Troops Weigh Leaving Service Over Lack of Care for Kids With Autism Under Tricare

For months, Rachele Adkins shelved suspicions that her second son, Benji, may be autistic. His hazel eyes drifted away from people, and in photos, he didn’t smile. At 20 months old, he still wasn’t speaking. Every child develops differently, she’d tell herself. But in the fall of 2020, a developmental pediatrician at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center confirmed her suspicion, she says. On the drive home, she felt relief—comfort in finally having an answer.

As a major in the Army Judge Advocate General Corps, and in a dual military household (her spouse was also military), she was confident that Tricare, the health care program for active-duty servicemembers, would cover whatever services Benji needed, and that providers wherever she was based would welcome Tricare.

“Never did I expect that it would be a hunt to find a place that will take [Tricare],” she says. “It’s not like some kind of fake, homemade insurer.”

Three years after Benji’s autism diagnosis, little has gone as she expected.

Adkins has had trouble accessing therapy she says is critical to Benji’s growth.

Adkins has had trouble accessing therapy she says is critical to Benji’s growth.

“It breaks my heart because I enlisted when I was 17—in high school—and one of the huge recruiting selling points for the military is our health care,” she says. She’s grateful for Tricare, “but from the special needs community, specifically autism, I feel like [the benefits are] less than Medicaid.”

That’s because Medicaid must, by law, cover autism therapies, including applied behavior analysis, a form of therapy many parents of autistic children consider “the gold standard” for helping their children communicate, learn to independently use the toilet and brush their teeth, and avoid behaviors that can be dangerous, such as running away from their parents. Many advocates in the autistic community disapprove of the therapy, saying the goal is to erase certain behaviors natural to autistic children in favor of behavior deemed more acceptable by neurotypical society.

In the early days of ABA therapy, punishment, rather than rewards, was used to redirect behaviors. Just last year, after a court ruled a school in Massachusetts could continue to rely on electroshock therapy to curb self-harming behaviors in students with developmental disabilities, including autism, the Association of Professional Behavior Analysts put out a statement saying practitioners should use other methods.

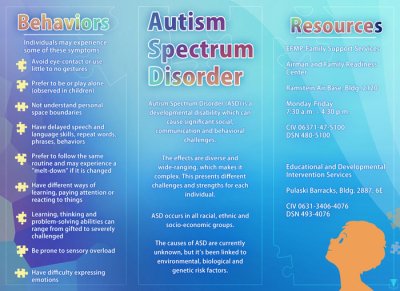

The Air Force put out a graphic to help people understand autism. Illustration by Airman 1st Class Jennifer Gonzales, courtesy of the U.S. Air Force.

All 50 states have passed laws that require state-regulated insurance plans to cover ABA therapy—though each state may differ in how much they cover—and many commercial insurance plans also cover it to some extent. In 2017, the Office of Personnel Management mandated all federal health plans cover ABA.

But the Defense Health Agency has not approved ABA as a full medical benefit because of a lack of rigorous research. So while Tricare has covered autism services since 2001, for the last 10 years, it has covered ABA only as part of a pilot project called the Autism Care Demonstration. The pilot project requires abundant paperwork to track outcomes, as well as guidelines that can change dramatically as the Defense Health Agency evaluates what’s working and what’s not. This will determine what Tricare will ultimately cover as far as ABA therapy.

Wrestling with insurance can cause headaches for civilians and military alike, but some parents say getting ABA under the pilot project causes acute stress and frustration. For instance, much to the ire of many of the 16,500 families in the pilot, in 2021, the Defense Health Agency eliminated ABA-trained technicians who provided therapy in school or community settings, and restricted ABA providers from working on certain activities, like toileting and grooming.

Kirsten Goodson, whose six-year-old son is autistic, is among many parents and providers who want the pilot to end and the ABA autism therapy to become a guaranteed medical benefit. Military life is already hard, and creating barriers for families with special needs children only compounds the strain, she says.

Kirsten Goodson and her son, Theo, pose in the mountains. Photo courtesy of Kirsten Goodson.

“Our families sacrifice so much as it is,” Goodson says. “I want people to know that our disabled children of our warfighters are being treated as ‘less than.’”

In 2022, Mission Alpha Advocacy, a nonprofit advocating on behalf of military parents with autistic kids, surveyed 253 families participating in the pilot program. Ninety percent reported the 2021 reduction in services caused additional depression, stress, or anxiety, and 72% stated they’d leave the military earlier than intended or that they are researching alternative careers.

One military parent wrote, in an anonymous response to the survey, that their spouse once thought of “taking their life” because their life insurance policy would then pay for the several years of services their child needed. Another wrote they were seeking a government civilian job that offered better health care.

“For an organization that touts people first, this whole situation is incredibly disappointing after an otherwise great active-duty career,” the service member wrote.

‘To Me, It’s About Cost’

Autism spectrum disorder, often referred to simply as autism, is a neurological and developmental disorder that affects how people socialize, communicate, learn, and behave. Its symptoms may be mild or may include a spectrum of increasingly severe symptoms. An estimated one in 36 children in the United States lives with autism, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—up from 1 in 44 in 2018. In the United States, boys are nearly four times more likely to be diagnosed with autism than girls.

Research hasn’t determined what causes autism spectrum disorder, and there’s no definitive cure, though a range of therapies can help, including ABA. The therapy involves analyzing how an individual behaves in different environments. A behavior analyst helps figure out how to modify negative behavior when it erupts using rewards and repeated redirection. For instance, an ABA therapist finally got Goodson’s son to brush his teeth by finding a visual prompt he responded to—a timer that started at just 10 seconds, but slowly increased Benji’s total brushing time—and providing a reward of his iPad or favorite Lightning McQueen toy car at the end. The therapy, which can add up to 40 hours per week and last months or years, is personalized to each child’s needs.

More than 35,000 active-duty and nonactive-duty family members have an autism diagnosis, according to a spokesperson for the Defense Health Agency, and a little less than half receive ABA therapy through the pilot program. But participation grew 44% between 2015 and 2021, and the total costs of the pilot program increased by 166% over that same period.

Though ABA is considered an effective treatment by the U.S. Surgeon General, the American Psychological Association, and other medical associations, the Defense Health Agency isn’t yet convinced that enough evidence exists to consider it a gold standard. Goals for the pilot program include understanding how many hours of ABA therapy create measurable improvements, how other treatments—like occupational or speech therapy—can complement ABA, and if parents can play a bigger role in behavior redirection.

For ABA advocates, this pilot feels a lot like the Defense Health Agency trying to pinch pennies around autism care: One hour of ABA therapy can cost about $82 per hour, and it’s not uncommon for autistic children to receive anywhere from 10 to 40 hours of therapy per week.

“To me, pretty clearly, it’s about cost,” says Gina Green, a board-certified behavior analyst and former CEO of the Association of Professional Behavior Analysts. “I think what they don’t look at is, long term, if people with autism get effective services while they’re young, or really at any point, there’s evidence that that’s going to save money in the long run, because they’re not going to need as much help. They’re not going to need as [much] specialized health care and other services later on.”

Kayleigh Norton, applied behavior analysis therapist, reviews numbers with six-year-old Carl, son of Sarah and Tech. Sgt. Carl Sole, 628th Security Forces Squadron flight chief, in 2012. ABA therapy uses specific techniques and interventions to help children with autism or other special needs succeed. Photo by Airman 1st Class Dennis Sloan, courtesy of the U.S. Air Force.

In reports to Congress, the Defense Department states that younger beneficiaries have shown more improvement of symptoms than older ones in the pilot program, though a majority have shown only modest improvement, and a small fraction of participants have experienced worsening symptoms. Green says the way the Defense Health Agency measures outcomes is flawed and does not accurately capture the effects of ABA interventions on areas of functioning that are affected by autism.

Air Force Col. Eric Flake, a pediatrician and founder of the Joint Base Lewis McChord Center for Autism Resources Education and Services in Washington state, says autism is a complex disorder. He understands why military parents may want to scrap the pilot program and have ABA as a full medical benefit. But the pilot’s ongoing research may help uncover a reliably efficient, successful blend of therapies that could ultimately benefit both military and civilian families alike, he says. With that as the goal, ending the pilot now would be premature.

“I think it’s appropriate to keep [the pilot] where it’s at,” he says.

It’s not just military families who have advocated for an end to the pilot program: In November 2022, a bipartisan coalition of 11 House representatives urged the Defense Health Agency to make ABA a “standard, basic Tricare benefit consistent with benefits contained in all other federally sponsored health benefits and insurance programs and eliminate the significant burdens the [pilot program] currently imposes on military families.”

In a response letter this spring, Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness Gilbert Cisneros stood firm, writing that DHA continues to review ABA research, but so far there are “well-documented research gaps” about the effectiveness of it. He said the research had small sample sizes, and there is “an overall low quality” of existing studies. Comprehensive ABA therapy is popular in North America but, according to a recent paper, is rarely used in Europe because providers believe it is not evidence based.

The pilot program was slated to end in December 2023, but the Defense Health Agency extended it, for the third time, through 2028 at a cost of $3.8 billion.

‘I Felt So Deflated’

Lindsey Gandy learned Tricare was cutting her son’s autism services when her husband, a captain in the Air Force, was deployed to Afghanistan in preparation for the pullout of American forces. It was the spring of 2021, and the Defense Health Agency announced they would no longer cover ABA services in educational settings.

“I felt so deflated,” Gandy recalls. Her son, Kingston, who is now 12, had been attending a year-round school that folded ABA services into the day. Kingston, who couldn’t sit for three seconds in a classroom before attending this school, had started to make progress.

According to a Defense Health Agency spokesperson, services in schools and other community settings, like doctor’s offices—an often difficult place for autistic kids to navigate—“have never been authorized under the [pilot program].” But it wasn’t until 2021 that the Defense Health Agency realized those services were being reimbursed and took steps to “close the administrative gap.”

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

At first, Gandy thought Kingston’s school had found a solution: separating the classrooms and the rooms where targeted ABA therapy occurred. But a few months later, Tricare cracked down and would not approve of that arrangement, either. Gandy says the school’s director ultimately decided to stop taking Tricare kids.

Gandy panicked. And the following morning she started calling ABA providers near Hill Air Force Base in Utah, where her family lived.

“There were eight other ABA companies,” she says. “I called every single one of them. They said that they’re either cutting their Tricare patients loose or, when they move, they’re not taking any more. Or, ‘We can’t afford to take Tricare patients,’ so they’re not accepting them anymore. And I was like, ‘Oh, now what do we do?’”

In the first quarter of 2022, 654 behavior analysts terminated their contracts with Tricare, including 13 in Utah—triple the rate of contracts terminated from the first quarter in the previous year. In data provided to The War Horse for years 2021 and 2022, most quarters see a net gain of providers coming into the Tricare network even if hundreds terminate contracts.

A Defense Health Agency spokesperson, Peter Graves, says the agency knows about the complaints from parents who say providers will not accept new patients. Sometimes, that’s because a family may prefer a provider who is fully booked, rather than connecting with one who has openings, he says.

In 2021, the pilot program added Autism Care Navigators to help parents through such hurdles. But only beneficiaries added to the program beginning in the fall of 2021 qualified, and Gandy did not make the cut.

She and her husband ultimately decided to buy additional health insurance coverage through Utah’s health care marketplace, and then again when they moved to Alaska this summer. They pay $440 per month, and every day, when Kingston goes for services, Gandy owes a $35 copay.

But in Alaska, state-funded plans must cover ABA in school settings—exactly what Gandy thinks will help Kingston become more independent and able to maneuver neurotypical society.

“It’s expensive, but he’s getting exactly what he needs,” says Gandy, adding that she’d like to see more collaboration between the Defense Health Agency and military families advocating for ABA. “I think that if DHA was truly concerned about their service members and their dependents’ well being and health, that they would be more open to reevaluating all of this.”

‘It’s Not a Rare Condition. It’s Autism’

Unlike civilians—who, once they find good services for their special needs child, stick with them—military life requires frequent moves. The Exceptional Family Member Program supports military family members with special medical and education needs, and that includes making sure families have services before they move to a new duty station. A Defense Department inspector general report released in August found that some of the program’s offices are low on staff and lack sufficient oversight and data collection, which means families move to installations without the services their family members need.

When The War Horse first talked with Adkins in July, she had just moved to Washington from Colorado Springs a month earlier. In Colorado, Benji, who is now four, had made great strides while receiving ABA therapy, she says. He had learned his letters and could speak several simple phrases, such as, “Juice, please.”

He is a “happier kid because he has the ability to tell us what he wants,” Adkins says.

But in the nation’s capital, he had been without services for more than a month, and Adkins feared he was regressing. She had to switch from Tricare West to Tricare East, and though she started the process before she left Colorado, she still didn’t have Benji’s new authorization for ABA. And although her move was approved by the Exceptional Family Member Program, she couldn’t find an ABA provider who would accept a new Tricare patient.

“It’s not like some very rare cancer or rare heart condition, you know?” she says. “It’s autism. When you are hearing that large locations such as D.C. don’t have care, I mean, where the heck does?”

In 2022, the Defense Health Agency reported that, across all states, the average wait time from the referral date to the first ABA appointment ranged from zero days to 56 days. Pilot program participants in 36 states and D.C. got their first ABA appointment within Tricare’s 28-day access standard for specialty care, according to the report, but that wasn’t Adkins’ experience.

Dr. Kristi Cabiao and her son, Logan, sit together on an airplane. Photo courtesy of Kristi Cabiao.

Kristi Cabiao hears stories like Adkins’ frequently. The family doctor and military spouse, who has a seven-year-old with autism, started Mission Alpha Advocacy after Tricare’s 2021 changes to ABA coverage.

Parents often come to Cabiao with hardships, such as trouble following the pilot program’s requirement that kids get reauthorized for services every two years, or treatment plans denied by Tricare because they include therapy around daily living skills.

A Defense Health Agency spokesperson says an inability to groom oneself or complete chores are not “core deficits” of autism, and so families should help guide or manage those behaviors.

When Cabiao’s son, Logan, could no longer have an ABA specialist tag along on trips to the store, park, or dentist, his behavior in public settings regressed to the point that Cabiao had to leave Logan at home, rather than risk him running away or plucking an apple from the grocery display for the visual stimulus of watching apples cascading to the floor.

She also noticed that when the ABA provider tried to work with Logan on tolerating medical and dental exams in their clinic, he’d “do great, but as as soon as we changed the setting to the medical office to practice, he would become afraid and wouldn’t tolerate an exam,” Cabiao says, adding that she now relies on Ativan to calm him before appointments.

Parents, including Cabiao, also bristle at the pilot program’s mandatory parent stress surveys, implemented in 2021. The surveys, required every six months, include requests for information that some feel are intrusive, such as reporting problems within marital relationships or if their child’s behavior disappoints them. The surveys are meant to help support parents and to offer relief through respite care. And Cabiao says the intent is fine, but it feels “manipulative” to tie ABA services to surveys parents may not feel comfortable taking.

Her family’s challenges with the pilot program contributed to her husband’s decision to leave the Air Force this year after 21 years in service, Cabiao says. The pilot project could “continue to become more and more restrictive, and have more and more hoops to jump through.” Though she and her husband have enjoyed military life, she says Logan’s care outweighed any reasons to remain on active duty.

‘It’s the Hardest Program to Work With’

In the 2022 survey conducted by Mission Alpha Advocacy, more than 80% of 247 ABA providers surveyed said that, when compared to other insurance and health care plans, Tricare requires the most paperwork and nonbillable requirements to get paid. A little more than half said Tricare is unusually slow at reimbursement.

One agency in South Carolina anonymously stated Tricare is a “nightmare” to work with and not worth the stress and time associated with denials and resubmittals of treatment plans. In reports to Congress, the Defense Health Agency frequently mentions concerns over fraud within the pilot program, including services billed to Tricare that were never rendered and falsifications of care. A 2017 inspector general report brought the problem to light.

“This is not the easiest program—in fact, it’s the hardest program to work with because it has more expectations,” says Kari White, the clinical director of Mariposa Behavioral Health Services, an ABA provider that serves families based at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. “They’re not the fastest payer and they’re not the highest paying.”

On top of that, some providers say the 2021 changes limiting where and how much ABA therapy is covered has made it difficult to help kids “across all aspects of their development,” in essence creating barriers to success at their jobs, says Jenne Nesbitt-Decker, the owner of Mariposa Behavioral Health Services.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

But Flake says there are “three different pillars of services” when it comes to caring for autism, and they can come from medical care, community resources, and support in schools. With that in mind, he says, Tricare should not be on the hook for all treatment in all settings. And perhaps the pilot program may better sort out what care belongs under each pillar, he says.

The 2022 defense bill requires the secretary of defense to have the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine conduct an analysis of the effectiveness of the pilot program. The study will likely be completed next year, a Defense Health Agency spokesperson says.

After two months without services, Adkins’ son Benji was authorized for ABA services toward the end of summer. She says the only provider who had space for her son and accepted Tricare could take him for only 30 hours a week, even though his pediatrician had authorized 40 hours.

“That means I’m working from 9:30 to 2:30,” she says, “which is not exactly Army hours.”

Though her coworkers have been understanding, she’s struggling to find a long-term solution. Her husband studies at the National War College, most daycares won’t accept Benji because of his special needs, and finding a nanny who will care for a largely nonverbal autistic six-year-old—including diaper changes—is difficult. Though she had occasionally thought about leaving active duty to become a private attorney with private insurance, the move to D.C. has been “the straw that broke the camel’s back,” she says.

As a mother, of course, Adkins wants what is best for her young son. As an Army officer, she always envisioned staying in “as long as the Army wants me.”

This War Horse investigation was reported by Anne Marshall-Chalmers, edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Headlines are by Abbie Bennett.

Comments are closed.