‘A Violent Transition’—Mental Health Care Lacks Military Cultural Understanding

In 2010, Seth Allard, a Marine Corps veteran and member of the Sault Saint Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, drove past a parking lot full of cars outside a local Catholic Church in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and wondered why such a large group gathered at the church.

It wasn’t a Sunday morning, Allard remembers thinking. He asked the tribal elder he rode with what was happening.

“Oh, that’s a suicide support group,” the elder told Allard.

Allard says he was struck at the time: Did tribal members struggle so much with suicide? Over the years, the issue stuck with him.

Looking back, Allard realizes they dealt with the anxiety, depression, and economic uncertainty that strikes many tribes across the United States. That ride with his elder served as a catalyst for him to study suicide prevention.

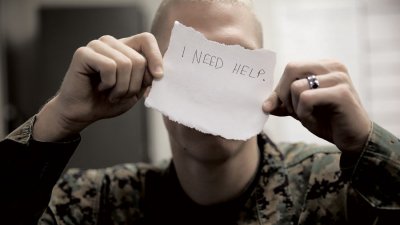

The Marine Corps announced the Marine Intercept Program. The program goes hand-in-hand with the Suicide Prevention Program, providing follow-up care and counseling for Marines who have attempted suicide or had suicidal ideations. U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Sarah Cherry.

“I sort of got sucked into it, and then I realized that there were these instances of suicide, suicidal thinking, depression, risk, and tragedy,” Allard tells The War Horse. “The more I read into it, the more I just got this feeling that these were stories that were not being told in a way that they deserve to be told, with all the complexity that is involved.”

Allard combined the moment and his experience in the Marines to dive into the topic of suicide prevention as a doctorate student of social work at Wayne State University. He recently published a paper that states that, while the Defense Department spends more on suicide research than any other entity in the United States, research and programs don’t pay enough attention to how service members live their lives, communicate with each other, or interact with the organizations and institutions in their lives. All of this has led him to believe a better understanding of how service members and veterans live their daily lives—their culture, rather than sanitized statistics and studies—could help prevent death by suicide in this community.

While veteran suicide rates appear to be falling, according to Veterans Affairs, active-duty suicide rates went up the first quarter of 2023—and both groups saw their suicide rates increase after the attacks on 9/11.

But even as VA and the Defense Department increase their resources, people still feel as if they’ve been left on their own—particularly as they transition from active-duty status to veteran status. And the military continues to face accusations of a machismo culture that doesn’t allow service members to ask for help out of a fear of looking “weak”—an issue the Navy and Marine Corps is working to address with the recently enacted Brandon Act, which allows troops to seek out care confidentially any time they need it.

Military culture also emphasizes the idea that “if you haven’t served, you don’t understand,” leading to complications in treatment, particularly if a therapist doesn’t know a Chinook from an iron duck, Allard says. Service members and veterans avoid treatment if they believe it will “retraumatize” them, or if they have a hard time making an appointment. Perhaps, Allard says, cultural change should start with boot camp and basic training, where as people are resocialized to meet the military’s standards, they also learn to feel safe seeking help or simply talking about the stress they face daily, in the war zone or during a line inspection or when that first paycheck doesn’t quite stretch until the end of the month.

But the military also could take a harder look at itself, Allard says, as well as the hard issues that contribute to death by suicide, including sexual assault, hazing, and toxic leadership.

“With the Marine Corps, when you don’t understand its culture, then you don’t understand people’s social views and the social history of an organization, and you lose out on how that culture is going to impact your policy,” Allard says.

‘Now You’re on Your Own’

As veterans leave service, especially younger veterans, they may lack a strong social network in their new communities.

Allard calls this a “violent transition.”

“You go from having every aspect of your life controlled, organized, and structured by this constantly present entity—which is the Marine Corps—to freedom,” Allard says. “It highlights this kind of weird effect of an emptiness, because you were so reliant on that social structure, and now you’re on your own.”

This can leave veterans with an identity crisis.

“Marines are trained to believe and think of themselves as sort of modern-day Spartans who are separate and distinct and have a higher moral code than the rest of the country,” says David J. Morris, a former Marine, author, and English professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “So they get out and then that code really doesn’t fit very well.”

A type of “psychic numbing” sets in for many grunts in boot camp almost as a necessity to overcome the most grueling aspects, Morris says, adding that there needs to be a “deconditioning or a demilitarization of the mind” as they move to civilian life.

“The ‘embrace the suck’ mentality that’s part of boot camp and part of Marine culture—you have to learn to step outside that or move beyond it, because if you don’t—if you pretend that you don’t have emotions—you’re not learning from your experiences,” he says.

Morris finished serving as a Marine in the late 1990s, before the war on terror started. In 2007, after earning a degree in English, he embedded with a unit in Iraq. Members of that unit were struck by an IED in Baghdad, an event that would change Morris’s life and lead him to seek therapy for post-traumatic stress nearly four years later.

“One of the problems that I ran into in the VA is that it’s an academic psychology culture,” Morris says. “And that culture is completely at odds with Marine culture.”

Allard says suicide research and therapy itself should incorporate more of an anthropological approach so veterans don’t face such a jarring adjustment when they seek treatment. This would allow anthropologists to attend trainings, deploy with units in a limited fashion, and get a better grasp of what Marines and other service members face.

And, if anthropologists embed with active-duty service members, they could get a better understanding of the social systems and personal feelings of the troops to determine why the risk for suicide is high and what to do about it, Allard says.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

“What these movements and studies strongly suggest is that without the implementation and consistent support of internal cultural research, the Marine Corps will not be able to fully grasp the interrelated factors, conditions, and social perceptions that contribute to the decision to commit suicide or, for that matter, any salient issue that affects Marines, such as sexual assault, discrimination, hazing, or toxic leadership,” Allard writes in his study. “This will leave Marine leaders and individual Marines one step behind the cultural curve.”

‘It Matters for Veterans’

At VA, Morris received prolonged exposure therapy, which he, like a lot of veterans, found difficult. Veterans tell and retell their stories in a safe environment in the belief that it helps them process and organize their memories to a point that they can control them better. But it can feel retraumatizing, and it’s time-consuming.

Prolonged exposure therapy has worked for many veterans and is considered one of the best treatments for PTS. A January 2023 JAMA study conducted on 234 military personnel and veterans found prolonged exposure therapy used in three-week sessions reduced symptoms of post-traumatic stress in more than 60% of the patients.

“The [January 2023] study found that PTSD can be effectively treated in active duty military and veteran populations in three-week massed prolonged exposure and intensive outpatient program formats, with very low drop-out rates (e.g., 15% or less),” Alan Peterson, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Texas, San Antonio, told U.S. Medicine in a recent interview.

Peterson said prolonged exposure therapies typically involve once-a-week outpatient care and last 10 to 12 weeks. They have drop-out rates around 40% to 50%.

Research from Psychological Services journal found the reasons veterans drop out of prolonged exposure therapy range from appointment scheduling difficulties, aversion to their providers, belief that their symptoms are getting worse, and simply disliking it.

But Morris says his therapists, as well as a PTSD researcher he talked with, lacked basic Marine Corps cultural knowledge.

David Morris, a Marine Corps veteran, poses near Fallujah, Iraq, in 2007. Photo courtesy of Morris.

“[One] seemed to struggle with the concept of helicopters, generally,” Morris says. “It drove me nuts because she kept referring to it as ‘the craft.’ It was very agitating because she did not have a rudimentary understanding of what life [for] grunts was like.”

Morris’s experience touches on what Allard is studying: a lack of therapists who have a basic understanding of military culture. Few know what it is like to go through boot camp, to fight for your country, or to have bullets fly in your direction. A vast majority of veterans prefer a therapist who is also a veteran, a 2018 study found.

Because there’s a shortage of mental health workers in general, let alone veterans who are mental health workers, finding a veteran provider is tough—though the VA Vet Centers often have counselors who are veterans, according to VA. VA also has group therapy, where veterans talk with each other, as well as the BeThere peer assistance program, where veterans can speak with a peer coach.

VA also offers cultural competency training to civilian providers because so many veterans see civilian providers.

Sonya Norman, a staff psychologist at the San Diego Veteran Affairs Medical Center, tells The War Horse she has seen a demand for veteran therapists or therapists who have a greater knowledge and understanding of military service.

Sonya Norman, staff psychologist at the San Diego Veteran Affairs Medical Center. Photo courtesy of Norman.

“I’ve definitely seen that it matters for veterans, even if the clinician isn’t a veteran themselves, that [the therapists] kind of have some basic understanding of what the person experienced, the branches of the military, the types of jobs, types [of] deployments, [or] where they were,” Norman says. “And so, in the PTSD world, we have courses we’ve developed online for PTSD and military culture.”

A recent peer-reviewed study in the Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship found notable benefits for this type of training, including a more comfortable relationship between therapists and their clients, among other benefits. Graduate students at Jefferson University who took part in the study said they initially felt “insufficiently trained” to work with veterans, but after completing the training, they experienced a desire to counsel veterans.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

“Without the course experience … it is unlikely that these therapists would have changed their attitudes on their own,” the study found.

The Defense Department also offers training for health and behavioral health care providers who serve active-duty and veteran groups.

Chris Loftis, director of the Veteran Affairs and Defense Department Mental Health Collaboration at the office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. Photo courtesy of Loftis.

Chris Loftis, director of the Veteran Affairs and Defense Department Mental Health Collaboration at the office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, tells The War Horse there are several hours of cultural training available for therapists and counselors online. The Solid Start program, started in 2019, contacts new veterans three times during their first year of transition from active duty to veteran status to try to help veterans with the transition to civilian life, as well as to find health care, jobs, or help getting home loans.

But Allard says addressing the issue could begin early by changing the culture of the military.

“Culture, understood by Marines as their ‘warrior ethos,’ can be their greatest asset or their greatest threat,” Allard wrote in his study. “Repeating tired adages such as ‘Keep your friends close and your enemies closer’ can blind one to the enemy in the mirror.”

This War Horse feature was reported by Freddy Brewster, edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Headlines are by Abbie Bennett.

Comments are closed.