In an Unsteady Peace, Soldiers Built Bridges With Hankies, C Rations, and Salami

In March 1960, I reported to Delta Company, 17th Infantry, Seventh Infantry Division, based at Camp Kaiser, a smallish compound of low cinder block buildings and Quonset huts some 60 miles north of Seoul and about 30 miles from the muzzles of North Korean artillery arrayed along their side of the Demilitarized Zone. I was an SP4 infantryman and assigned to Third Platoon’s Weapons Squad as a machine gunner on the WWII veteran Browning .30 caliber.

Our Seventh Division was at about 70% authorized strength. The Republic of Korea Army troops known as KATUSAs, or Korean Augmentation to the U.S. Army, made up the shortfall in fighting men. The KATUSAs had their own mess and were led by a bilingual Korean Army officer—Lt. Yun in Delta Company, a slight, bespectacled man with a ferocious temper.

The two KATUSAs assigned to my squad, Pfcs. Kim and Chun, served as ammunition bearers, one for each of our two machine guns. Two GIs also served as ammo bearers. I made sure everyone in my section, including Chun, knew how to properly site the gun, load it, clean it, and fire it effectively. It was peacetime, but we all understood the shooting war that had stopped seven years earlier was merely on hiatus, not finished. Our officers told us almost every week that North Korea could resume hostilities at any moment, with or without a reason. It was our job to be ready for either case.

Should hostilities resume, Delta Company’s mission was to hold a section of the main supply route—one of three unpaved roads running south to Seoul—for three days. Our sister 17th Infantry companies each had an adjacent sector to hold. The bigger picture was that the generals at Eighth Army, our higher headquarters, believed that Seoul could be evacuated of its noncombatants in three days. Our task was to give them those days.

In March 1960—seven short years after the end of the Korean War—Marvin Wolf reported to Camp Kaiser in South Korea as an SP4 infantryman assigned as a machine gunner. Photo courtesy of the author.

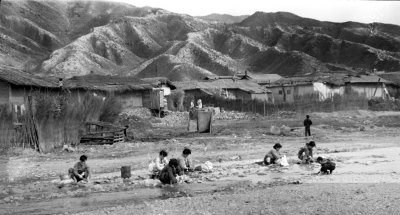

Between us and the DMZ was a Republic of Korea Army division. We were told that few of that division’s officers and noncoms had any combat experience. Most were conscripts. Accordingly, our officers feared that if the North Koreans attacked, the Republic of Korea Army division would simply melt away in a few hours.

But we needed to hold for three days. Our officers were blunt: If we could hold that long and allow Seoul’s civilian populace to escape, we would then be on our own—and few of us should expect to avoid death or capture. Thus motivated, we trained hard. Very hard. I walked holes in three sets of boots, ate everything I could get my hands on, and lost 10 pounds in the first seven months.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

As part of our readiness drills, once a month, usually the last week of the month, a siren roused us from our bunks in the wee hours. We had 10 minutes to dress, get our weapons from the arms room, accept the issue of a basic load of live ammunition—200 rounds for riflemen, 400 for each machine gun, and six rounds for each bazooka, plus a box of C rations—and begin climbing the heights behind our base. This event, and what followed, was called “an alert.”

We had 90 minutes to climb the small alp behind our base, then navigate a goat path up and down two more hills to reach the heights above our sector of the road. There we had excavated several trench lines. We took up defensive positions in them.

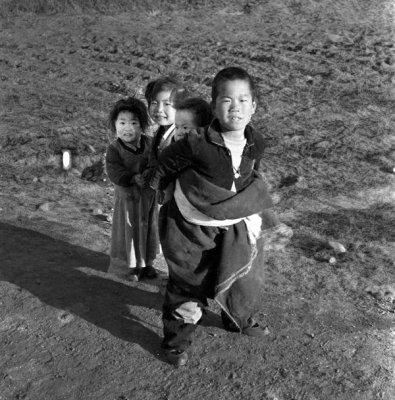

For a drill, we would receive a brief critique, then start walking back to our compound. The most difficult part of this journey, for me at least, was just before we reached the heights above the road. There we passed through a tiny, impoverished village of some 20 mud huts with roofs thatched with rice stalks. As we walked, weary from our long climb and heavy loads, it seemed that every resident of the community stood in their doorway, silent and expressionless, watching us.

Following monthly readiness drills, Delta Company passed through a small impoverished village where, it seemed, every kid needed their nose wiped. Photo courtesy of the author.

The youngest wore only some kind of filthy shirt, with their bottoms bare. Many older children wore thin poplin shirts sewn from discarded ammunition bandoleers. Those not barefoot wore rubber shoes without socks, some insulated with newspaper. The nose of every child, and a few of the adults, dripped with long wads of greenish mucus. Every time I saw those villagers, I told myself, “These people have nothing,” and felt very sad for them.

One day in September, just after we returned from an alert march, Sgt. 1st Class Gomez, our platoon sergeant, called a meeting. Gomez was from Puerto Rico. Grizzled and about 40, he had fought in WWII and in Korea with the 65th Regiment of the Third Infantry Division.

“Men,” he began. “Do you look at the people in that village when we walk through every month? Do you see how poor they are?”

Heads nodded.

“I want each of you to do something. I want you to go to the PX and buy a packet of two white linen handkerchiefs. And the next time we walk through that village, when you see a kid who needs his nose wiped, hand his mother those hankies.”

“Can’t we bring them some food, Sarge?” asked one of the men in my squad.

“I’m working on that,” he said. Then he looked at me.

“Wolf, doesn’t your mom send you a big salami every month?”

“She does,” I said. He knew as well as anyone that when that kosher salami arrived, I borrowed a big knife from the mess hall and started slicing. Every man in the platoon, including the KATUSAs, got a slice or two until it was all gone. I rarely got more than a slice myself—but that was long the unwritten rule concerning food from home: You shared. You made sure your buddies got as much as you did, or more. Everyone did the same.

The tiny, impoverished village of some 20 mud huts near Camp Kaiser, a U.S. Army compound about six miles north of Seoul, Korea, and 30 miles from North Korea’s side of the Demilitarized Zone. Photo courtesy of the author.

“Next time you get one, let me know. I’ll get Cookie to save it in the kitchen fridge and we’ll give it to the villagers. OK?”

I shrugged. “Anything to help.”

But before my next salami arrived, before Gomez could round up C rations to give the villagers, a whole week earlier than usual, we had another alert. When we passed through the village, I found a graying mother with five or six kids clustered around her skirts, and after taking a dirty hanky from my pocket and blowing my nose, I handed this woman a cellophane packet of two new linen handkerchiefs. She took the packet, expressionless, and I moved on.

About five weeks later we were back, again just at sunrise, and this time we handed every adult a package of C rations. In each cardboard box were the following: Some kind of hard bread; a main course, which might be spaghetti and meatballs, beef stew, franks and beans, tuna and noodles, ham and lima beans, chopped ham and eggs, or something similar, plus a few crackers; chocolate or hard candy; a pack of four cigarettes; chewing gum; instant coffee; and a small roll of toilet paper. Again, the families accepted our gifts stoically.

Children in a village near Camp Kaiser. Photo courtesy of the author.

About a month later, an elderly Korean man in white robes and a tall horsehide hat appeared at the front gate. Lt. Yun was sent for, and after a short conversation, he escorted the man onto the base and to our company orderly room. As it happened, all four of our unit’s officers were there. The elder had come to deliver an invitation, and after a short conversation with Lt. Yun translating, our visitor was escorted to the front gate and left.

Three days later, our four officers—Capt. Messier, the company commander; Lt. Brown, the executive officer; and our two platoon lieutenants, along with the first sergeant and me, set out in two jeeps for a village on the other side of the road from the trench line we manned during alerts.

I was there for one reason only: The XO told me to bring my camera and gave me a roll of 35mm black-and-white film. We were invited to a wedding reception and I was to take photos of the bride, groom, and their families, and then leave them the film.

I also brought a salami, professionally sliced by our mess sergeant. The officers had each donated $10 in won, the local currency, and placed it in an envelope. The elder met us at the main supply route and guided us to a prosperous village watered by a mountain spring in a little hollow across the road from our trenches. Surrounded by expansive rice paddies, the houses were of stone with tile roofs. Rows of apple and pear trees shaded some houses.

“It was peacetime, but we all understood the shooting war that had stopped seven years earlier was merely on hiatus, not finished. Our officers told us almost every week that North Korea could resume hostilities at any moment,” writes Marvin Wolf. Photo courtesy of the author.

We met the bride, a tiny woman in her late teens, in a kind of meeting house. She wore a stunning white hanbok of white linen artfully sewn from dozens of immaculate linen squares. The groom, a robust man in his late 20s, was traditionally dressed. Capt. Messier handed the bride the bulging envelope and I set my sliced salami on the table, which was otherwise covered with old but beautiful plates and bowls piled high with what we Americans knew were C ration entrees. Hot (instant) coffee was poured from a pitcher. American cigarettes were available in tiny urns around the room.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

We stayed only a short time. My understanding was that the groom was from the village we were visiting, and the bride was from the dirt-poor hamlet that we walked through on alert mornings.

Another month passed before our next alert.

This time, however, because a bunch of ignorant but well-meaning GIs had thought to help this dirt-poor village, and had thus allowed its daughter to hold her head high as she wed in a gorgeous gown and then treated her new in-laws to an unexpected feast of expensive Western delicacies, Delta company received a hero’s welcome.

As we walked the narrow pathway, men, women, and children waving tiny American flags stood smiling at us from every doorway. And every kid needed his nose wiped.

Comments are closed.