Israel uncovers ancient Christian inscription from Book of Psalms

An excavation project at the remote site of Hyrcania in the Judean Desert that has unearthed a rare Byzantine Greek inscription paraphrasing a verse from the Book of Psalms is being carried out by archaeologists at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU). It is being performed to save remaining archaeological finds from antiquities looters who have been more active in recent years.

Hyrcania was an ancient fortress built by Hasmonean ruler John Hyrcanus or his son Alexander Jannaeus in the 2nd or 1st century BCE.

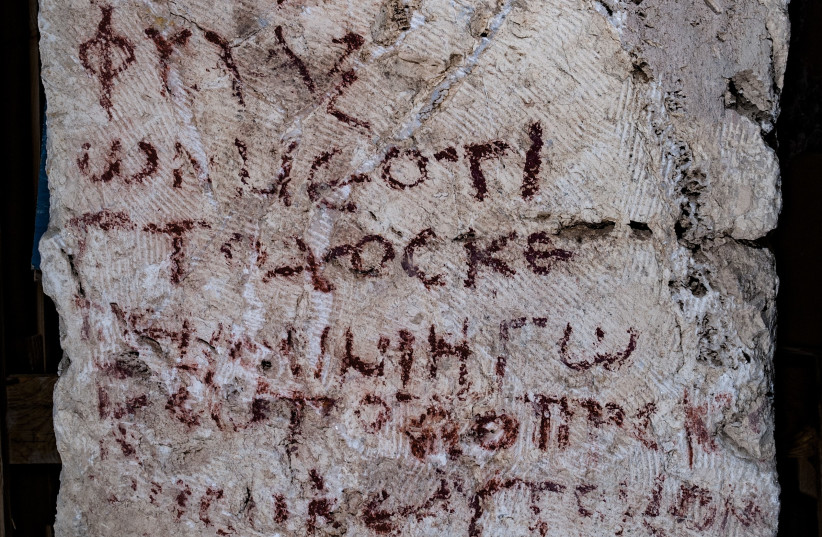

The readable text is a paraphrase of Psalms 86: 1–2, known as “a prayer of David.” While the original lines are “Hear me, Lord, and answer me, for I am poor and needy. Guard my life, for I am faithful to you,” the Hyrcania version reads: “Jesus Christ, guard me, for I am poor and needy.”

Built upon an imposing, artificially leveled hilltop situated about 17 kilometers southeast of Jerusalem and eight km southwest of Qumran and the Dead Sea, this was one of a series of desert fortresses that was later rebuilt and enlarged by Herod the Great. The most famous, and luxurious, of these strongholds are Masada and Herodium.

The inscription is in Koine Greek – biblical Greek or New Testament Greek that was the common supra-regional form of Greek spoken and written during the Hellenistic period, the Roman Empire, and the early Byzantine Empire that served as the lingua franca of much of the Mediterranean region and the Middle East during the following centuries.

Adorned with a cross, the Byzantine-era inscription was likely made by a knowledgeable monk and holds significance as a well-known prayer in the Masoretic text and Christian liturgy. An analysis of the script’s style suggests a dating no later than the first half of the 6th century CE, which was the height of the Byzantine era and with minor grammatical errors, revealing the scribe’s mother tongue to be Semitic.

Christian resettlement of the site

Shortly after the death of the latter in 4 BCE, Hyrcania lost its importance and was abandoned. It would then lie desolate for nearly half a millennium until the establishment of a small Christian monastery among its ruins in 492 CE by the monk Holy Sabbas, an expression of the monastic movement that took shape in the Judean Desert with the rise of the Byzantine period.

Dubbed Kastellion, or “Little Castle” in Greek, the monastery remained active past the Islamic conquest of Byzantine Palestine around 635 CE but was apparently abandoned by the early 9th century. The site is known also by its Arabic moniker, Khirbet el-Mird (“Ruins of the Fortress).” Attempts were made in the 1930s to revive the monastery, but harassment by local Bedouins cut short the venture.

Although a few isolated investigations of the site had been sporadically attempted in the past, no methodological, academic archaeological excavation had ever been conducted until now. Complex access and logistics have long played a role. But recently, a HU team led by Dr. Oren Gutfeld and Michal Haber, with the support of Carson-Newman University (Jefferson City, Tennessee) and American Veterans Archaeological Recovery, spent four weeks at the site, uncovering key evidence of the site’s remarkable history.

During this initial “pilot” season, efforts were focused mostly on two key areas. In the southeastern corner of the summit, a segment of the prominent upper fortification line was uncovered – a vital component of the Second Temple-period fortress dating back to the late 2nd or 1st century BCE. This discovery prompted Gutfeld to note: “There are certain architectural elements within these fortifications that strongly recall those of Herodium – all part of Herod’s extraordinary vision. It’s quite possible that the construction was even overseen by the same engineers and planners. It’s not by chance that we call Hyrcania ‘Herodium’s little sister.’ ”

In the northeast, the team peeled away a deep collapse layer of building stones to unearth an elongated hall lined with piers, part of the lower level of an expansive compound constructed of finely drafted stones. Its original date of construction has yet to be determined, though it likely comprised part of the monastery.

Over the course of excavation, a sizeable building stone was discovered lying on the plastered floor of the hall, bearing lines of text painted in red with a simple cross at its peak. Haber and Gutfeld immediately recognized the inscription as written in the New Testament’s Koine Greek but called on their colleague, expert epigraphist Dr. Avner Ecker of Bar-Ilan University, to decipher it.

Ecker explained that “this psalm holds a special place in the Masoretic text as a designated prayer and is notably one of the most frequently recited psalms in Christian liturgy. Thus, the monk drew a graffito of a cross onto the wall, accompanied by a prayer with which he was very familiar.” Judging by the epigraphic style, he assigned the inscription a date within the first half of the 6th century CE. Ecker also pointed out the presence of a few grammatical errors typical of Byzantine Palestine that can be attributed to individuals whose native language was a Semitic one. He suggested that “these minor errors indicate that the priest was not a native Greek speaker, but likely someone from the region who was raised speaking a Semitic language.”

A few days following this initial discovery, an additional inscription was found in close proximity. It was also inscribed on a building stone from a collapsed wall and is currently undergoing analysis. Michal Haber emphasizes the profound significance of these findings, stating that “few items hold such importance in the historical and archaeological record as do inscriptions – and it must be stressed that these are virtually the first examples from the site to have originated in an orderly, documented context. We are familiar with the papyrus fragments that came to light in the early 1950s, but they are all of shaky, unreliable provenance. These recent discoveries are truly exceptional.”

In addition, a child-sized gold ring, a little over one centimeter in diameter and adorned with a turquoise stone, was found on site. What adds to the special nature of the discovery is the miniature inscription incised in Arabic Kufic script on the stone. Dr. Nitzan Amitai-Preiss, an expert in Early Arabic epigraphy at HU, was able to decipher the inscription as “مَا شَاءَ ٱللَّٰهُ” (Mashallah), which translates to “God has willed it.” She dated the script style to the time of the Umayyad caliphate, which reigned during the 7th and 8th centuries CE. Amitai-Preiss also observed a unique feature in the inscription – two of the three words were mirror images, strongly suggesting that the ring may have originally served as a seal.

The origin of the turquoise stone itself adds another layer of historical intrigue. It was likely sourced in the newly conquered territory of the Sassanid Empire (modern-day Iran), part of the expanding Umayyad caliphate. The exact path this remarkable artifact took to reach Hyrcania remains a mystery, as is the identity of whoever wore it.

The team is eagerly anticipating the next excavation season scheduled for early 2024 that will see the collaborative effort with Carson-Newman University and American Veterans Archaeological Recovery continue.

The staff officer for archaeology at the Civil Administration of Judea and Samaria, Benny Har-Even commented: “The Civil Administration will continue its tireless efforts to preserve and develop the archaeological sites throughout Judea and Samaria. We are delighted to work in cooperation with leading Israeli academic institutions and all parties involved in the archaeology of the Land of Israel to reveal the ancient and rich past of the area.”

Dr. Stephen Humphreys, the founder and CEO of American Veterans Archaeological Recovery (AVAR), commented, “Our organization serves to provide military veterans with challenging fieldwork opportunities, then giving them the support tools and training they need to excel.”

“At Hyrcania, we saw the entire project team bond over the physical challenges and excitement of excavating this exceptional site. The training our veterans received at the site from the HU team will also make them more employable and better prepared to continue engaging with the field.”

Alongside their excitement, Haber and Gutfeld remain acutely aware of the complexities of safeguarding such a site. They emphasize the support they have received from the Staff Office of Archaeology of the Civil Administration in combating the ongoing phenomenon of antiquities looting.

They concluded: “We are aware that our excavations will draw the attention of looters. The problem persists; it was here before us and will likely continue after us, underscoring the need for academic excavation—particularly in such a sensitive site as Hyrcania, though this is just one example. We are simply trying to stay a few steps ahead.”

Comments are closed.