‘The System Is Not Built for You,’ VA Doctors Told Him. They Weren’t Wrong.

In the summer of 2015, some six months after exiting the Marine Corps, I took a run, not unlike hundreds before it. This time, though, I heard something snap in my back and collapsed to the ground. After five, maybe 10 minutes, I stood and hobbled back to my apartment, believing I’d severely strained a muscle.

Yet from that day forward, the pain originating from my lower lumbar turned the simple task of tying my shoes into a breathless chore. For the next five years, nearly every time I descended to tie my shoe’s limp laces my spine tingled hot. No matter how quickly I’d flip those floppy cotton strings one over another, heat spread down my leg and up into my brain and I’d abandon the laces whatever their state.

Once upright, the pain would subside to tolerable. On a good day, a single shoe required two dives to tie. On more than one occasion I forewent errands, plans with friends, or travel because I could not complete dives three, four, or five.

Marines in 3/2 conduct a squad-sized exercise during a 2015 deployment in South Korea. Photo courtesy of Nate Eckman.

Nights became insomniac haunts. At first, the pain mimicked a feeding, like my discs were being eaten by the surrounding vertebrae, like piranhas sharing the same bait. Then it began to feel as if the bait had been consumed, and the ravenous bones in my spine nibbled at each other after the slightest movement. This feeding decimated all reprieve. A month after that run there was no position in which I existed without pain—not even during sleep. Each chattering of vertebrae, every contact with nearby nerves, made my face wince and my pulse race, often dampening my skin in beads of sweat. It was this pain that taunted terminal treatments; it could only wane through a variety of self-medicating numbing agents. A sober life was painful, one drunken and drugged serenadingly sweet.

After two months, the pain grew intolerable. I reached out to the Department of Veterans Affairs in New York City and learned that the wait list for new patient appointments was three months. I imagined I’d lose my mind before that. I opted for physical therapy nearby. I was not yet aware of the reasons for my pain—I knew only that my back, to no exaggeration, was disabling and that the short sessions with a physical therapist helped. For as little as $300 a month, I could consistently tie my shoes with just two dives. At the time, it was worth it.

That next year, I turned exclusively to yoga and swimming for exercise. I could again tie my shoes and sleep without interruption. One day, I ran halfway across the street to beat a red light and didn’t wince. For some weeks I thought I’d healed. But every couple of months over the next four years I’d sleep crooked or step too aggressively, setting ablaze again that fire at the base of my spine. Finally, I had to admit I wasn’t healing, but rather masquerading.

Troops prepare for night raid training in Southeast Asia. Photo courtesy of Nate Eckman.

A move to Texas finally gave me the opportunity to heal. I called the VA in Austin, and they fit me in that week. My primary care physician, concerned about my symptoms, sought a same-day MRI. It was then I learned the source of my pain was not, as I’d believed, an overactive psoas or strained muscle. I had two herniated discs, including one—between my L5 and S1—that was degenerative.

Degenerative discs are often caused by a repetition of stressful events. While in service, I’d attended physical therapy multiple times for injuries in my hips, lower back, and knees. But I’d never chalked those pains up to anything more than normal wear and tear and never sought a diagnosis or imaging. Until that stride that left me in a heap on the ground in the summer of 2015, some amount of pain was something I’d accepted, something that ebbed and flowed.

The VA diagnosis gave me access to other specialists within VA health care, all of whom conclusively recommended I seek back surgery. From what I’d read, anyone who needed back surgery at my age would need more than one.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

I protested. I’d read about all kinds of other therapies where spines in much worse shape than mine were healed. I asked about oxygenation chambers, electrical muscle stimulation, decompression therapy, targeted strength training, dry needling, even marijuana and stem cells. In the half-dozen visits after my MRI, I was offered an electric muscle stimulator and a pamphlet of exercises that could be found on the first page of a Google search for “movements to help a hurt back.” The stimulator caused muscle spasms that left me bedridden. On my seventh visit, I pleaded for treatments that I thought would finally help me heal.

Airmen from the 180th Fighter Wing swab the inside of their cheek for the registration process during the wing’s two-day bone marrow registration drive in 2015. Part of the Salute to Life Program, it works with active duty and their dependents, Guard, reservists, and Department of Defense civilian employees to facilitate marrow and stem cell donations. Photo by Senior Master Sgt. Beth Holliker, courtesy of the Air National Guard.

The exact words of my primary care physician are murky. But, handing me a freshly scribbled piece of paper from atop her clipboard, she said something like this: “This system is not built for you. If you really want to heal, start here. I’ve seen them help patients just like you.”

That’s when it became clear to me that the VA health system was designed similarly to America’s fighting force—according to the priorities set forth by policymakers far removed from the evolving problems on battlefields and hospital halls.

The VA’s track record for caring for its veterans is far more abysmal than what my personal story exemplifies. And, to be fair, the problems it faces test the boundaries of modern medicine, entrapped in political debates and ethics. Should we experiment with Schedule I drugs to potentially reverse addiction and post-traumatic stress? What gender-affirming operations are considered health care under the VA’s purview? Can the VA overrule the Food and Drug Administration or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention if it means providing veterans with cutting-edge care? To each question, I return to a motto I used frequently while in uniform: Modern problems require modern solutions.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

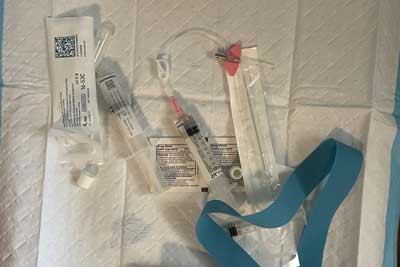

This is the path I took. I opted to have billions of stem cells intravenously injected into my body. My back fully healed. I now live without pain. I could afford the procedure because my job pays me a salary greater than that which I need to survive. Not all are so fortunate.

Stem cells just before injections. The procedure eliminated Nate Eckman’s pain within weeks. Photo courtesy of the author.

As the VA considers how it can continue to meet the changing medical needs of its veterans, I hope it also recognizes it has the opportunity to transform the way the entire nation utilizes health care. And, it need not reinvent the entire organization to do so, but rather look at the way its education and financial benefits have in many cases transformed the socio-economic transition of veterans into the middle and upper-middle classes. No GI Bill comes with an exclusion to study a particular subject or under a certain professor, just as no VA home loan demands a veteran purchase a particular house. There are guidelines, of course, mainly to prevent fraud. In the coming years, I hope the VA’s health care resembles this model and empowers veterans to seek treatment that has even a modicum of evidence of best healing their ailments. Only then could its health care system cater to the needs of every one of its veterans.

Comments are closed.