Combat Always Makes Fast Friends—Uncovering the Story of a Trailblazing Woman War Correspondent

The following is an excerpt from First to the Front: The Untold Story of Dickey Chapelle, Trailblazing Female War Correspondent by Lorissa Rinehart. From the beginning of World War II through the early days of Vietnam, photojournalist Chapelle chased dangerous assignments her male colleagues wouldn’t touch but was still forced to overcome discrimination both on the battlefield and at home, with much of her work ultimately buried from the public eye. Dickey faked her own kidnapping, jumped out of planes, and marched with fighting forces on four continents to document history-making events. She was the first American female journalist killed while covering combat.

The chopper dropped off Dickey Chapelle in mid-October. A squadron welcomed her on the landing pad, firing a 21-gun salute and raising their flag. Dickey quickly fell into the village’s rhythm.

Every morning, bugles called the village to wake, soldiers to drill, and prisoners to work. Ducks and pigs and dogs and babies composed the chorus of afternoons. Stringed pipas—instruments similar to guitars—and mouth harps announced the end of the workday. Sometimes, when the air was cool enough, the militia’s radio picked up the Saigon jazz station that was piped through an enormous Pioneer loudspeaker, washing the village in Coleman and Coltrane, Evans and Getz, Mingus and Roach. The resounding percussion of tanggu drums called the devout to evening prayers at the Our Lady of Victory Chapel. In the dark, gongs made from flattened mortar-shell tips rang out the all-clear every hour on the 45, except when incoming Viet Cong bullets made them chime like kindergarten triangles. This music played almost every night. The Sea Swallows replied with their own refrain of artillery, mostly left over from the French Indochina War, along with psyops messages broadcast over the same loudspeaker that earlier might have played jazz.

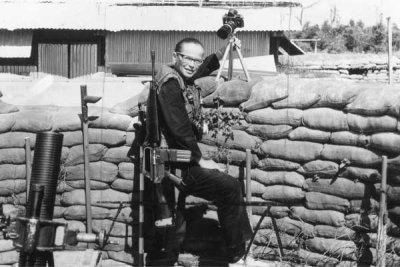

Though the Geneva Conventions prohibited journalists from carrying firearms, Dickey believed the realities of the Vietnam War required that journalists be able to defend themselves—as well as help the battalions they were embedded with—if the need arose. Here, Dickey is pictured carrying a semi-automatic rifle while embedded on the Vietnam-Cambodia border with the South Vietnamese Marines. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

But more than defend, the Sea Swallows went on the offensive against the Viet Cong and had so far secured a five-mile perimeter around the village. Dickey, of course, insisted that she accompany them. The night before her first patrol, she joined the officers for dinner in their mess beside the Sea Swallows’ armory. On one side of the long table, two German shepherds—gifts from U.S. Army Research and Development—strained at their leashes. On the other, soldiers tossed their scraps to caged boa constrictors. Dickey sat in the center beside the ranking officer, Capt. Nguyen, who talked of the liberation of Vietnam while Dickey used chopsticks to feed succulent crab to the cat that had crawled onto her lap. Occasionally, a soldier would interrupt, asking the captain to inspect his modifications on a 1953 French mortar or World War I bullets that had been polished back into working order. Each time, he nodded a hesitant approval. They needed new weapons, but these would have to do. After dinner, Nguyen handed Dickey a carbine to carry the next day.

“You might need it,” he cautioned.

Dickey went back to her quarters to practice carrying the gun along with her cameras.

“How do Marine combat correspondents do it with an M-1?” she wrote in her journal, then packed her pockets with extra film and cigarettes for the next day’s march.

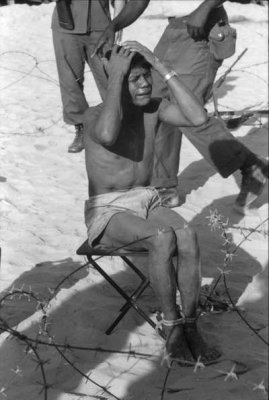

Having been a prisoner of war herself, Dickey was often outraged by the treatment of suspected Viet Cong combatants. In her mind, the abuse of an individual’s human rights and civil liberties, such as those she documented here, could not and would not win the war. Photo by Dickey Chapelle, courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

They left during a thick rain at dawn, made too much noise, and only had a captured flag to show for their mosquito bites.

“I scratched like a civilian,” Dickey wrote.

Still, the squadron gave her the flag. She would later unfurl this keepsake from her purse on stages in the Plains states to drive home the necessity of supporting the Sea Swallows and groups like them.

That afternoon she photographed the demolition class in the chapel. Like her, the instructor was an outsider, a member of the Vietnamese special forces sent here both to teach and to learn. She had met him before, what seemed like a lifetime ago, on one of her first patrols in the highlands.

“Don’t you get homesick?” he asked her as his students practiced inserting fuses. Then shyly added, “I think you are willing to die for your duty.”

“I’m sure you are too,” she replied, “We might both live through our whole careers.”

The look on his face told her she had said the wrong thing. He expected to die defending the freedom of his country. To think otherwise was tantamount to a dereliction of duty.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

A week later, Nguyen announced the next patrol mission beyond the walls of Binh Hung, South Vietnam. The troops assembled in a portentous gray dawn. Dickey ignored the omen, instead scanning the faces of the hundred assembled regulars as Nguyen gave them their orders.

“I was surprised to realize how many of the Binh Hung faces had become familiar and even a little dear to me in the 10 days I have been among them,” Dickey wrote in an unpublished article about the operation. But combat, she knew, always made fast friends.

Nguyen dismissed the men to load into the Sea Swallows’ fleet of weathered motorboats with mounted automatic rifles at the bow and stern. Amidships, soldiers clutched their American M1s and French Lebels with shells in the chambers and their safeties off. Bathing children laughingly swam out of their way as the boats departed down the canal. Dickey noted with no small degree of sentimentality the woman who saluted the soldiers, then blew a kiss to her husband behind his Browning automatic.

Though adamantly against the abuse of prisoners of war, Dickey had no sympathy for the NLF and their North Vietnamese allies, the Viet Cong, having seen all too often the aftermath of their attacks. Here, Dickey captures the fear and uncertainty of the inhabitants of Vinh Quoi whose homes were destroyed by an NLF raid. Photo by Dickey Chapelle, courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Outside the village, water lilies and floating buttercups swirled in the eddies of the Sea Swallows’ wake. Skirting the edge, farmers on the way to market poled their sampans stacked high with bundles of watercress, bananas still on the stalk, baskets full of fish, and clinking bottles of home-brewed beer. On the banks, children played and fishermen fished, boatbuilders caulked their hulls, and housebuilders thatched a new roof. The whole scene seemed so utterly pastoral, so opposed to their actual purpose.

A stone lion and live Tommy gunners guarded a Buddhist temple just outside Tan Hung Tay, where the Sea Swallows rendezvoused with a company of Montagnard militia.

“They are mountain people from central Vietnam,” wrote Dickey, “the Father and the captain have been delighted with their performance. … My first chore of the day was to help prove it by photographing a Viet Cong corpse lying in the marketplace.”

She then added parenthetically, “I guess I should point out that in my experience, the public exhibition of enemy dead is still considered a pretty normal part of warfare in every culture but our own.” Inured by now to the spectacle of violence, the marketgoers hardly noticed the body as they went about their shopping. With equal nonchalance, Dickey focused her lens on metal spikes across his chest, classic Viet Cong booby traps that he had been caught planting along the path into town.

Dickey spent several days on Okinawa during the initial push to overtake the island. Here, she captures a military truck driving past three Okinawan women and a small child, who picnic in the grass. Photo by Dickey Chapelle, courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Reports of an approaching enemy column took them farther down the canal to Van Binh, another Catholic Chinese refugee settlement where the Viet Cong had recently poisoned the drinking water and shelled the market. The village chief welcomed the Sea Swallows with a feast of pork liver soup, roast duckling, shrimp, crab, beer, and French brandy. Evening fell. Dickey slept in the same barracks as the soldiers and woke with them before dawn.

“The first firing came at 08:10 exactly,” Dickey wrote, “a few rifle shots and a submachine burst of three. Then for several minutes, the fire was so heavy that I couldn’t count.”

Dickey expended a roll of film and was loading another when she saw the mortar crew run by. She followed, film in hand, and dropped to one knee as the crew assembled the mortar in three and a half minutes flat. They fired. A dud. Military protocol dictated waiting 10 minutes before loading a new shell in case the old one had simply yet to explode. But there was no time for such caution under heavy fire closing in on a thousand yards. Without hesitation, the crew reloaded and fired three more times. On the fourth, incoming fire slackened and the enemy dispersed.

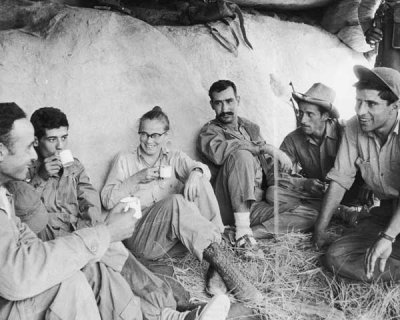

Dickey’s familiarity with military training made her comfortable with soldiers the world over, and likewise they with her. Here, she shares a cup of Turkish coffee with members of the FLN Scorpion Battalion. Photo by Dickey Chapelle, courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Whatever misgivings the Sea Swallows or any citizens of Binh Hung had about Dickey disappeared after that. Farmers’ wives hosted dinners for her. The commander of Companies Six and Seven invited her to his wedding. She celebrated the Vietnamese Independence Day by setting off fireworks with the best of them, went to children’s birthday parties, and attended mass on Sunday. And, whenever the Sea Swallows went on maneuvers, she went with them.

She regularly joined them on perimeter night patrols and marched out to confront reported bands of Viet Cong. She came under fire nine times, endured clouds of mosquitoes so thick they clouded her glasses, and watched deadly snakes slither by her boots as she stood motionless for fear the smallest sound might alert the enemy to their location.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

She described in gripping detail the dangers and difficulties of warfare in Vietnam that confronted the Sea Swallows even before one reached the enemy—charging water buffalo, mined canals and spiked foxholes, and terrain that both the Viet Cong and Military Assistance Advisory Group personnel considered equally impossible to traverse but which the Sea Swallows crossed by the mile. She portrayed them as they were under fire, cool and collected as any soldiers she’d ever seen.

This War Horse book excerpt was reported by Lorissa Rinehart, edited by Kelly Kennedy, reviewed by St. Martin’s Press, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Headlines are by Abbie Bennett.

Comments are closed.