A Close Encounter With a Little Red Car and an Accusation of Attempted Murder

I think of Haiti as a country that just can’t catch a break. Beyond environmental challenges—deforestation, hurricanes, earthquakes—violence is commonplace, exacerbated by crushing poverty, crime, gangs, and drugs.

Throw in the country’s history of corrupt and dictatorial regimes—including decades of exploitation by France in which Haiti was forced to pay billions of dollars for its freedom—the small Caribbean nation has never had a chance to get out of the starting blocks.

In 1991, Jean-Betrand Aristide became Haiti’s first democratically elected president. The victory was short-lived; eight months later, Aristide was overthrown in a military coup. Under U.S. pressure, Aristide was reinstated in 1994.

I arrived against this turbulent backdrop in the fall of 1995 as part of the United Nations Mission in Haiti. We’d come for the historic elections between President Aristide and René Préval and the first peaceful transition of power in Haiti’s history.

David J. Fugazzotto Jr. at Jeremie International Airport, Haiti. Photo courtesy of the author.

I was a new company commander, deployed in support of the 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault). My company was part of the medical task force providing care across the country at three locations. The teams were primarily there to support UN partner forces, but we also periodically treated local Haitians when life, limb, or eyesight was involved. It was very difficult to turn locals away; with a physician, dentist, and physician’s assistant, as well as medics, X-rays, and basic laboratory services, the care we could provide was sometimes better than what was available locally.

While I normally stayed with my headquarters section in Port-au-Prince, I tried to get out to see my soldiers as frequently as possible—usually a couple of times a month. Sometimes I could get a ride on a helicopter, but being just a wee captain, I didn’t often rate a seat. So I spent a lot of time on the roads in our white, UN-emblazoned Humvees.

As 1995 came to a close—and following the Dec. 17 election of Preval—it was time to make the rounds again. I loaded up with three of my troops: Staff Sgt. Heath, Sgt. 1st Class Roth, and Spc. Shinkle. We planned to spend the night at the camp in Gonaïves with one of my platoon leaders and her soldiers there before heading up to Cap-Haitien in the far north to ring in the New Year.

About a half-hour out from Gonaïves, in the middle of rice farming country, a little red car tried to pass us on the left. If you’ve ever been to Haiti, you know that the roads leave much to be desired. As the car came up alongside our truck, it ran off the left side of the road. The shoulder of the road was about three or so inches below the road surface, and the tires slipped and struggled to get a grip on the pavement. Finally, the tires caught enough traction and shot the car across the road, missing us by inches. It was sheer luck and Spec. Shinkle’s reflexive stomp of the brakes kept the car from slamming into us and most likely, at that speed, killing us.

Rice fields near Gonaïves, Haiti, where David Fugazzotto was headed when he encountered a little red car. Photo courtesy of the author.

Tires screeching, the little red car careened across the road as the driver tried in vain to regain control, finally going airborne into a drainage ditch along the side. The impact threw up a huge wave of water, nearly flipping the car end over end. If the water hadn’t been there, it would have been disastrous. As it was, the car teetered on its front end before slamming violently back down into the ditch. All the windows exploded outward with the impact.

By this time, we had stopped. Leaving Spc. Shinkle and his M16 to guard the two vehicles, the rest of us ran back to assess the damage. As we got to the crash site, the passengers had already gotten out of the car. Unbelievably, nobody was dead. Even more unbelievably, no one was even seriously injured. Bruised and bloodied, but amazingly OK.

This is where the story takes an unforeseen turn—and becomes the kind that stays with you more than a quarter of a century later. Simply put, I never had any overly traumatic experiences during my service. I’d had many moments when I’d felt scared, but as far as I know, I’d never been in anyone’s gunsights. A few “run into the bunker” moments, but that was it.

Remember, now, that the little red car had come flying around us.

An irate woman climbed out of the wreckage, accusing us of running them off the road.

“You tried to kill us!” she shouted.

“What the hell are you talking about?” I asked, incredulously.

“You did that on purpose! You assholes!!”

Her command of English was surprising, especially those words not common to polite conversation. This was no polite conversation.

“You UN are supposed to be here to help us, not to kill us!” she screamed.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about! You almost killed us!” I said. “The way you guys were driving all over the road, it’s a miracle we didn’t end up in that ditch!”

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

As she ranted, she got more and more animated and pushed up in my face. The three of us began to get a bad feeling. Despite the success of the recent elections, riots were not uncommon in Haiti, and the last thing we wanted to do was get involved with one.

Left to right: Capt. David Fugazzotto, Staff Sgt. Teri Heath, 2nd Lt. Mike Hulsey, Spec. Chris Shinkle, and Sgt. 1st Class Steve Roth, the group that would encounter the little red car on the second to last day of the year in 1995. Photo courtesy of the author.

Already, people materialized out of the fields. It was like a scene from Children of the Corn. Close to 30 people crowded around, watching the spectacle unfold. It was just a matter of time before the newcomers would start choosing sides.

As the lady kept coming at me, stabbing her finger at me like a weapon, Staff Sgt. Heath, my 105-pound, 5’2” training sergeant, wedged herself between us.

“You take a step back,” Staff Sgt. Heath said, “or I’m gonna get angry. You wouldn’t like me when I’m angry.”

“She’s right,” I said. “You really wouldn’t. You should trust me on this.”

“Fuck you!” she said furiously, “Fuck you! How am I going to get to Cap-Haitien?” she asked. “We have to go to a wedding!!”

“Hey, that’s not my problem,” I said. “We didn’t cause this accident, and since you’re all OK, we’re leaving!” I turned to my soldiers, and said, “Let’s get out of here.”

Our rules of engagement could be pretty much summed up in the catchphrase: “If you beat ‘em, you treat ‘em.” In other words, if we caused an accident or injury, we took responsibility.

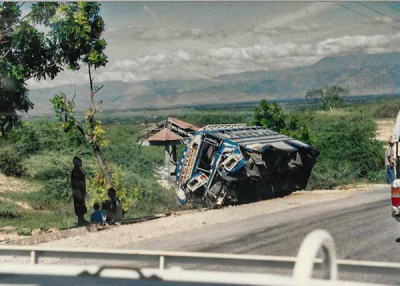

A wrecked tap tap, an all too common sight along Haitian roads. Photo courtesy of the author.

But we hadn’t been responsible, and we needed to leave before the situation got worse. We’d already put ourselves in a potentially dangerous position by stopping. We turned and resolutely walked past the still-steaming wreck to our Humvees. Shinkle was dutifully guarding the trucks but by now looked pretty nervous. As we moved back to the car, the woman and her group matched our every step, yelling that we’d deliberately run them into the ditch.

“Look, you guys are alive and relatively unhurt,” I told her. “We can’t do anything else. As soon as we get to the next town, I’ll notify the police, and they’ll help you. Now, we’re leaving.”

We loaded up, started the trucks, and headed out. She chased us, cursing and raving furiously until we couldn’t see her anymore.

As we came into Point l’Espere a few miles down the road, we passed a Haitian policeman on a bicycle. I flagged him down and told the officer in my best junior high school French: “Il y’a un accident. Quatre blessé, mais pas de morts. Là- bas, peut-être 15 minutes.” (There’s an accident. Four hurt, but no dead. That way, about 15 minutes). Merci, Madame Downs!

He nodded and leisurely pedaled off in the general direction I’d indicated. Having kept our word, we drove on.

About 30 minutes later, we arrived at the camp in Gonaïves. Immediately, I called the task force tactical operations center back at Port-au-Prince and let them know about the incident. Figuring it was best to cover ourselves, we all wrote up affidavits to fax back to the base.

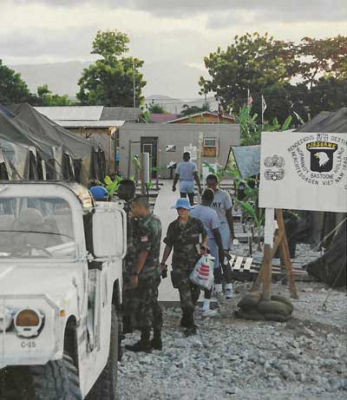

C Company, 426 Forward Support Battalion base camp, Gonaïves. Photo courtesy of the author.

“I seen this little red car shoot across the road …” wrote Sgt. Heath, and the grammarian in me cringed. I’m pretty sure she did it on purpose.

We faxed the statements down to Port-au-Prince and spent some time letting the adrenaline wear off. Though I am not a smoker, that day I almost became one as I enviously watched Sgt. Heath and Spc. Shinkle chain smoke a pack together.

While we decompressed and reflected on the adventurous trip up from Port-au-Prince, a captain from the Special Forces unit also based at the camp walked up to us.

“What’s up?” the snake-eater said. “There’s a really pissed-off lady at the front gate who says a UN vehicle ran her off the road south of here. You guys know anything about that?”

“Um … did she say what the vehicle looked like?” I asked.

“White Hummvee, UN markings … like those over there.” He pointed at the trucks we’d just come up in.

“Really?” I said. “That sucks. Although I doubt any UN people would deliberately run anyone off the road. UN troops are here to help the Haitians, not to kill them, you know.”

“She wants to make a formal complaint to the UN,” he said. “For attempted murder.”

“I see,” I said. “Attempted murder … that’s, um, that’s pretty serious. Does she have any proof?” I asked.

“I’m not sure,” said the Special Forces captain, “but I’ll tell her you’re not here.” He grinned and walked off.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

The four of us looked back and forth at each other, and started laughing, realizing that we were now on the lam. Fugitives at large. Wanted for attempted murder, no less. We pictured our faces on wanted posters across the country at Haitian post offices.

Ultimately, nothing ever came of the close encounter with the Little Red Car, and we eventually made it up to Cap-Haitien to ring in the New Year with my other platoon leader and troops, keeping a sharp lookout for our furious friend the whole time.

Comments are closed.