This Is the Crucible That Forged Me, But I Am No Piece of Steel. None of Us Are.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, consider the power of our memories that linger like hazy images until they are resurrected by the smell of burned rubber or bug spray, the nostalgic power of a song, or the sound of helicopters passing overhead. Our senses open the door to grief, joy, guilt, and pain. These are the snapshots that make up my story and memorialize the cost of resiliency.

Got a new bike. I stomped my coaster brakes to lay a streak of burnt rubber on a new patch of sidewalk near Sunnyside Elementary School, but my brakes weren’t there. My new freewheel sprocket spun bear trap pedals into my shins with a vicious impact that I felt in my soul.

I was tough; I kept riding.

That summer I got a call from Dad. He was out of prison. I was playing in the yard and raced in, sweating and out of breath, with the musty outside smell in my hair and mosquito bites on my bruised shins, but I knew what he was gonna say before I heard his gravelly voice.

“Not gonna make it again, Skeeter. Got another load to pick up in Dallas. Wanted to call to say happy birthday. I’m sorry, son.”

I felt that in my soul too, but I’d heard it before.

I’m tough; I keep playing.

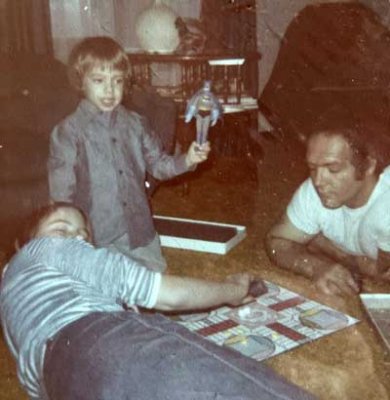

Lance Minor and his sister on Christmas morning 1977 with their new stepdad, Jack. Photo courtesy of the author.

Got a new dad the next May. His name was Jack. I can still smell the new denim shirt and the rubber of my Batman action figure. We played Sorry and Parcheezee on a Christmas so great Mom broke out the flash cubes for the Kodak. Glad we have the pictures because things don’t last—at least not Dads.

I knew something was wrong when that strange feeling came to me. I raced home from Ms. Guerro’s kindergarten class, across fresh-cut lawns to tears and to hear about a car crash and jaws of life that weren’t strong enough to pull us away from the loss.

That was the first time my soul broke. I hid in my mom’s closet, surrounded by fur coats, polyester, and white patent leather, until I wasn’t afraid of the dark anymore, until I was tough again.

I embrace the darkness now.

Stood on the yellow footprints in ’91.

The Few, the Proud spoke to me on Saturday mornings, between Jonny Quest, the Justice League, and the Transformers. Over bowls of Froot Loops, those men looked like real heroes, so when the time came, I raised my hand.

At 18, I had my own baby to take care of, though I was still a boy myself when I arrived at the depot, dreaming of the freedom I gave up. The airport was right there, across the physical training field. Motley Crue’s “Home Sweet Home” wormed into our ears and we longed to be on one of those planes.

“Pain is weakness leaving the body,” they say, so I stayed; I needed to change and grow to be tougher for her.

So I submitted, sweated, swore, and swore to be more than they were. More than a drunk trucker and dead Jack.

I am.

I claimed more than the title Marine that day. Semper Fidelis, but am I?

I was a scout swimmer in 3/8ʼs boat company, dropped off in the ocean, far over the horizon. The Zodiac motored away, leaving us alone with the moon and the mission to reconnoiter an unknown beachhead.

Lance Minor as a young Marine. “Resiliency is more than pushing on when you’re tired,” he writes. “It’s understanding what you’ve learned—and growing stronger from it.”

Phosphorescent plankton washed over my wetsuit with the pulsing waves as I hunched over to attach my fins. I felt the pop. My heart dropped. The moon and plankton were just bright enough for me to watch my right fin sink into the depths, into the darkness.

The mission was at stake, I had to go on.

I made the swim with one fin, dolphin-kicking the entire way. There was no going back, no safety boat, no life preserver.

“Dummy cord everything,” they say, but I didn’t that time. I was the dummy that day. That was a lesson in surrendering, accepting one’s vulnerability and stupidity, but succeeding nonetheless.

Bailed my buddy Duke out of a bar fight in ’94.

I was the sober one but threw the only punch, and the O’House erupted with Copenhagen and blood, stale beer, and adrenaline, but I made enough room to push Duke out the door right into a cop.

“Thank God! There’s a guy in there with a broken bottle and he’s pissed off!” I said, hoping he wouldn’t notice the bloody knuckle or my trembling hands. He didn’t, but the knuckle got infected, and I ended up in a hospital bed the next day when I got a call from my mom with an update on the Trucker; I knew what she was gonna say as soon as I heard her weary words.

“I’m sorry, Son, but your dad killed himself last night. They found him in the bathtub in a motel in Pratt, Kansas.” I wondered if I was on his mind at all.

My mind conjured the smell of Old Spice mixed with copper, piss, and bourbon as I imagined him slashing the razor across his elbows, not his wrists, in a final act of self-loathing and loss. Probably not.

My soul was too numb to feel broken, so they transferred me from 3/8 to 2/8. I missed our med float, but I miss my father more, even though he was never really there.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

This time, there was no closet to hide in, just questions to ponder. On my darkest days, I’m stronger because I never want my daughters to feel this way.

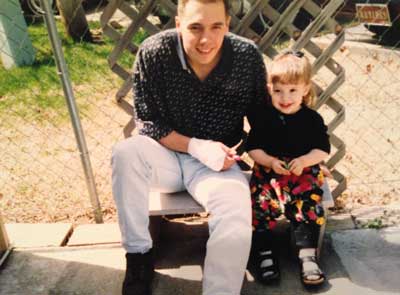

As a father, Lance Minor hoped to recognize how his old childhood shaped him while passing on the good parts and breaking the cycle of trauma. Photo courtesy of the author.

Buried Kirk in May of ’96.

He was the first brother gone and the beginning of my survivor’s remorse. He replaced me when I left 2/8, and he died with 13 others in a helicopter crash. Blades of a Cobra ripped through the fuselage of their Frog with vicious impact. Chidester was there too, and I wonder what Kirk was thinking, sitting in my seat, when the guy across from him burst into pieces for no reason.

We fished out his flak from the black Carolina swamp water, his torso still inside. This time the copper was mixed with jet fuel and smoke while a hurricane brewed off the coast.

Terry was the second, his leg taken by an improvised explosive device in a sandstorm on his fourth tour in Iraq. Weeks before he got hit he called me on a maritime satellite communications device.

“Got a bad feeling about this one, brother. I needed to call you before I talked to Jen.”

Not long after, I sat at my cushy desk at U.S. Southern Command Headquarters in Miami-Dade County and read the message on the Secret Internet Protocol Router Network: “Friendly WIA, Roadside IED, E7, TK Ball, BKA, MEDEVAC to Lundstahl.”

He kept his promise to come home when they rolled him into Bethesda. President Bush pinned on his medal, and the resident doctor fucked up his feeding tube. Terry bled out on the table.

Wilfred Owens was right about the old lie: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. There is no logic or glory in why some die and I live, but I do.

So my turn came.

In Afghanistan for 10 months, but not to fight. I stood on the flight line at Camp Bastion every time we got the call for a ramp ceremony to honor those who did.

Flights coming and going at all hours. The dead board via flag-draped boxes, finally bound for home while the living form a gauntlet listening to Taps and the jarring report of the 21-gun salute. The wind kicks up unrelenting moon dust, and you can smell the heat.

Lance Minor spent 10 months at Camp Bastion in Afghanistan, where he stood on the flight line every time a fallen service member passed through. Photo courtesy of the author.

Each time I raise my slow salute I think about who is in the latest box. Kirk, Chidester, and Terry. Were their deaths more noble than the Trucker and Jack?

“Real Marines” fight the good fight outside the wire, and me on this side of the fence with my leisurely walk from my can past the military working dog kennels. Even the dogs leave the wire while I march 421 steps to the vault—my own plywood box—my own “Club Med,” and once again I find myself longing to be on a plane.

See, the big boxes are filled with volunteers; we know the risk. But the first sight of a small box, as hardened as my soul was, as comfortable as I was with the darkness, as much as I rationalized our duty—brave or mundane, sweet or bitter—the sight of that canine box, filled with wasted loyalty and innocent eagerness to please, wracked my soul with vicious impact.

The blowing moon dust clung to my first tears in years.

You see, death is easy once it’s done; the dead can’t feel sorry. The pain only remains for the living. Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. There is no logic in naive glory.

My chance to face death came later, unexpected, and trivial.

Long before Covid-19, I fought the Swine Flu. H1N1. No, more like H1 … FU. My lungs filling with fluid, I fought. Oxygen saturation levels dropped to 72 before I went to the emergency room.

Long before Covid-19, Lance Minor contracted swine flu and spent seven weeks in a medically induced coma. Photo courtesy of the author.

“I’ve never had anyone ask to be intubated,” the pulmonologist told me, but I did. I was tired and needed to rest.

“No. … put me under, let me sleep, and I’ll wake back up and keep fighting. I’m a warrior, Doc.”

But am I? I’m sure he heard the resignation in my voice.

I was in a coma for seven weeks, and when I awoke I had to learn how to walk and talk again. Looking down at my withered legs I told my daughter, I can fix this.

I did.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

“Ever onward, never quit.” Kirk’s words are written on my mirror, overlayed against my aging face, a reminder of busted shins and broken boys, the ones we lost, my dusty tears, and the cost of other failures throughout my years.

This is the crucible that forged me, but I am no piece of steel.

No. … none of us are.

But we are tough. That we are.

Comments are closed.