They Did Everything They Could to Make Her Fail. But They Could Not Break Her.

Her fate was sealed before she even stepped off the plane at Agana Airport (Guam) in 1979. That’s a fact. The officers and chiefs had decided that the ensign was going to fail—they were not going to let a female line officer tell them what to do.

Seventy sets of eyes—even the military band upstairs—stared at the earnest man in the white uniform at the podium. It was Aug. 16, 2016, in an art deco building on Naval Station Norfolk, and Postal Clerk Senior Chief Charles Stancil (retired) was opening my retirement ceremony.

Captain R. Van signs a contract for Officer Candidate School in 1979 while her father and uncle look on. Photo courtesy of the author.

Thinking back to my departure for that remote island decades before, I remembered my father and Uncle Ray, a retired boatswain mate chief who wore his service dress blues to see me off, physically pushing me onto the plane. Had it happened that way? That inglorious scene sticks in my mind but I can’t tell if it stems from what really happened or my bowel-spewing fear of boarding that plane.

What was I afraid of? Plenty. I had been a lackluster officer-in-training at the three-month school, which did not bode well for my performance as a real commissioned officer. My performance had stunk during a one-week administration class. I also had a “99.99% chance” of becoming an alcoholic—at least according to the instructor of the week-long Drug and Alcohol Advisor class I’d also taken.

Things have changed since I enlisted in 1971. In my Navy, going out and getting in a fight with a Marine in a bar was called fun. Now you guys call it assault.

Some questioned the choice of this speaker—a sailor and senior chief from the enlisted ranks, albeit well-decorated. Still, a sailor commenting on an officer’s career. …

It wasn’t the first time I had been told that my decision wasn’t the prescribed way, but I was adamant about fulfilling a promise made between us 36 years earlier and 8,000 miles away. And somehow, it seemed fitting that there would be controversy, even on my last day in uniform.

In my Navy, we didn’t have relationships like y’all do. We called it shacking up.

In my Navy, we didn’t have issues, we had problems that needed to be solved.

The Navy experienced important changes in the 1970s. Blacks, Hispanics, and Filipinos could leave the messman rating (they did the cooking, cleaning, and laundry) for other careers. It was a turbulent time in the Navy. There were a lot of problems with that transition; the racial tension was thick. Even though the Vietnam War had ended in 1975, we were still feeling the aftereffects of that 20-year turmoil. It was not pretty.

In high school, two events piqued my interest in the Navy. In 1976, the first group of women were admitted to the U.S. Naval Academy. Two years later, in 1978, the first Navy ship allowed nonmedical women as part of its crew. Fifty-five officers and 375 enlisted women were assigned to 21 ships in both the Atlantic and Pacific fleets that year. But it was the recession and undesirable job prospects that propelled me to a military recruiter in 1979.

About this same time, the Navy, in all its wisdom, decided to send female line officers overseas and on ships. We had just experienced—and were still reeling from—this gigantic upheaval in racial relations, and now we had to deal with women. I had seen female officers in the Navy—an attorney and one or two female doctors, and, of course, Navy nurses—but that was it.

To me, race and gender issues are intrinsically connected. As one astute observer noted, “We’re not there if we’re still counting.”

I was a first-class postal clerk, a midlevel sailor, running the mail service at Naval Station Guam, from 1979 to 1981. Word got out that Ensign Van was due to report—a female line officer, a fresh-caught ensign straight from college, maybe 21 or 22 years old.

Ladies and gentlemen, I’m not here today to entertain you. I’m here today to tell you what exactly that was like and what happened because I was there, and I lived every moment of it. The first female line officer was reporting to Naval Station, Guam. Holy cow.

They did everything they could—I’m ashamed to say myself too—to make her fail. Whatever Ensign Van did, it wasn’t right. Unmerciful. The officers, the chiefs, the sailors, and especially the wives—it was just vicious.

Line officers run the Navy’s operational assets. That’s why recruiting women as line officers but not allowing them to function as such was an organizational misstep with dire consequences for all hands: false expectations, unexplained policies that changed capriciously, and insufficient foresight, funding, and follow-through on career design for women. It’s a small wonder so many trashed their skirts after their initial tours.

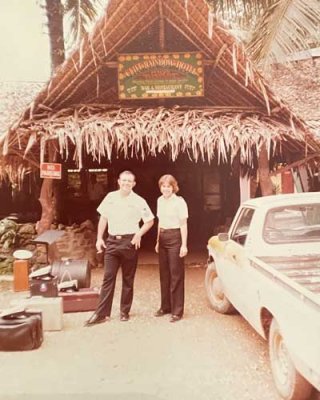

Captain R. Van with Charles Jonathon Stancil on Ponape. He became a lifelong friend who spoke at her retirement ceremony in 2016. Photo courtesy of the author.

Fifteen months in Guam had lagged like 15 years—reports inexplicably lost, correspondence delayed for no apparent reason. Ignoring the chain of command. I’d confronted the commanding officer once after he repeatedly spoke to my administrative assistant on department matters, cutting me out of the loop.

It was a short conversation.

I finally had to laugh about some of the projects assigned to me, like when the task of designing and conducting a traffic survey of Guam appeared on my desk. I don’t recall if this was before or after I had to redecorate the admiral’s quarters. Sure, why not? If I suggested, for example, that the base engineer might be better suited to the traffic survey, I was shirking my duties, not a team player. Obviously, I was not capable of keeping up with the work, a whiner.

If she showed up at a Navy function by herself, she was a lesbian. If she brought a male counterpart to one event and then another fellow the next time, she was loose. When that tactic didn’t work—didn’t break her—they gossiped that she was sleeping around with married men. Van heard these and did not break. She shook her head at their immaturity. In fact, she finally started her own rumor: that she was pregnant, father unknown.

Capt. R Van with the personnel division at Naval Station Guam in November 1980. Photo courtesy of the author.

I was a mess. I would shower immediately upon returning to my Bachelor Officer Quarters matchbox room after work. And cry. I ate too much at the mess hall. I drank too much when I went out. My knees and side still hurt from officer training. Then I wrenched my back lifting too much weight too soon at the base gym. The pain added to my stress.

I stayed busy. In addition to working full time and standing duty a few times a month, I taught community college classes at night. I remember walking around with a heavy book that I would drop on the floor behind a student who was dozing off—even though I empathized with those who’d worked all day and still chose to further their education.

This will give you an idea of what she had to put up with on a day-by-day basis. One of the senior officers drank at the officers’ quarters bar frequently—OK, daily—a common area that the ensign had to pass on the way to her living quarters. He shouted at her every time to join him for some drinks—and other ungentlemanly comments. Van sought advice about this unpleasant situation from the base chaplain. The chaplain suggested that they become lovers because then the senior officer would leave her alone.

Captain R. Van with her uncle, who received a duty dollar upon her commissioning as an officer. Photo courtesy of the author.

I wish it hadn’t been true. I remember I felt like I was watching a movie, with the soggy older man, a lieutenant, leaning over the desk to touch me, a gesture I found abhorrent. The base chaplain was our spiritual leader and married with children, and here he was making lewd suggestions to me in my office. I quickly escorted him out. Part of me had wanted to lock the door and scream.

All I had was chutzpah and what I learned about the world from books. Lesson number one: Nothing comes of affairs with married men. I had already suggested to several attractive men to look me up when the ink was dry on their divorce papers.

Anyone who has been in the United States military knows that it takes something special to bond with your coworkers. There is a certain trust that you have—or in my Navy, we had to become shipmates. Because of her determination, I was starting to break down and just thinking of trusting her. She was determined and I had to respect that.

If you could have seen the hell she walked through with grace and dignity—and carried forward—only an idiot could not respect that grit—and we had a lot of idiots on Naval Station Guam, starting with our commanding officer, all the way down. I’m not saying anything to you that I haven’t said to their faces.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

That was news. It took a lot of guts, maybe a death wish, for a sailor to speak so bluntly to senior staff, especially officers up the chain of command. Our commanding officer’s nickname wasn’t “Mad Dog” for nothing.

This is what changed my mind about this young officer. I was a junior officer of the watch one Saturday night. Now, in my Navy, the United States Marines guarded the base perimeter, controlling access at the gate, and the tradition in the Navy was that no matter what, you didn’t mess with that Marine that day. Their job was hard enough already; half of them had already been to ’Nam and back; they had had enough. Leave them alone; respect them for those 15 seconds to get through the gate. Other than that, they were fair game.

I reached under my seat for the bottled water, wishing it was something stronger. Charlie continued.

Ensign Van was officer of the day, who monitors the day’s events as dictated by the commanding officer, oversees those standing watch, and ensures good order and discipline at the base. She came outside to where I was smoking a butt and said, “Petty Officer Stancil, we have a problem at the main gate. There’s a sailor giving the corporal trouble.”

I told the messenger of the watch—“C’mon man”—and the three of us piled into the duty pickup with a red light on top for the half-mile ride to the main gate.

A disheveled seaman, who looked even younger than Ensign Van, was mouthing off to the staid corporal of the guard when we pulled up. The Marine stood rigidly in the small gatehouse, his eyes tracking the errant sailor. I was relieved to see his pistol still holstered, as I knew it was loaded.

“What do you suggest?” she asked me.

“I got it, Ensign.” I got that sailor, and I took him behind the truck. We called that family-room counseling. I beat him to a pulp and threw him in the back of the truck.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

Such unauthorized discipline was meant to garner compliance, improve performance, or exact revenge. Leadership traditionally turned a blind eye to this deck-plate justice. It was a vestige of the old Navy.

I asked the corporal of the guard, “Are we good?” He nodded.

Now, I’m sitting in the truck on the way back, looking at the three blue crows on my left sleeve that indicate my rank as a first-class petty officer. I’m thinking that one of two things might happen. The commanding officer rips one or two crows off my sleeve, reducing me to a second- or third-class petty officer. Being reduced meant less money, less prestige, huge embarrassment. Or I trust this young ensign.

I looked her right in the eye. “What did you see, ma’am?”

She looked me right back. “Stancil, I didn’t see anything.”

And I knew right then and there she was not only an officer, she was a naval officer, she was a naval officer of the line, and I trusted her in my Navy.

Comments are closed.