Israel is being harmed by Zionism’s oldest Jewish opponents – opinion

Zionism emerged at the end of the 19th century as an organized movement – with members, elected officials, a program, and all the other trappings of a political, diplomatic, and practical apparatus, including fundraising.

Zionism set an agenda for the Jewish people, inspired, motivated, and confirmed by the history of the Jewish people – its writings and prayers, and the constant attempts of individuals and groups to return to the Land of Israel, the Jewish homeland – despite their loss of independence and sovereignty throughout the centuries.

One hundred and twenty-six years ago, on August 29, 1897, the Basel Program was formulated. Zionism sought to establish a home for the Jewish people in the Land of Israel, known then to the world as British Mandate Palestine – by promoting settlement in the country and strengthening Jewish feeling and national consciousness.

This, of course, followed on the teachings in the Bible, the Talmud, and the rabbinic Midrash, and on the deliberations of the Geonim from the 7th-11th centuries regarding the corpus of halachic laws pertaining to the mitzvot ha’t’luyot ba’aretz (agricultural laws) for the most part applicable exclusively in the land of Israel. All this body of literature and actions created the uniqueness that is Jewish nationalism: custom, culture, language, and belief.

Messianic movements across the lands of the Diaspora and the prayers expressing the hope for an eventual return were the premise of the Zionist Jew.

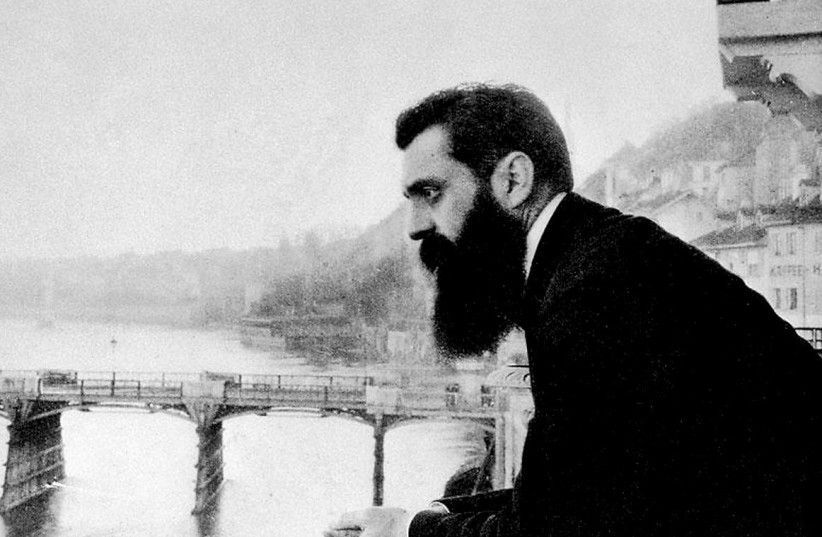

Theodor Herzl on the Hotel Les Trois in Basel, Switzerland. (The Bettman Archive) (credit: EPHRAIM MOSHE LILIEN)

Theodor Herzl on the Hotel Les Trois in Basel, Switzerland. (The Bettman Archive) (credit: EPHRAIM MOSHE LILIEN)The Jews who opposed Zionism

Yet, from the start, Zionism faced several elements of opposition.

The first was from the more conservative sectors of Orthodox Jewry that viewed Zionism as a multiple danger.

It was seen as part of the development of modernization that advocators of the Enlightenment had begun a century earlier, replacing Judaism with a Jewish kultura (culture). It was also a revolt against the traditional Diaspora attitude of awaiting messianic redemption stoically that was, at that time, first promoted by the fifth Chabad Rebbe, the Rashab, and then by the separatist Sighet Hassidic dynasty that became Satmar.

The second group represented the assimilationists – who rejected any national identity. A Jew, while (if at all) embracing forms of religious worship and practice, was first a German, Austrian, Frenchman, Russian, or an Englishman. The insistence of Zionists that Jews constituted a people and possessed a historic homeland was threatening to them.

So much did such people distance themselves and oppose Zionism, that the Balfour Declaration was almost sabotaged by leading British Jewish communal heads Lucien Wolf, Claude Montefiore, and David Alexander, as well as by the Jewish secretary of state for India, Edwin Montagu.

In the United States, as Robert Wistrich noted in his study, Zionism was a tangible threat to the security of Reform Judaism, the stream of the dominant German-Jewish establishment in the United States. They believed in the Diaspora as opposed to Palestine, in religion and not nationalism.

At the 1917 Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR), Zionism was fiercely attacked as a secular, political movement, and a resolution rejected “every non-religious or anti-religious interpretation of Judaism and of Israel’s mission in the world.”

The anti-Zionist resolution of the 1918 CCAR convention, read: “The ideal of the Jew is not the establishment of a Jewish state – not the reassertion of Jewish nationality which has long been outgrown… our survival as a people is [not] dependent upon the acceptance of Palestine as a homeland of the Jewish people.” In the autumn of 1918, Reform Rabbi Ephraim Frisch sent a telegram to US president Woodrow Wilson opposing a Jewish homeland. He founded “The National Committee of Rabbis Opposed to Zionism” with rabbis Schulman, Philipson, and Berkowitz to block US approval of the Balfour Declaration.

On March 9, 1919, 299 Reform rabbis intervened to attempt to halt president Woodrow Wilson from proclaiming agreement with the Balfour Declaration as adopted at the Versailles Peace Conference. Their letter was published in The New York Times.

The third group were those who, while also rejecting Judaism’s national characteristics, borrowed its messianic zeal, but transferred it to economic and social progress through the revolutionary Marxism.

The Jewish Bund was also founded in 1897, initiated by a young Jewish intelligentsia who had received a modern education, and was firmly rooted in Russian or Polish culture. Moreover, they were exposed to the ferment of immediate change even if through violence. The Bund encountered a problem when Vladimir Lenin viewed them as a national Jewish party developing independent political tendencies that were uniquely Jewish in character.

After 1917, some Bundist leaders assumed prominent positions in the Evsekstiia (the Jewish section of the Communist Party) which championed the eradication of Judaism and Zionism. After the Balfour Declaration, the ideological component of doikayt (“hereness”) came to the forefront. Doikayt insisted that the future of the Jewish people lay in the Diaspora, and the Bund saw itself as the guardian of secular Yiddish Jewish culture.

That ended with the Holocaust, but not before the Bundists assured that the socialist youth movement underground in the Warsaw Ghetto would not unite with the Beitar-Revisionist-led underground.

Today, just over a century and a quarter on, those three elements of opposition are still with us, exerting debilitating influences on Israel’s security, economy, diplomacy, and scientific achievements: the assimilationists, the separatist Orthodoxy, and the non-nationalist revolutionaries.

Zionism is still, to no small measure, at the beginning of its journey.

The writer is a researcher, analyst, and opinion commentator on political, cultural, and media issues.

Comments are closed.