac. We wait.

When the tail of the plane opens, six uniformed men march onboard and carry my dad’s flag-draped coffin from the aircraft to American soil. It’s dark outside except for the lights illuminating the runway. A spotlight on the dream I can’t wake up from.

We stand in silence until my mom points out a butterfly that has landed on my dad’s casket. It is in the direct light. You can’t miss it. I smile.

As they carry him to the vehicle, the butterfly flits away.

The next two weeks are a blur, and before I know it, I’m looking at my dad in his casket. He looks real and absent at the same time.

Until now, none of it felt real.

Later, the awareness of his absence grows as I hear the sharp, hollow sounds of horses drawing louder on the roads between fields of green and rows of white, leading my father’s flag-draped silver box into Section 60.

When the horses come to a stop, eight men in uniform lift his casket and march in synchronicity. They set him down a few feet away from rows of chairs. Red roses mark our seats.

The funeral of Mike Donahue at Arlington National Cemetery. Photo courtesy of the author.

When the chaplain begins to speak, all falls silent. His words are beautiful, but I can’t process them. I am beginning to realize that I will never see my dad again.

A soldier plays “Amazing Grace” on the bagpipes. A retired soldier places an 82nd Airborne medallion on my dad’s casket.

Seven men in crisp uniforms each fire their rifles three times. A bugler plays taps.

An officer kneels down and presents my family with a folded American flag, an honor I don’t wish to receive. I can’t accept that he’s a few feet away from me, waiting to join a sea of white stones and perfectly cut green grass. I don’t want to walk away.

My father, Mike Donahue, is dead.

* * * *

It’s a Wednesday in May. I’m 25 years old—the age my dad was when I was born.

It’s just before sunrise when I put on my Hokas and tiptoe over the creaky wood of the cabin I’m sharing with others, careful not to wake them. I gently open and close the front door, then walk down the steps and stretch.

I follow the dirt path that leads to the end of the ranch, the sound of my dad’s playlist blaring in my headphones as I run alone down a Texas road. With each step, the sky splits into deep blue and orange streaks—the afterglow that appears for only a few minutes after sunrise.

A few miles later, when fatigue begins to kick in, I hear the same words my father would always say when grit was required more than ever before.

“Embrace the suck.”

Bailey Donahue runs a marathon in honor of her dad alongside Wear Blue in San Antonio, Texas, in December 2021. Photo courtesy of the author.

For years, I’ve felt like people are temporary, like the whispers my brother and I heard in the hallways when we returned to school two weeks after my dad was killed. I hated that. I hated the announcement my school made over the intercom and the condolences texts sent by strangers. I hated seeing my mom cry. I hated that I couldn’t focus in class or bear to think about taking the SATs or where to apply for college. Or how I tried to hide my pain for so long that I no longer recognized myself.

After running the Marine Corps Half Marathon alongside Wear Blue, Bailey’s brother, Seamus Donahue, leaves his medal at his father’s gravesite. Photo courtesy of the author.

I hated that I was afraid to take up any space at all until I filled my space up so much that I didn’t have room to feel anything anymore. Worst of all, I hated myself. So much that I considered how much easier it’d be if everything just stopped.

I push on under the vast Texas sky.

I remember the military bases as playgrounds, the paracord bracelets I wore as jewelry, and traveling through cardboard box tunnels with my brother when the Army moved us into a new home.

I begin to realize the gifts my father has given me, even in loss. Because of my dad, I recognize the individual value of every person I meet. Because of my dad, I live my life with intention and purpose. I connect more deeply with people. Because of my dad, I know the finiteness of life and the importance of the words spoken about your character when your life comes to an end.

Sunrise at the Lucky Spur Ranch in Justin, Texas, where Bailey Donahue joined other Gold Star children and siblings for a week-long writing seminar in May. Photo by Bailey Donahue.

Because of my dad, I graduated from college debt-free and now serve families like mine through the Children of Fallen Patriots Foundation. I have met friends who also lost a parent, and I ran my first Wear Blue marathon with them. Because of my dad, I met President Joe Biden and first lady Jill Biden and asked her what advice she had for a 24-year-old.

“Be kind,” the first lady told me. “Always be kind.”

I cannot change the fact that I lost my father. But I can learn to love where I am and find meaning while sitting in discomfort. Above all, I can find the good in every day.

I can embrace the suck. It’s the duality of fullness and emptiness at the same time. Often, it’s being in two places at once. On one hand, I’m stuck with the grief of losing a piece of myself. On the other, I’m hungry to grow older, to take all that life has to offer.

Living without him is a race that never ends.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

Some moments, I feel my feet strike the pavement paired with an inner fullness of purpose and direction. In other moments, I’m on the side of the road, hunched over on the curb with my heartbeat throbbing in my ears and my mind trying to convince myself I can’t make it to the next light post.

I keep running. Not running away. Not running to. But running with.

Comments are closed.