At the heart of the film ‘Oppenheimer’ is a clash between real-life Jews

In 1945 physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer was a national hero, hailed as the “father of the atomic bomb” and the man who ended World War II.

Less than a decade later, he was a pariah, after the United States Atomic Energy Commission revoked his security clearance following allegations about his left-leaning politics at the height of the anti-communist McCarthy era.

Christopher Nolan’s biopic, “Oppenheimer,” which opens in theaters on July 21, will star Irish actor Cillian Murphy as the famous scientist. But it will also feature Robert Downey Jr. as a lesser known real-life character, Lewis Strauss (pronounced “Straws”), the chairman of the AEC and one of Oppenheimer’s chief inquisitors.

The clash over the nuclear bomb

The clash between the scientist and the bureaucrat was a matter of personalities, politics and the hydrogen bomb (Strauss supported it, Oppenheimer was opposed). But according to amateur historian Jack Shlachter, the two represented opposites in another important way: as Jews. Shlachter has researched how Oppenheimer’s assimilated Jewish background and Strauss’ strong attachment to Jewish affairs set them up for conflict as men who represented two very different reactions to the pressures of acculturation and prejudice in the mid-20th century.

Shlachter is in a unique position to explore the Jewish backstory of Oppenheimer: A physicist, he worked for more than 30 years at Los Alamos National Laboratory, the New Mexico complex where Oppenheimer led the Manhattan Project that developed the bomb. Shlachter is also a rabbi, ordained in 1995, who leads HaMakom, a congregation in Santa Fe, New Mexico, as well as the Los Alamos Jewish Center.

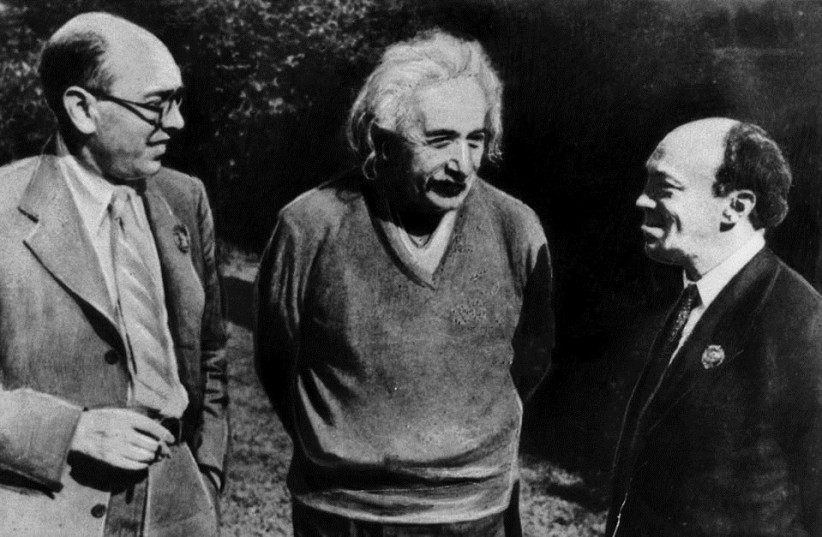

Albert Einstein (Middle) is seen standing between Yiddish poet Itzik Feffer and Russian Jewish actor Solomon Mikhoels in 1943. Feffer would be killed in the Night of the Murdered Poets, while Mikhoels was killed in what may have been an assassination ordered by Joseph Stalin. (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Albert Einstein (Middle) is seen standing between Yiddish poet Itzik Feffer and Russian Jewish actor Solomon Mikhoels in 1943. Feffer would be killed in the Night of the Murdered Poets, while Mikhoels was killed in what may have been an assassination ordered by Joseph Stalin. (credit: Wikimedia Commons)“A hero of American science, [Oppenheimer] lived out his life a broken man and died in 1967 at the age of 62,” The New York Times wrote last December, after the secretary of energy nullified the 1954 decision to revoke Oppenheimer’s security clearance. Lewis Strauss died in 1974 at age 77; his funeral was held at New York’s Congregation Emanu-El, where he had been president from 1938 to 1948.

When I asked Shlachter what drew him to the story of Oppenheimer and Strauss, he told me, “At this later stage of my life, I realized that things are not black and white. The common narrative that I think I have heard in town puts Oppenheimer at 100 and Strauss at zero. I just tried to balance that a little bit, and I thought that their Jewishness was one way to see that there’s some nuance in the relationship.”

Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

There has been a lot of talk about Oppenheimer in anticipation of the Christopher Nolan film, but I haven’t seen much on his Jewish background. I guess as a rabbi and a physicist at Los Alamos this was a subject you couldn’t resist.

I am speaking as a private citizen, not on behalf of Los Alamos National Laboratory or anything like that. Oppenheimer was the first director of what is now Los Alamos National Laboratory. He was the scientific leader of the Manhattan Project. And it was really his doing that the laboratory ended up in northern New Mexico. He has been out here as a late teen and really fell in love with the desert Southwest.

His Jewishness is a bit complicated. His father was an immigrant from Germany in the late 1800s. And his mother was a first-generation American but her parents had emigrated to the United States. And in their approach to religion, they became enamored with the Ethical Culture Society of Felix Adler.

That’s the non-sectarian movement that had roots in Reform Judaism and is based on the idea that morality does not need to be grounded in religious or philosophical dogma.

Correct. Samuel Adler, Felix’s father, was brought over from Germany to serve as the rabbi of New York’s Temple Emanu-El, then and now a major Reform synagogue. They sent Felix back to Germany to study and he got his PhD in Heidelberg, and the plan had been for Felix Adler to succeed his father at some point. He came back in his 20s and gave what was his first and last sermon at Temple Emanu-El. He had adopted and absorbed some ideas while he was in Germany that were completely anathema to the Reform community, and he spun off the Ethical Culture Society.

Julius Oppenheimer, Robert’s father, was a trustee of the Ethical Culture Society, and Felix Adler conducted the wedding ceremony of Julius to Ella Oppenheimer, Robert’s mother. J. Robert Oppenheimer was educated at the Ethical Culture school. It was supposed to be non-religious and yet it was clearly dominated by Jews. It was one of these things about being American through and through, and somehow not having Judaism stand in the way. I think that really shaped Oppenheimer’s approach to Judaism.

Was there an ethos that he might have absorbed from the Ethical Cultural school that would have been important either in his left-wing politics or in his approach to the Manhattan Project?

My suspicion is yes, because Felix Adler in his training in Germany had become quite interested in Karl Marx and in the plight of the working class, and it seems impossible to me that that didn’t get somehow transmitted at the Ethical Culture school. It does not surprise me that Oppenheimer’s politics were left leaning.

As an adult, did Oppenheimer ever talk about his Judaism publicly or explain what his connection was to either the people or the faith?

Almost not at all, although there are some quite interesting quotes from other people. The Nobel laureate physicist Isidor Isaac Rabi and Oppenheimer were quite close, and Rabi testified on Oppenheimer’s behalf at the security hearing in 1954. According to Ray Monk’s massive biography of Oppenheimer, Rabb says that “what prevented Oppenheimer from being fully integrated was his denial of a centrally important part of himself: his Jewishness.” And Felix Bloch, who was another Jewish physicist who went on to win the Nobel Prize, said that Oppenheimer tried to act as if he were not a Jew, and succeeded because he was a good actor. You know, when you can’t integrate yourself and you’re trying to distance yourself from your roots, you can become conflicted. That’s Rabi’s assessment of Oppenheimer’s connection to Judaism.

But you also found a few instances of Oppenheimer positively engaging with Jews and Judaism.

In 1934, when Oppenheimer was a professor at Berkeley, he earmarked 3% of his salary for two years to help Jewish scientists emigrate from Germany. I think the fact that they were scientists was the important thing, and of course they were Jewish, because they’re the ones who were trying to get out in 1934. I don’t know that he was doing this because they were Jews or because they were scientists. Supposedly, Oppenheimer sponsored his aunt and cousin to emigrate from Germany, and then he continued to assist them after they came to the United States.

And then in 1954, at the security clearance hearing, Oppenheimer said that starting in late 1936, he developed “a continuing, smoldering fury about the treatment of Jews in Germany.” I don’t know if you had gone back to 1936 that you would have found any evidence of him saying that at the time. I doubt it. But one thing to remember is that in Oppenheimer’s lifetime, antisemitism was not non-existent. Antisemitism shaped how people dealt with their Judaism and this was the way he dealt with it.

So fast forward, Oppenheimer grew up well-to-do in New York and was educated at Harvard and then in Europe, where he studied physics at the University of Cambridge and the University of Göttingen. He joins the staff at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory at Berkeley, and he begins socializing with leftist professors — both communists and so-called fellow travelers, deeply involved in workers’ rights and supporting the anti-fascists in the Spanish Civil War — in ways that are going to come back to haunt him in the 1950s. In the “American Prometheus” biography, which Nolan’s film is based on, we learn that Oppenheimer’s political activities came to the attention of the FBI at this point, years before his work on the atom bomb project.

That’s correct. He clearly had sympathy for those causes. And I would say understandably. There was a depression going on in this country, and the workers’ condition was not perfect.

There are now historians who are claiming Oppenheimer really was a card-carrying communist despite his denials. He certainly was a fellow traveler, his brother Frank was clearly a card-carrying communist as was Robert’s future wife Kitty.

In 1942 Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Grove was appointed director of what became known as the Manhattan Project, and selected Oppenheimer to head the project’s secret weapons laboratory.

Groves and Oppenheimer seem to have a chemistry which was critical for the success of the project. Why Groves figured that Oppenheimer was the guy to lead it is a little bit of a mystery. Oppenheimer had not led anything even remotely like this. He was a theoretical physicist, and you’re talking about huge experimental facilities for the project. And he wasn’t yet 40. But Oppenheimer rose to the occasion.

You mentioned earlier what Oppenheimer later described as his “smoldering fury” over the Nazis treatment of the Jews. Did working on a bomb to defeat Nazi Germany assuage whatever pangs of conscience he might have had over developing a bomb of such massive destructive potential?

I do think so. And that was probably true for many of the scientists who worked on the project, many of whom were Jewish. There was also a suspicion that the Nazis were working on a bomb as well and then God forbid that they should get there first. I think that was really the driver.

I’vre read that Oppenheimer did not feel guilt over his contribution to developing nuclear weapons or the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki but he did feel a sense of responsibility for what had been unleashed.

Oppenheimer realized that a lot of people lost their lives as a result of this. But I will tell you, my father was a GI during World War II, he enlisted in 1943 and fought until ’45. He was in Europe when V.E. Day came, and then came back to the United States for leave before he was going to be shipped out to the Pacific. And my father was convinced to his dying day that the bomb saved his life [by ending the war with Japan]. And, you know, that was a widespread sentiment.

After the war, Oppenheimer ends up in Princeton directing the famous Institute for Advanced Study and that’s going to bring him into the crosshairs of Lewis Strauss. Tell us who he is and how these two Jewish figures contrasted.

Three of Strauss’ four grandparents emigrated from Germany/Austria, probably in the 1830s, 1840s. Somebody ended up in Virginia and Strauss grew up in the South. His connection to Judaism is quite different from Oppenheimer’s. Strauss was a valedictorian of his high school and in his autobiography says that he was absolutely fascinated by physics. But the family had no money so rather than go to college Strauss became a traveling shoe salesman. And even though merchants he sold to would be closed on Sunday, he insisted on [also] taking Saturday off because of his Judaism, and he took the financial hit. He ended up volunteering to work for Herbert Hoover, the future Republican president, who was organizing European relief efforts after World War I. Hoover becomes a lifelong friend, advocate and supporter. Strauss managed to push Hoover — no friend to the Jews — to lodge a formal complaint when some Jews were slaughtered by the Poles.

He had a pretty meteoric rise. He gets connected to the Kuhn, Loeb investment firm, marries the daughter of one of the partners and he makes money hand over fist. But he stayed connected with his Judaism through all this, eventually becoming the president of Temple Emanu-El for 10 years from 1938 to 1948. So just like there are political differences between Oppenheimer and Strauss, there are religious differences: Oppenheimer grows up in the Felix Adler breakaway and Strauss is mainstream Reform Judaism.

Strauss was a trustee of the Institute for Advanced Studies when it hired Oppenheimer. What else came between the two men? I’ve read that Strauss was a proponent of the hydrogen bomb, and Robert Oppenheimer was hesitant because he felt the astronomically greater power of the H-bomb was not necessary.

The H-bomb was physicist Edward Teller’s idea — he called it “the super” — and Oppenheimer appropriately sidelined Teller at Los Alamos, saying “this is a distraction from what we’re trying to accomplish.”

The animosity between Strauss and Oppenheimer had probably several different dimensions. But I think Strauss also had to navigate being Jewish in an American society that didn’t totally embrace Jews, and I think it was somewhat of a threat to him to have somebody like Oppenheimer whose approach to dealing with his Judaism was to hide it, basically. Here’s Strauss, you know, president of Temple Emanu-El, he’s clearly not hiding that he’s Jewish, and he’s trying to survive and thrive in a Washington establishment that’s not so embracing of Judaism. So that was another dimension. I’d even read that Strauss was offended by Oppenheimer’s alleged marital infidelity.

The animosity also includes the fact that Oppenheimer could be mean. Generally, people who worked at the laboratory loved him, but he could also be mean, and he made Strauss feel like a fool in a public hearing in 1949 — sort of like, “You’re an amateur physicist. You don’t know what you’re talking about,” and that really cut to the quick.

Whatever the reason, Strauss is not a good enemy to have when he becomes a trustee of the Atomic Energy Commission. It’s Strauss who in 1953 told Oppenheimer that his security clearance had been suspended, and led Oppenheimer to request the hearing that led to his security clearance being revoked.

Strauss was appointed one of the five members of the original Atomic Energy Commission. The chair at the time was David Lilienthal, also Jewish by the way, and there’s a photograph of the five members of the Commission that’s absolutely perfect because there are four people on one side on the left, and one person sort of off by himself on the right — and it’s Strauss who’s off by himself. And there were apparently a few dozen votes of the Commission in its early years, mostly having to do with security matters, where the vote was four to one and Strauss was the lone dissenting voice. He was focused on security and was probably very anti-communist.

I want to shift gears and talk about your background, and how a physicist becomes a rabbi.

I was a graduate student at the University of California, San Diego, and my thesis advisor sent me to Los Alamos for the summer of 1979 to learn a certain piece of physics. My connection to Judaism at that stage in my life was almost nil. I had done the classic sort of Conservative American Jewish upbringing of post-bar mitzvah alienation. When I came to Los Alamos I didn’t know a single person in town, so I thought I could go to the synagogue and meet some people. And because my training was reasonably thorough in the liturgy, I started leading some things at the synagogue while I was here.

Instead of going back to UC San Diego, I ended up continuing my graduate studies at the laboratory and completing my PhD while I was still here, and then got hired as a staff member at the laboratory. And all that time there was a rabbi who was coming up from Santa Fe to Los Alamos, and would teach an adult education class and I got interested. I had the arrogance of a newly minted PhD physicist that if you can learn physics, you can learn anything. So I started doing a lot of self-teaching in Judaism.

And what I discovered, which is my passion in the rabbinate, is that adult Judaism is not taught to kids because kids are kids. And most people reject Judaism like I did because they don’t know that Judaism is much richer than what most people reject. I spent my entire physics career here at the lab and in parallel, as I became more knowledgeable in Judaism, I came to know that I didn’t know anything. Then it turns out that there was a rabbi, Gershon Winkler, who moved to New Mexico and took me on as a private student, and that process led to my private ordination through him.

To pull the threads together, I’m curious how you as a physicist think about your responsibility for the uses of science, and how they mesh or clash with what you are learning in Torah.

I’ll steer your question slightly, if that’s okay. [The medieval Jewish philosopher] Maimonides says clearly that we’re given brains and the ability to do rational thought. Judaism is, it seems to me, inherently compatible with the idea of using your brain to understand how the world works, which is what physics is all about. Physics can help us see the beauty in the universe. And that beauty is part of what we’re given as a responsibility to appreciate in Judaism as well.

But science can also be applied for destructive purposes.

We are in a world that is not perfect. And, you know, there have been wars since time immemorial. Atomic weapons were used to end a war, and that was important. Like I said, my father to his dying day felt that his life was saved because of the atomic bomb, and you know, who’s to say that he was wrong?

In Los Alamos, how does the community process their legacy? Is it one of unmitigated pride or is it always leavened by regret about the destructive forces that were unleashed?

I think Oppenheimer is generally viewed very positively. What happened in Los Alamos was an important part of the history of the world. And it’s inspiring to be here at a place where, 80 years ago, there was basically nothing but a small boys’ school.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of JTA or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.

Comments are closed.