Get Ready For America’s Next Great Solar Eclipses

Six years ago, residents and visitors across the United States witnessed a solar eclipse moving eastward across the sky. Now we’re due for an encore over the next eight months — actually, two of them.

The first recurrence will be an annular eclipse on Saturday, Oct. 14 later this year. The second — like its 2017 predecessor — will be a total eclipse on Holy Saturday, April 8 of next year.

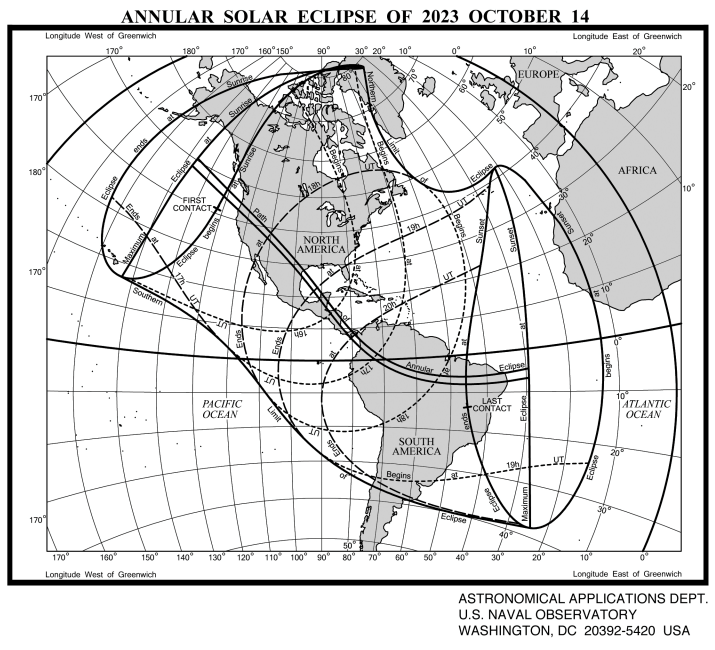

The 2017 eclipse traversed across our continent from Oregon to South Carolina. This year’s eclipse also reaches landfall in Oregon and travels southeast toward Texas before proceeding over Central and South America.

U.S. Gov’t, public domain

The 2023 path predominates the western portion of the United States, as shown by the U.S. Naval Observatory. A lovely interactive color map is also available from Xavier Jubier.

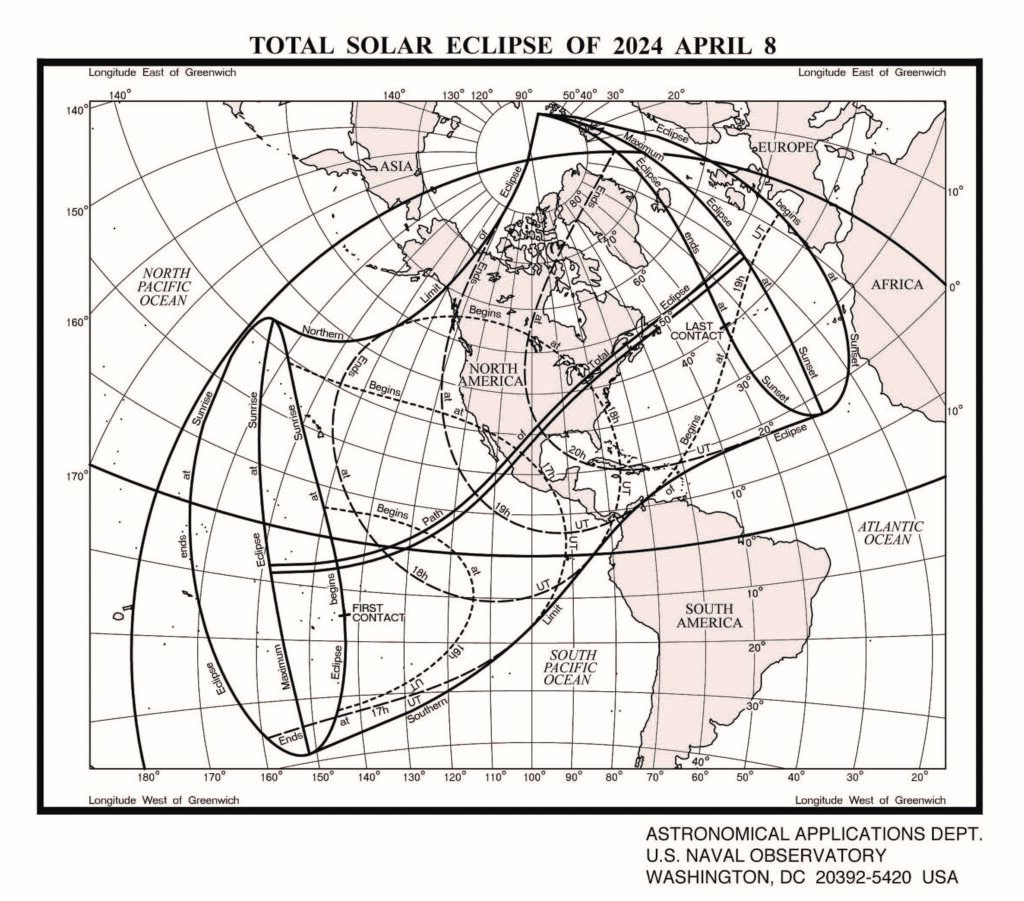

Next year’s eclipse will darken the sky from northwestern Mexico, enter Texas from the Rio Grande, and leave Maine, finally ending its North American visit through eastern Canada. The paths of the 2017 and 2023 eclipses intersect off the Oregon coast, while those of 2017 and 2024 cross between the southern border of Missouri and Illinois. The paths for the upcoming eclipses will coincide in southern Texas.

U.S. Gov’t, public domain

The 2024 path predominates along the eastern portion of North America, as shown by the U.S. Naval Observatory. Here’s a lovely interactive color map.

Among the planets of our solar system, Earth is unique in having a moon that looks comparable to the size of the sun from our planet’s surface because of the area and distance ratios. This fortuitous arrangement permits the moon to completely obscure the sun while allowing the sun’s atmosphere — normally too bright to see with the unaided eye — to become visually prominent. For the second and third time in seven years, vast portions of the United States will witness the moon blocking the sun.

What You Can See

The moon’s orbit is slightly elliptical, with Earth at one node. The moon presents a slightly larger disk from Earth’s surface when closer than when farther away. This difference determines whether the lunar face completely obscures the sun’s photosphere.

October’s annular eclipse will leave a sliver ring of the sun peeking through. By contrast, next April’s total eclipse — like that from six years ago — will entirely cover the sun, enabling viewers to see the sun’s corona, which is otherwise too bright to see.

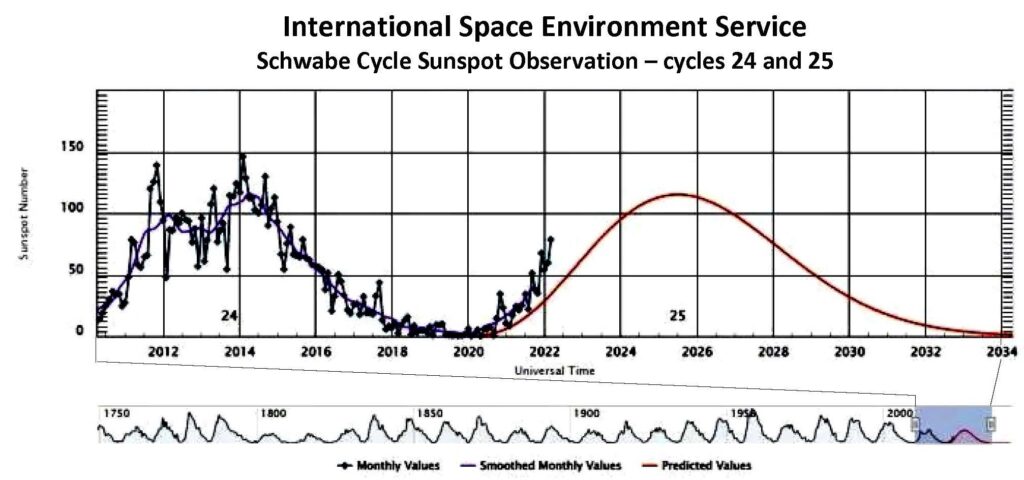

But there’s a twist: April’s corona is expected to be more symmetrical and expansive than in America’s prior event. The sun’s magnetic poles reverse approximately every 11 years, which corresponds to an increase in sunspots and magnetic flares.

Sunspot activity is anticipated to peak in early 2025. By contrast, 2017 lay within the interim period approaching the sunspot minimum.

With increased sunspot activity, April’s event may more closely resemble the Saturday, Feb. 16, 1980 eclipse over the Democratic Republic of the Congo (now Zaire), Tanzania, Kenya, and India.

Solar Behavior

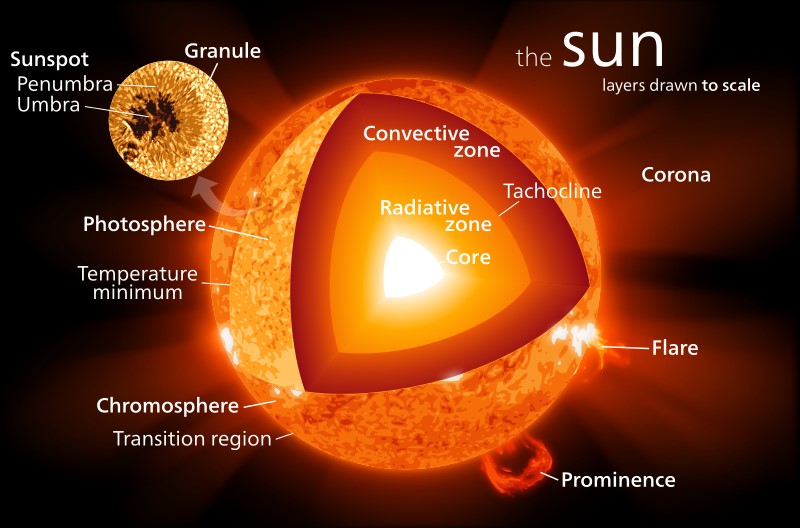

These and other solar cycles result from particular properties inherent in astrophysics. The sun’s energy originates at its nuclear core, where hydrogen nuclei fuse into helium.

A radiation envelope of hydrogen and helium ions surrounds this small core (about a quarter of the surface radius). A convection mantle further covers this zone with the photosphere revealing the visible layer, further surrounded by the chromosphere and corona.

As a glimpse of the peculiar nature of our closest star, the sun’s average density (mass-per-volume) compares to polyvinyl chloride (the plastic used for plumbing), while Earth’s average density is that of tin. However, the density of the sun’s core is 13 times that of lead — indicating the enormous pressure from the sun’s mass toward the center.

You and I and everything that surrounds us on our planet are composed of cold matter that radiates energy in the infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. By contrast, stars are comprised of compressed plasma: atomic nuclei along with unbound electrons all too hot to combine to form atoms. The illustration below shows these solar zones.

At each stage in the sun’s interior, the photons’ peak energy attenuates from gamma rays released from the core to visible light emitted in the photosphere. Without these intermittent layers to ameliorate the sun’s energy, we would literally be baked to a crisp. The solar wind also radiates high-energy particles, but Earth’s magnetic field deflects these effects.

Because the convection mantle is not rigid, the sun’s equator rotates angularly faster than its poles, causing internal shear strain. This solar dynamism yields irregular electromagnetic flares from the surface, along with internal turbulence to switch the magnetic poles. Sometimes these flares escape beyond the sun in a phenomenon called coronal mass ejections, one of which electrified telegraph wires in September 1859.

What’s an Orbital Rhythm?

Why do solar eclipses seem so occasional? Technically, the moon’s shadow on the Earth occurs more frequently than Earth’s shadow on the moon, as Jared Owen briefly animates. Yet far more people witness lunar eclipses than solar ones.

This is due to the former being visible throughout the entire nighttime sky, whereas the moon’s blockage follows a narrow trace that is only a few dozen miles. These courses also usually occur over uninhabited regions such as oceans and deserts.

Make Sure to Protect Your Eyes

NASA cautions viewers to avoid looking at the eclipse directly except at totality (when only the corona is visible), as the sun’s near-infrared and ultraviolet radiation can damage the retina without our realization. To avoid eye damage, one can purchase certified eclipse eye shades as filters to safely enjoy such an uncommon and awesome event.

If you miss both of these eclipses, you’ll have to wait until Saturday, Aug. 12, 2045, for the next sweeping affair (unless you go overseas).

Solar eclipses hold a special place in our consciences — perhaps due to their beauty and comparative rarity. The 2024 event will pass over a more densely populated portion of the United States than either the 2017 or 2023 eclipses, so it should be reachable for the most viewers. Make sure to mark your calendars!

G. W. Thielman has bachelor’s and master’s degrees in engineering. He is currently employed as a patent attorney, and lives in Fredericksburg, Virginia. His opinions are his own.

Comments are closed.