An Interview With Ai Weiwei, Part One: The Year 2008

An Interview With Ai Weiwei, Part One: The Year 2008

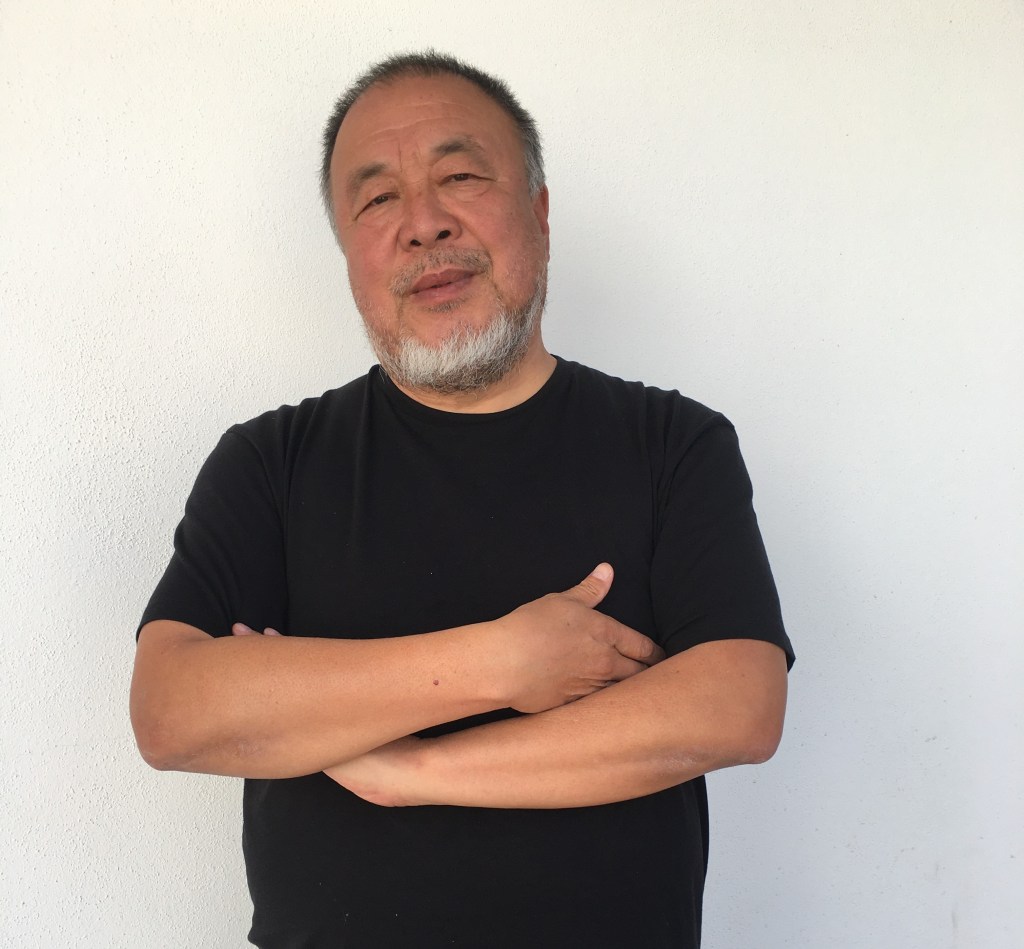

I interviewed Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei in May in Portugal. It was my first meeting with him, and as many Chinese activists do, I called him by his nickname “Aunt Ai” (“艾婶儿”). Out of the hundreds of interviews with Ai Weiwei, I hope readers find this one worthwhile. The interview will be posted in three parts: “2008”; “Rebar and Water Lilies”; “China, the World, and Freedom.” — Yaxue Cao, editor of China Change

2008

Yaxue Cao (YC): Let’s start in the year 2008. I think it’s impossible to discuss present-day China without talking about 2008, and no discussion of 2008 would be complete without mention of Ai Weiwei. Let’s think of China in 2008 as an exhibition on display for the world — not just by the Chinese authorities, we could use a line from your memoir as the title: “Two Different Worlds, Two Different Dreams.” I’ve interviewed various people, and always asked them their experiences and thoughts on 2008 whenever relevant. I’d like you to expound a bit on this “exhibit” that China put on for the world that year.

Ai Weiwei (AWW): Thank you. As regards 2008, I have to start with my return to China in 1993. For 12 years before that, I was in America, so that’s the larger background. Before I went to the U.S. in 1981, I spent most of my time in Xinjiang. I enrolled in the Beijing Film Academy from Xinjiang, but went to the U.S., and eventually returned to China in 1993.

In the decade from 1993 to 2003, and then until 2005, for a total of another 12 years, I was basically idle. However, in the year 2000, I got into architecture, or rather, I built my own studio, which I guess people would call “doing architecture.” After that, I suddenly developed an interest in design and architecture, probably because I had my own perspectives on things like architectural style, and it also happened to be a period when such discussions were particularly popular in China. It was a time when new lifestyles were emerging, or China was rebuilding the stage for new shows, so to speak, and there was a great void in the market of ideas, be it aesthetic, ethical, or philosophical.

So as someone like me, who worked with contemporary art and had spent over 10 years in the United States, coming back to China and building my own studio was quite an impactful event in the kind of market environment that Chinese were used to, so many people are interested in hearing my perspective on this issue. The process afforded me opportunities to connect with society because previously I existed as an individual artist, but after getting involved in architecture, I entered the public arena. Obviously, architecture involves a wide range of interactions. It involves planning, relationships with the government, with design teams, structural designers, and construction partners. It’s itself a small society, and one that is highly politicized and bureaucratic.

So all of a sudden, I went from being a lollygagging person to someone highly regarded for discussing issues like aesthetics, lifestyle, and artistic forms. As a result, I started giving interviews, and at the same time, I also got involved in a major state project — the design of the National Stadium for the 2008 Olympics. It was an opportunity I came across quite serendipitously, but we’ll talk about that later.

Around this time, something crucial happened. In 2005, Sina Blog invited me to be part of their so-called celebrity blog section. They knew that I represented a new lifestyle in a way, as there was no one else who had my understanding of both China and abroad, particularly as concerned contemporary culture. I told them that I had never used a computer before and didn’t know how to type. They reassured me, saying things would be fine and that they would help me learn. I had no understanding of the internet or what it could do, or what I could possibly need it for. So they helped me set up a blog.

It was quite a challenge for me to write my first blog post because I didn’t know who my audience was or what to write about. I ended up writing just two lines, which was just one sentence: “Expression requires a reason, and expression itself is a reason.” I wrote those words on paper and asked my assistant Xu Ye (徐烨) to type and post them on the blog. That was my first post. After that, I started receiving a lot of feedback, and that’s how I began blogging. I read Beijing News (《新京报》) and other subscription materials every day, and based on what events were going on, I wrote my reflections about them.

I am someone with strong viewpoints. I might have a biased perspective, but I always have one and plenty of opinions that come with it. Once I get started, it’s unstoppable.

One of the most memorable incidents I remember involves one Chinese medical academician named Zhong Nanshan (钟南山), who had lost his laptop. The Guangzhou Public Security Bureau swiftly solved the case and recovered the laptop. Zhong claimed the contents of his laptop were worth several hundred million yuan, which I guess contained information related to public health matters. In the news he mentioned that the custody and repatriation system (收容遣送制度) for the so-called “migrating population,” which had been abolished after the death of Sun Zhigang in police custody. He suggested something to the effect that this system should be reinstated, with the implication being that tolerating “bad” people would harm the “good” people, or something along those lines. Reading about that really enraged me. I felt that as an elite intellectual in China, a member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering (actually as I would later find out, none of the academicians in China are worth the title), he lacked even the most basic moral and ethical bearings that should exist in society. So, I wrote a post titled “A Billion-Dollar Laptop and an Irreparable Human Brain,” in which I raked Zhong Nanshan and the cultural group he represented over the coals. The article was rather brutal and, in retrospect, hilarious. However, the next morning, I woke up to find that it had been shared over 200,000 times. With such massive dissemination, I suddenly realized the power of the internet.

After that I wrote many similar articles, which were also widely shared. Before long, I became a popular blogger on Sina. However, this phase didn’t last very long.

In the run-up to the Olympics, as I was involved in the design of the main stadium, a reporter asked me if I would participate in the opening ceremony. I remember it was in 2007, and I said that I wouldn’t participate in the ceremony because I believed the whole Olympics was a farce. It had been turned into a propaganda feast to glorify the Party, attributing all of China’s development to the CCP alone.

My biggest displeasure came from the fact that before the Olympics, it had already been communicated [by the authorities] that the best way for Chinese citizens to support the Games would be to stay at home and watch TV, and keep off the streets; and migrant workers in China’s cities were advised to return to their hometowns. This brought back the memory of mass performances fabricated by the central authorities in their attempts, in this case, to beautify the so-called achievements of China’s reform and opening up.

All this was really terrifying as far as I was concerned, so I expressed some criticism of it. But to my surprise, the Guardian’s headline on the subject would go so far as to say something like “man behind bird’s nest stadium to boycott games.” In reality, I was just expressing my opinion and didn’t say anything about boycotting it. I merely said I wouldn’t participate in it.

But of course, once such a headline appeared, I became the center of attention again. It seemed that the whole world was applauding the Beijing Olympics, and I felt that NBC in the United States and others were cooperating with, and singing the praises of, the Chinese Communist Party. The whole world was cooperating with the CCP, wanting to put on a fabulous show, because for the CCP — or for China — the two to three decades leading up to 2008 was actually a celebration of globalization. It was the largest-scale predatory carnival in human history that the West had seen, whether in the age of colonialism, or in the pre- or post-World War II era. Nobody had seen a pit excavated so deep and so large before. And when everything came flooding in, it really was an ocean of turbulence.

The Communist Party had decided to allow some people to get rich first as the regime faced imminent collapse. I wrote a number of blog posts as regards this political platform, if it can be called that. I said that everyone in the countryside who knew how to stand upright all became security guards in the city, and young women who were even slightly attractive all went to massage parlors, and people would be anything to make money. All ethics were thrown to the wind, undermining China’s culture and everything else. It has been the case since.

I was among the earliest to understand and criticize these issues. In fact, I keep saying that I’m not against communism, but against China. By “against China,” I mean that I believe the fundamental problem of China lies not with the Communist Party alone, but that China’s culture and history have been destroyed. While the Communist Party is largely responsible for this destruction, the nation as a whole is in fact in a period of tremendous decline. It’s more or less irredeemable, and there is no need to salvage it. It’s best to let it die.

So, at that time, I was a very impassioned person and constantly brought up these issues. This, of course, pushed me to the forefront [of public attention] because of my visibility and the fact that I never hesitated to speak my mind. It is in this context that our scene, the year 2008, begins.

Speaking of 2008, we also can’t ignore the era of Jiang Zemin that preceded it. Jiang was actually a very pro-foreign and westernized person. He didn’t believe in the building styles constructed by Chinese academicians and architects. His first priority was to build the National Centre for the Performing Arts, and he commissioned Paul Andreu from France to design it. Having a taste for western excellence, Jiang Zemin knew very well what was good and what was not against the backdrop that China’s institutions had been modeled on those of the Soviet Union and deeply entrenched in the politics of the Communist Party; and the various academies were dominated by conservative academicians. The central leaders were mostly laymen and had to rely on the academicians for almost everything. These academicians thus can be summed up as the main evildoers in China, knowing that the top leaders had no one else to rely on and had to listen to them, so they enjoyed even greater influence than some provincial leaders. In such an extremely bureaucratically corrupt society, the National Centre for the Performing Arts faced opposition from numerous academicians. They signed a joint letter criticizing the design, describing it as “an egg” and using vulgar analogies, saying it was inappropriately located next to the Great Hall of the People. However, in the end, the central government stood its ground and completed the project despite strong opposition. It was actually a very well-designed structure, created by Andreu, who also designed the Charles de Gaulle Airport, and I know him personally.

Given this precedent, the Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao administration continued the same approach. In other words, since we were pursuing reform and opening up, our architectural projects should be open to bidding on a global scale. And evaluators of the biddings shouldn’t be limited to only Chinese people either. Typically, only Chinese academicians were invited to serve on the evaluation committees, which is pretty awful. It’s like inviting top-level athletes and having the Chinese Football Association as the judges. That would be strange, right? So, it would have been only right that international evaluators should be involved.

Before the Bird’s Nest, another project was undertaken, which was the CCTV headquarters. The bidding for the CCTV building was also open to international applicants. At that time, a Swiss architect firm approached me through the Swiss ambassador in China, asking if they should participate in the bid because they totally lacked experience in China. Based on my own experience, I advised them not to participate because I believed that the selection process wouldn’t be fair and in the end, the decision would be made by political leaders, and sometimes they already knew who would be awarded the project even before the bidding had begun. It was because the various design institutes in China were tangled with complex relationships and political influences would play a decisive role. As a result, the Swiss firm I consulted didn’t participate. However, when the result came out, it was a surprise to everyone that the Dutchman Rem Koolhaas and his firm, OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture), won the bid. This indicated that the bidding and judging process went by the books, and a very innovative design was chosen. Later, the CCTV headquarters was criticized and mockingly called “big shorts” (大裤衩), but in reality, it was a very impressive project.

Why bring this up? Because coming up next was the international bidding for the main stadium of the Olympics. This time around, the Swiss firm didn’t come to me for advice. Instead, they asked me if I would be willing to join their design team to provide insights about China which they didn’t have. Additionally, they knew I was knowledgeable in contemporary art and I also spoke English, so that we could communicate easily with each other. I said yes because I was passionate about architecture at the time, and willing to get involved in pretty much any architectural project, be it a sports stadium or anything else — to me they were all architectural practices. At that time, my understanding of architecture was limited more to architectural design itself, not so much about everything else that was associated with it. It turns out that that’s what architecture is all about.

So I got involved in the design, and we won the bid. Needless to say, it was very exciting because we designed not only a national sports stadium, but also an audacious one. It was unprecedented, nor would there be one like it in the future, a project that was bold, ambitious, and hard to execute. But we won the bid.

Problems ensued. Dozens of academicians signed a joint statement claiming that China had become an experimental ground for foreign architects, wasting a lot of resources, like steel, on “colonialist” architecture, and so on. There was a horde of nonsensical criticisms, but no one spoke up for our winning project. As a participant, I voiced my opinions because others didn’t dare to or didn’t know how to express their views. I was forced into that position, and I couldn’t help but defend the architectural firm, because they themselves couldn’t step forward and speak up as they were the ones seeking funds and implementing the project and they couldn’t afford to offend anyone. But not me.

So once again, it intensified the confrontation between me and the real world. And profoundly so. This time I came into direct contact with decision-makers, academicians, and various layers of society, which turned me into a very socially active figure. I remember my younger brother Ai Dan (艾丹) advising me not to get too deeply involved in the world. Of course, he was trying to protect me, but I also felt that this was something I ought to do, so I did it.

For me, the Bird’s Nest project was my first involvement with the year 2008.

</p>

<p> ” data-medium-file=”https://i0.wp.com/chinachange.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ai-weiwei_wenchuan-earthquake_the-initium.jpg?fit=300%2C200&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i0.wp.com/chinachange.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ai-weiwei_wenchuan-earthquake_the-initium.jpg?fit=1024%2C683&ssl=1″ decoding=”async” loading=”lazy” width=”1024″ height=”683″ data-src=”https://cnmnewz.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/an-interview-with-ai-weiwei-part-one-the-year-2008-3.jpg” alt class=”wp-image-30884″ data-srcset=”https://cnmnewz.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/an-interview-with-ai-weiwei-part-one-the-year-2008-3.jpg 1024w, https://cnmnewz.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/an-interview-with-ai-weiwei-part-one-the-year-2008-17.jpg 300w, https://cnmnewz.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/an-interview-with-ai-weiwei-part-one-the-year-2008-18.jpg 768w, https://cnmnewz.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/an-interview-with-ai-weiwei-part-one-the-year-2008-19.jpg 120w, https://cnmnewz.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/an-interview-with-ai-weiwei-part-one-the-year-2008-20.jpg 1080w” sizes=”(max-width: 1000px) 100vw, 1000px” data-recalc-dims=”1″></a><figcaption class=) Collapsed school buildings in Wenchuan earthquake in 2008. Photo: The Initium.

Collapsed school buildings in Wenchuan earthquake in 2008. Photo: The Initium.But in 2008, two events also happened, both before the Olympics. At that time, I was already writing like mad, posting articles and giving hot takes every day. Suddenly, on May 12, the Wenchuan earthquake struck. I didn’t post anything on my blog for three or four days. My followers were all asking, usually you speak up about everything, but now that there’s a major earthquake, why are you silent? Everyone was wondering why I stopped writing.

The truth is, if I don’t know something, I can’t find words for it; if I can’t find the words, I can’t speak. I can’t just produce a bland voice. So I said I would go. So with my assistant Zhao Zhao (赵赵), I went to several sites in the disaster zone. We took some photos, and shot some videos. I felt the need to make a documentary, which eventually was completed with the title Little Girl’s Cheeks (《花脸巴儿》).

In addition to that, I wrote dozens of articles about the earthquake. The first article, as I recall, talked about the state’s rhetoric on how so many people were grateful for the government’s effective rescue efforts. I wrote that the government was supposed to carry out rescue efforts, and there was nothing whatsoever to do with gratitude. I wrote a lot of articles like that.

Then on July 1st there was the Yang Jia incident: a Beijing youth named Yang Jia (杨佳) stormed into a police building in Shanghai’s Zhabei district, stabbed six police officers to death, and injured several others.

Think about it, when an individual kills police officers, almost no one would bother defending his actions. But I started digging into the background of this event. Why did he do this? How did a young man from Beijing on a trip to Shanghai end up doing such a thing? I found that few people in China are willing to approach such incidents with a serious frame of mind.

But lawyer Liu Xiaoyuan (刘晓源) and I got into it. He did legal analysis, and I discussed it from a sociological or ethical standpoint. Who was Yang Jia? What led him to carry out this extreme act? Was he mentally ill? Did the police adhere to procedural justice in dealing with him? Or did the authorities simply want to eliminate him quickly? His defense lawyers were government-appointed, and they didn’t allow his family to meet him. The government disappeared his mother and committed her to a psychiatric hospital.

In the wake of the incident, I wrote at a feverish pace, churning out around fifty or sixty articles about the Yang Jia case. Lawyer Liu Xiaoyuan aside, who also wrote dozens of articles, I was the only layman willing to defend Yang Jia. The two of us worked hand in glove. But in the end Yang Jia was executed.

Then it was August 8, the opening day of the Olympics. By that time, I was overwhelmed with sorrow and frustration, and I didn’t attend the opening ceremony. My architectural team gave me a call as they sat in their VIP seats at the Bird’s Nest, saying, “Weiwei, we’re really sorry that you can’t be here.” They were all excited to be at the event.

I was at a bar in the neighborhood of Wangjing (望京), where I wrote an article on a piece of paper, which, to be precise, was the hospital report that my friend [Wang Fen] got that day – she was pregnant with Ai Lao, my son. That article can still be found somewhere. I wrote dozens of articles about the Olympics.

YC: I mentioned the phrase “two different worlds, two different dreams.” Everyone was saying, and you also mentioned in your book, that 2008 is year zero for China’s civil society.

AWW: I never brought up such a concept, and I completely disagree with this notion. There is no so-called civil society in China, nor are there so-called citizens. It’s a load of nonsense.

YC: In 2008, many volunteers and civil organizations sent aid to the earthquake zone and helped the victims. Don’t you feel that in that year, there was a kind of tension on display in China between civil society and the authorities in a particularly explicit and concentrated manner, revealing two different directions?

AWW: It doesn’t exist. This is all imagination of your kind. I believe that most people who weave such fantasies do so for their own personal purposes, in various forms. They are all petty rabble. These things have existed for a long time regardless of the era, but they have always been suppressed. They have always been there. It’s just that many people lack knowledge and cultural understanding of these activities, and information was not as developed. From before the Cultural Revolution, during the Cultural Revolution, and afterwards, these types of movements have always existed, including the April Fifth Movement [in 1976] and the Tiananmen Movement [in 1989]. They are so-called mass movements, somewhat group-oriented, but not really. These are loose activities. There was nothing special about the earthquake relief efforts in 2008 either. As I said, the government asked everyone to donate, people shed a few tears, and then jack all. Next, people began to express gratitude [towards the government], and that was basically it.

YC: For you personally, you mentioned two major events of 2008, one being the Bird’s Nest design, and another being your investigation into the tofu-dreg construction and their role in the deaths of thousands of students during the Sichuan earthquake…

AWW: No, not two but three events. For me, the Yang Jia incident is equally important as the design of the Bird’s Nest because it questions the fairness of China’s judiciary and social justice. This questioning is extremely difficult as most people immediately assume he is guilty because he killed six police officers. But how is guilt determined? How should sentencing be carried out? It is a serious matter. Similarly, the tax-evasion case against me in 2012 brought out the same issue, that is, as regards how social justice and procedural justice should be achieved. It concerns every individual and our way of life today. It’s even more important than my role in the design of the Bird’s Nest. But most people don’t understand it.

YC: That’s what drove you to pursue the Yang Jia case. What drove you to investigate the students deaths in the Sichuan earthquake, and what kind of ideas you worked into the design of the Bird’s Nest stadium?

AWW: Regarding the Yang Jia incident, as I mentioned, it is about how to achieve a very basic and primitive social justice. I discovered that there are countless loopholes and deficiencies in this society; society is really broken in almost every respect. Whether it’s the regime, policies, laws, public awareness, or the media, they are almost all as barren as a desert [when it comes to upholding justice]. But I am striving for it. Of course, as an individual, my voice was very weak, but regardless, I did write dozens of blog posts on the matter.

As for the Bird’s Nest, it’s actually quite simple. It is a building, a remarkable architectural achievement, but it was also used by the government as a propaganda piece. This actually is a moral failing on my part. I should have known that it was inevitable, but because I had a strong passion for architecture, I didn’t really think about it too much.

From an architectural perspective, it’s difficult for me to discuss the Bird’s Nest in technical terms because others wouldn’t understand it. So, I can only say that it is an extraordinary architectural achievement in the history of architecture.

Regarding the earthquake, it’s also quite simple. More than 70,000 people, around 70 to 80,000 people, died in the earthquake, and the government should bear responsibility for it. In China, nobody cared about farmers who died as their houses collapsed during the earthquake, because they built their own houses without government oversight and lacked the so-called inspections and approvals, so it was their own fault. However, what I questioned happened to be the shoddy construction of school buildings. Schools are built by the state, so if those buildings collapse, it’s indisputably the government’s responsibility. Some residential buildings or hospitals next to the schools remained intact, so why did the school buildings collapse? It must have been due to significant oversights in the construction process, such as substandard building materials. At that time, Premier Wen Jiabao (温家宝) solemnly pledged to investigate these tofu-dreg construction projects. However, in the end, the controversy was swept under the rug, and no one was held accountable.

So, the matter is quite simple as far as I was concerned: hold the government accountable, respect life, refuse to forget. That was our slogan at the time. Even though we called it a “citizen investigation,” it was a misnomer as there are no real citizens in China. It was just a few of us who made more than 40 trips to the earthquake zone and got arrested by the police many times. Some were beaten, others had their belongings confiscated, but we kept going there again and again. My assistants Xia Xing (夏星), Xu Ye, and others were all involved. That’s the short of it.

(To be continued…)

Related:

On April 24, 2010, Ai Weiwei (@aiww) started a Twitter campaign to commemorate students who perished in the Wenchuan earthquake in Sichuan on May 12, 2008, when sub-standard school buildings collapsed. 3,444 netizens delivered voice recordings, the names of 5,205 perished were recited 12,140 times. “Remembrance” is a three-hour audio work from these recordings, produced by Ai Weiwei Studio.

Comments are closed.