The Shoulders I Stood on Were Gone. How Little I Knew of the Journey Before Me.

A Delta Force unit zipped over the barren desert. Two Black Hawks contained assault forces. Four Little Birds carried riders and artillery. It was a perfect blue sky in Taji, Iraq. The operators stalked a high-profile target. All went according to plan until it didn’t.

The date was Nov. 27, 2006. For the first time in his seasoned career, the flight lead heard “Mayday, Mayday, Mayday!” over the radio.

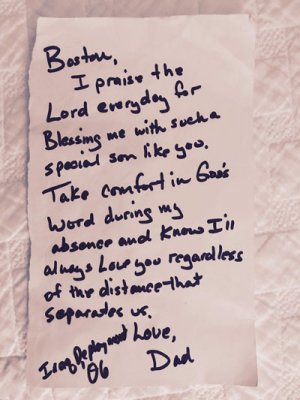

A note from Air Force Maj. Troy Gilbert to his son, Boston, before he deployed to Iraq in 2006. Photo courtesy of the author.

Meanwhile, I was sound asleep in the bedroom I shared with my little brother. We lived in a small but comfortable home in scorching Phoenix. The morning commenced with what I expected to be a normal day at Corte Sierra Elementary School. Abnormal for a school night, my mom told us we would sleep over at a friend’s house that evening. Even my fourth-grade sensitivities knew something was off.

I missed my dad. He deployed two months prior and was set to return just after Christmas. I missed the smell of his Barbasol shaving cream lather. I missed him steering with his knees, convincing me the wheel of his 1992 Chevy Silverado moved by magic. We listened to ’80s rock because, according to him, that was “real music.”

Boom! An unidentified projectile removed the tail rotor from one of the Little Birds. An 80-mile-per-hour crash landing ensued. It was not long before the shooter showed himself. Moving with intent, five weaponized trucks housing dozens of al-Qaida affiliates traversed the flat earth. Heavy machine guns with long-range capabilities enabled the trucks to fire first. The operators dug in the sand for cover as rounds cracked like fireworks.

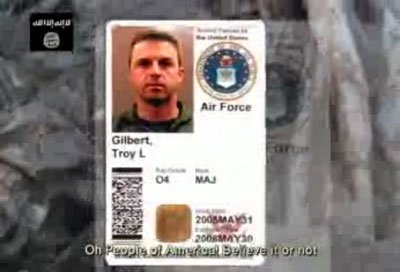

Al Qaeda insurgents took the body of Air Force Maj. Troy Gilbert from the wreckage of his F-16 before U.S. forces could arrive. This screengrab is from a propaganda video that included footage from the crash site. Photo courtesy of the author.

My dad was skybound. Perched in his F-16 viper, he showed restraint during an air-to-air refuel as a call for air support pierced the radio. At 100 shots per second, his 20 mm Gatling guns devastated the lead trucks after he rolled off the tanker. A tight turn to initiate his subsequent attack dropped him 200 feet from the deck. He was pushing the edge of aviation and he knew it. After scattering the remaining enemy forces in a final act of fire, 500 miles per hour met the brutal fact of the desert floor.

Major Troy “Trojan” Gilbert died with his nose to the grindstone.

My friend’s mother drove us to our home rather than to school the following morning. She was quiet. The front door opened, revealing my grandparents, friends, and other family members encircling the couch where my mom sat somberly. After hearing the unhearable, I retreated to the bathroom for solitude. I was nine. Dad was gone. I couldn’t believe it.

“When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves,” wrote neurologist, psychiatrist, and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl.

I wanted my physical father, but I could not have him. From that moment on I was left with the tremendous task of filling the void he left. Symbolically speaking, his passing represented disintegration and chaos in my world. My role model father, the impetus for my life and the shoulders I stood on, was gone. How little I knew of the pilgrimage set before me. How little I knew of the question entangled in my journey: How can I make meaning from my loss?

The dignified transfer of Air Force Maj. Troy Gilbert. A 29-person team consisting of several members of Task Force 160, the unit that he died protecting, retrieved his body and escorted him home. Photo by Senior Airman Aaron J. Jenne, courtesy of the U.S. Air Force.

Parts from my dad’s jet lay strewn across a carrot field. Prior to the arrival of U.S. forces at the crash site, insurgents filmed the scene and took his body from the wreckage. He was lying prostrate on a plastic sheet as smoke billowed in the background. They titled the propaganda video “The Missing.” We buried an empty casket. Ten years passed before his recovery and homecoming.

I fondly remember my dad taking my mom, brother, and me to watch Star Wars: Episode III in the theater. He waxed poetic about collecting Marvel’s early Star Wars comic books and watching the originals as a kid. It wasn’t until years later that I understood the profound connection linking me and the protagonist of the original trilogy. Luke Skywalker tells his companions he wished he had known his father. Central to Luke’s destiny is discovering the truth about his father.

Air Force Maj. Troy Gilbert with his sons. Gilbert was killed in Iraq in November 2006 while protecting U.S. troops. Photo courtesy of the author.

A hero from a war bearing my dad’s callsign also went missing. The Odyssey contains a much older example of the archetypal father quest found in Star Wars. Reeling from his father’s absence, King Odysseus’ son Telemachus is in turmoil. Immature, victimized, and disoriented, Telemachus is an embittered bystander as suitors take advantage of the vacant throne on his home island of Ithaca. They ravage his kingdom and harass his mother.

I puked on the flight back from the funeral. Was it the stress? The attention? Was I purging the tumultuous two weeks leading up to the service? I was just a boy when I gazed upon his white marble headstone for the first time. Little did I know his death marked my separation from childhood and my entry into a liminal space.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

It is not a coincidence that I found soccer soon after losing my father. The unpredictability and finality of his death proved to be fertile soil for the game to sprout as my primary identity. Budding as an athlete, soccer promised security, validation, and self-worth. Like Telemachus, who tells Athena, “Mother has always told me I’m his son, it’s true, but I am not so certain,” I was unsure who I was. Seeking individuation through soccer, I was subject to the instability of its every whim.

The decade between my father’s death, confiscation, and return saw an eclectic array of service members hunt for his remains: SEALS, Green Berets, intel analysts, search dogs, and Marines chased the ghost. Their first discovery catapulted me back to Arlington National Cemetery for a second burial seven years after the first. A small box of toe bone fragments was laid on his casket.

“It is not a coincidence that I found soccer soon after losing my father,” writes Boston Gilbert. “Budding as an athlete, soccer promised security, validation, and self-worth.” Photo courtesy of the author.

Three years later, a tribal chieftain local to Fallujah disclosed the whereabouts of my father’s full remains. A 29-person team consisting of several members of Task Force 160, the unit that he died protecting, retrieved his body and escorted him home.

It is not a coincidence that I lost soccer soon after finding my father.

I underwent consecutive foot surgeries during my sophomore season of college soccer, only nine months after my father’s homecoming. Soccer as my chief identity was a house of cards, and it fell hard. The psychospiritual challenges that afflicted me during my two-year-long recovery resembled the struggles of my fabled forerunners from Ithaca and Tatooine. Ancient Greeks would have understood this juncture in my life as a kairos (καιρός): a word they used to describe the right, critical, or opportune moment for action.

Luke Skywalker’s lowest moment is when the tyrannical Darth Vader reveals himself as Luke’s father. For Telemachus, it is his depression at the suitors’ exploitation of his home and his mother, and his inability to do anything about it. Each character’s kairos was essential to the formation of their character and the discovery of their identity.

My kairos led to a personal revelation in a movie theater with my then-girlfriend and now-wife. Fans of the original Lion King, we spent a night out watching the digital remake. After grappling with the death of his father and evading his destiny, Simba has an encounter that changes the course of his life. The pride’s mandrill shaman, Rafiki, facilitates a communion between Simba and his father, Mufasa, who reveals himself as a ghost in the sky. In desperation, Simba pleads, “Don’t leave me again.” Mufasa’s response gripped me through the screen.

The empty casket of Air Force Maj. Troy Gilbert is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Photo courtesy of the author.

“I never left you. I never will. Remember who you are.”

To this, Rafiki questions Simba, “And so, I ask again. … Who are you?”

Without reservation, Simba replies, “I am Simba, son of Mufasa.”

A tear slipped my guard and quietly rolled down my cheek. It clicked. I know who I am.

I am Boston, son of Troy. Nothing can take that away from me.

In all three epic stories, the sons return where they started: basking in the simplicity of their secure identity as beloved sons of their fathers. Telemachus and Odysseus are reunited and slay the suitors. Luke Skywalker redeems Darth Vader by turning him from the Dark Side and reinstating him properly as Anakin Skywalker once again. Simba heeds Mufasa’s call to reclaim his right as the one true king of the Pride Lands.

Renowned poet T.S. Eliot writes:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

Although I can never bring my dad back, I am invigorated by the prospect of making him come alive by accepting my unshaken identity as his son, boldly embracing the challenges in my life like he did, and living as well as I know how. In doing so, I gain an immense sense of myself through remembering and relating to him.

I would alter Frankl’s quote: “When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to know ourselves.”

Even in death, my father beckons me to uncover my unique personhood.

Comments are closed.