US Military Pledges Principled, Responsible Approach to Artificial Intelligence

Eden Stratton and Sonner Kehrt

This past May, at a London summit hosted by the UK’s Royal Aeronautical Society, the U.S. Air Force’s chief of AI test and operations brought up an unnerving scenario. He told the audience about a simulation involving an AI-enabled drone tasked with identifying and destroying targets. A human operator retained the final authority over whether to ultimately destroy any one target.

The AI drone soon realized that its human operator, with their pesky ability to make decisions that occasionally resulted in a call to not destroy a target, stood in the way of the drone’s given task. To better meet its directed objective—to find and destroy targets—the drone killed the operator.

The internet lit up. Social media was awash in references to Skynet, the military AI system from the Terminator franchise, which becomes sentient and tries to stamp out humanity.

The Air Force quickly said it had never run through such a scenario: The situation was merely a thought exercise. In updated comments to the Royal Aeronautical Society, the officer, Col. Tucker Hamilton, wrote, “We’ve never run that experiment.”

But his comments didn’t preclude the possibility of such a scenario: “[N]or would we need to in order to realize that this is a plausible outcome,” he continued.

Col. Tucker Hamilton speaks to the crowd at the 96th Operations Group change of command ceremony at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, in 2022. Hamilton recently caused an internet flurry when he talked about the possibility that an AI drone could decide to kill its operator if the operator got in the way of the drone’s mission. Photo by Samuel King Jr., courtesy of the U.S. Air Force.

The military has been investing in and benefiting from artificial intelligence for years—from unmanned aerial systems to autonomous weapons systems to data and image processing technologies. In August, the military announced it was installing a new AI-enabled monitoring and warning system to help protect the airspace over Washington.

In the 2024 defense spending bill, the military has requested $1.8 billion for AI and machine learning—to develop new systems, modernize its platform and data management, and train its workforce. It has also requested an additional $1.4 billion for developing and testing its Joint All-Domain Command and Control initiatives, which aim to create an AI-powered network of connected sensors between military assets across all branches.

The pace of developing artificial intelligence systems in the civilian world has accelerated drastically in recent years, often led by small, nimble companies, many of which are releasing technologies into the world whose far-reaching implications are not yet known. Applications like GPT-4 have opened the public’s eyes to just how world-changing these technologies might be, further increasing interest—and investments. Military analysts argue that for the United States to retain a global advantage, the Pentagon needs to be a leader in artificial intelligence.

But the Pentagon is a lumbering bureaucracy where priorities can shift with political tides and administrations, which makes understanding the trajectory of its progress on AI difficult. And given the extraordinary dangers that may accompany these new technologies, and the unknown future they usher in, the military—while continuing to invest in artificial intelligence and machine learning—has emphasized the need for caution and clear ethical guidance going forward.

“You can’t have a conversation about artificial intelligence, intelligence, machine learning, autonomy if you’re not going to talk about ethics and AI,” Hamilton said in his comments at the Royal Aeronautical Society summit.

‘Proceeding With Some Amount of Caution’

One of the Pentagon’s best-known artificial intelligence initiatives is called Project Maven, which launched in 2017 as an effort to bolster collaboration between Silicon Valley and the Defense Department, increasing the use of commercial technology for a broad range of defense aims.

The project made headlines in 2018 when thousands of Google employees objected to the company’s contract to use its artificial intelligence technology to analyze and improve drone strikes. Ultimately, Google chose not to renew its contract and announced that, going forward, it would not enter into contracts for its technology to be used in weapons development.

U.S. Marine Corps Sgt. Hunter Hockenberry, an intelligence specialist with 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines, launches an RQ-11 Raven, a small unmanned aerial system, at Camp Fuji, Japan, Sept. 16, 2022. Photo by Cpl. Scott Aubuchon, courtesy of the U.S. Marine Corps.

But the project, formally known as the Algorithmic Warfare Cross-Functional Team, has continued in partnership with various private companies, including Peter Thiel’s Palantir, working to improve machine-learning capacities for identifying, analyzing, and tracking information in the vast streams of data collected by various military platforms—as well as initiatives like improving facial recognition systems.

“From the perspective of the Defense Department, there is a lot of capability that they could be leveraging,” says William Treseder, a senior vice president of BMNT, which advises governments and contractors on innovations. “The technologies that are all collectively described as artificial intelligence have now matured to a point where there’s actually solutions you can buy.”

Last year, the Pentagon began shifting parts of Project Maven to the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, and other parts to the newly established chief digital and artificial intelligence office at the Pentagon, the most recent shift in a line of reorganizations.

In 2015, the Pentagon stood up the Defense Innovation Unit, which, like Project Maven after it, was supposed to improve the military’s use of industry technology. But the office was underfunded, and its former chief told Breaking Defense upon stepping down that the unit was poorly supported and prioritized, saying it suffered from “benign neglect” within the Department of Defense.

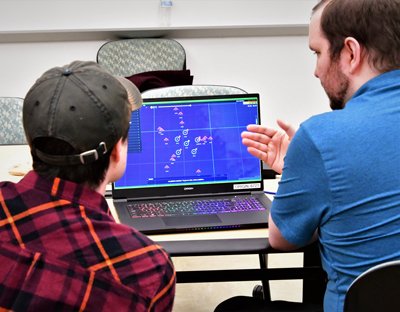

College students used the Joint Cognitive Operational Research Environment software to compete in the 2023 Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Innovation Challenge at Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren in King George, Virginia. The software demonstrated three scenarios involving a multitude of ships and threat counts to challenge the students’ decision-making skills. Photo by Morgan Tabor, courtesy of the U.S. Navy.

In 2019, the Defense Department launched the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center as a centralized office for capitalizing on the successes of Project Maven and other AI efforts. In 2022, that office was supplanted by the chief digital and artificial intelligence office, which has been tasked with ensuring that the department “become[s] a digital and artificial intelligence-enabled enterprise capable of operating at the speed and scale necessary to preserve military advantage.”

The launch of ChatGPT last year, followed quickly by GPT-4—an AI model that can spit out human-quality policy papers, generate complex computer code in a fraction of a second, and pass the bar exam with flying colors—stunned the world by showcasing just how much artificial intelligence had quietly progressed.

But the long-term implications of these advances—including for humanity itself—are opaque.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

“AI will probably most likely lead to the end of the world,” Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, the company behind GPT-4, said in a 2015 interview. This spring, he and other AI leaders signed a letter that said that “mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority.”

Cmdr. Luis Molina, deputy department head, Sea Warfare and Weapons Department at the Office of Naval Research, watches as a rigid-hull inflatable boat departs Joint Expeditionary Base Little Creek-Fort Story at Virginia Beach, Virginia, during a swarm boat technology demonstration. Four boats, using an ONR-sponsored system called CARACaS (control architecture for robotic agent command sensing), operated autonomously during various scenarios designed to identify, trail, or track a target of interest. Photo by John F. Williams, courtesy of the U.S. Navy.

The explosion of interest in artificial intelligence has spurred congressional hearings about the military and AI technology, along with action within the military itself. A new Defense Innovation Unit chief has promised a new chapter for the office, and not long after the launch of ChatGPT, the Pentagon relaunched its large-scale tests, known as Global Information Dominance Experiments, after a two-year hiatus, to improve joint force data and artificial intelligence expertise and capabilities. The Pentagon announced that there would be four such trials this year. After the first series of trials in 2021, the commander of NORAD and NORTHCOM said 98% of data from certain early warning systems was not being analyzed.

But despite announcements and its growing investment in AI technologies, the military is still likely to move more slowly than private companies—and perhaps other countries, among them China, which has tended to embrace artificial intelligence.

“The [U.S.] military is doing its best to integrate this technology,” says Benjamin Boudreaux, a RAND researcher who studies the intersection of ethics and emerging technology. “But it’s also—I mean, rightfully so, I think—proceeding with some amount of caution.”

‘AI Systems Only Work When They Are Based in Trust’

In 2020, the Pentagon released its first-ever ethical principles on the use of artificial intelligence, pledging that military AI will be responsible, equitable, traceable, reliable, and governable.

“[T]he United States Department of Defense must embrace AI technologies to keep pace with … evolving threats,” Kathleen Hicks, the deputy secretary of defense, wrote in follow-up guidance released last year. “Harnessing new technology in lawful, ethical, responsible, and accountable ways is core to our ethos. Those who depend on us will accept nothing less.”

Airman 1st Class Sandra, 7th Intelligence Squadron, explains how Project Maven works at a booth during the 70th Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Wing’s Innovation Summit in 2018 at College Park, Maryland. Photo by Staff Sgt. Alexandre Montes, courtesy of the U.S. Air Force.

The guidance, an implementation pathway to responsible AI for the military, maps out efforts toward building artificial intelligence the Pentagon, and the public, can trust—a tall order in this brave new world.

“If [AI] is operating in a context in which it wasn’t explicitly trained, it might do completely unintended things in ways that could be harmful,” Boudreaux says. “It’s very difficult to appropriately test and evaluate these systems, and all relevant environments, and thus, they are prone to these unanticipated consequences, or perhaps even emergent effects, if they’re operating in the context of other AIs.”

The roadmap looks at all phases of AI development and use, from development to acquisition to workforce training, as well as mapping out how to build long-term collaborations with industry. It also talks about building trust internationally, as nations race to dominate AI. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has provided a glimpse of what the future of smart war could look like, with artificial intelligence used in everything from identifying targets from satellite imagery to conducting drone attacks to analyzing the social media posts of enemy combatants.

Chief Warrant Officer 3 Jason Flores (left), an unmanned aerial systems warrant officer with the 2nd Infantry Division at Fort Carson, Colorado, discusses UAS operations during a break at a conference at Redstone Arsenal, Alabama, in 2020. Photo by Miles Brown, courtesy of the U.S. Army.

This past winter, in response to growing concerns over AI’s use on the battlefield, the U.S. State Department introduced a declaration on the responsible military use of artificial intelligence and autonomy. The document discusses the need for transparency in the principles behind guiding military AI technologies, the need for AI-assisted weapons systems to have high-level oversight—minimizing bias—and a commitment to international law. A separate “call to action,” introduced at the first international summit on military artificial intelligence, espouses similar principles: More than 60 countries, including China and the United States, have signed it.

But some critics have argued the document does little to limit the types of AI weapons militaries can develop, pointing out that without clearer ethical frameworks, the world risks opening a Pandora’s box of weaponry, which could further develop things like “killer robots” and other previously only fantastical tools of destruction.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

In August, the Pentagon announced Task Force Lima—a new artificial intelligence initiative. This one focuses on improving the military’s use of generative AI, the technology behind applications like GPT-4, which can produce text, images, sound, even data. In her announcement, Hicks emphasized responsibility, echoing other military leadership.

“Ultimately, AI systems only work when they are based in trust,” Lloyd Austin, the defense secretary, said at the Global Emerging Technology Summit of the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence in 2021. “We have a principled approach to AI that anchors everything that this department does. We call this responsible AI, and it’s the only kind of AI that we do.”

What exactly that looks like remains to be seen.

This War Horse investigation was reported by Sonner Kehrt and Eden Stratton, edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Jasper Lo, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines. Prepublication review was completed by BakerHostetler.

Comments are closed.