This Story Is More Than a Revelation of Why I Hated Christmas

For the longest time, I didn’t look forward to the holidays the way a dad of three ought to. I once thought it was because I was raised on little extravagance, especially with respect to Christmas and gifts in general.

But after an evening in which I became violent—an incident that left a sliding glass door, a scotch glass, a cooler, and a shirt worse for wear—I knew I had to look in the mirror and try to understand where that person came from and why. Why did I act this way, especially this time of year?

For decades, I rarely looked back. Now it was time.

Raub Nash joined the Oklahoma National Guard in 1999. A few years later, he was at war. Photo courtesy of the author.

Dec. 21, 2004. Four days before Christmas. A pristine day in Mosul, Iraq, with clear skies and mild temperatures. I am a young second lieutenant platoon leader assigned to the 1st Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment. After two months in country, I’ve finally settled into a routine—normalcy but not complacency.

Our platoon has experienced our share of “baptism by fire” incidents, and we are operating as a cohesive unit for the first time. A routine patrol day starts with the usual events—drive up to our platoon area, search houses/garages/offices, chase people who ran from our patrol, and drive back.

By the time we return to the forward operating base, it is time for lunch. So we drop our gear for the long walk to our chow hall. Before we head out, our commander and a few other officers ask my platoon sergeant and me to go with them to lunch. We decline; we need to help close up our vehicles and let our soldiers get to chow before us. The routine is almost always the same—clear your weapon and wash your hands outside, get a tray and choose between the main or short order line, get salad and dessert in the middle of the chow hall, sit down to eat and talk about whatever comes to mind, then clean up and leave.

But this day will deviate drastically from that routine.

About the time I sit down, I look up and see the three others I usually sit with heading over. I give an obligatory wave of the hand for them to join me. As my platoon sergeant sits in front of me, I see a flash of light and hear a loud boom that shocks our world.

The routine I have settled into includes reacting to the occasional mortar attack, and I do what almost everyone else does—jump up, look for those nearby, and run to a bunker just outside.

I won’t write anymore about what happened next. It is an image and an event I want to keep buried. But the result of the event was my first experience of losing a comrade. My commander, Capt. Bill Jacobsen, and Staff Sgt. Robert Johnson, our noncommissioned officer responsible for nuclear, biological, and chemical operations, died while they ate lunch in the safety of their forward operating base. Twenty-two people died that day, but these were the ones I knew.

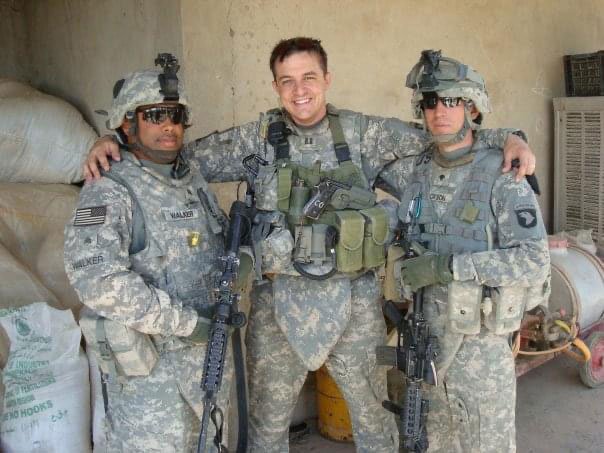

Raub Nash, center, wondered for years why he dreaded the holidays. Turned out he never fully reflected on the awful events he experienced around this time of year. Photo courtesy of the author.

Eight days later. Dec. 29, 2004. Our platoon responds to a suicide bomber who drove a dump truck full of explosives precariously close to an outpost and denonated the device. Pfc. Oscar Sanchez dies in the blast. But what most people don’t know is that he probably saved the lives of his entire platoon. If the truck had made it another 100 feet or so, the entire building almost certainly would have collapsed.

I recall this event not because of the incident itself, but because of my actions. Several times, I felt forced to place my platoon sergeant and squad leader in danger. When I say forced, I mean it. I did not like the orders I got, but a leader understands that sometimes orders must be followed and that people can get hurt following them.

What scares me most, though, is how happy I felt when I saw things get destroyed in the ensuing firefight. I felt joy as we engaged the suspected—yes, suspected—targets with heavy machine guns and strafes from F-16s and the now-retired F-14.

I don’t know why I felt this way, but I suspect it was because I was in the early stages of burying the emotional destruction that had come from the chow hall bombing.

Jan. 22, 2005. A good friend, someone I looked up to, 1st Lt. Nainoa Hoe, is killed by a sniper in Mosul across the river from us. The news hits me hard. Less than a month later, on Feb. 19, 2005, Spc. Clint Gertson is killed in another random shooting while on patrol. We called Clint “Big Country,” and he was a light in our company amid the darkness.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

Dec. 20, 2007. Almost three years to the day since the lunchtime bombing that killed my commander and our chemical operations specialist. I am a young company commander in the 101st. We’re finishing up an operation my soldiers have aptly dubbed “Operation Shitty Christmas.”

Much like the outpost bombing, I don’t agree with or understand what we’re trying to accomplish. But the orders are legal, ethical, and moral, and I have had ample time to object and add my spin to the operations, so we execute.

After five days in the middle of nowhere during an unusually cold spell, we trudge away at the impossible goal of finding a nonexistent enemy. The day is just like any other, except that we’ve finished the mission and we’re moving back to our base.

After many difficult Christmases, Raub Nash looked in the mirror and learned who he was and why. Photo courtesy of the author.

One of my platoon is tasked with following a route clearance team on an untraveled route to open it for our sister company. I move with my main effort to get all our equipment safely back to our company patrol base. The decision still haunts me.

Cpl. Wesley Leon-Barrientos was the first person I met after I arrived at Fort Campbell and learned what company I would command. He was youthful-looking but had an air of experience, and I was immediately drawn to him. I’d look for him during formations, physical training, and out training. As I got to know other soldiers in the company, I learned Leon was a warrior. I liked him, and I knew I could always count on him.

On this day, Leon is in the patrol that goes with the route clearance team, most likely located in the order of the march where my vehicle should be. His vehicle is hit by an improvised explosive device. He loses both of his legs

He is in a high mobility multipurpose wheeled vehicle—a HMMWV—that offers little protection against the blast. I am in a mine-resistant ambush-protected vehicle, or MRAP.

I already struggled with empathy. After Leon’s injury, I separated myself from my feelings more than ever. I resolved to never get close to another soldier.

It was a terrible decision. No wonder I am a Scrooge when December rolls around.

But this story is much more to me than a revelation of why I hate the Christmas season. It is a cathartic view of how people need to—and should—reflect on everything that happens to them that is outside of their control.

Raub Nash with his three sons. Photo courtesy of the author.

I wish more people would participate in this exercise and look at their own actions and reactions to trauma. I know now why I feel the way I do. And knowing this is what allows me to accomplish my ultimate goal—being a great dad.

Nothing gives me greater joy than seeing my sons smile. I don’t want to allow what happened to me to affect them. I don’t want them to dread Christmas the way I do.

It is 2023—the holiday season. The exercise of looking in the mirror, of learning who I am and why, was hard. But it was healing. By reflecting on these major events and others from my time in service, I now make it a standard activity when I am faced with hard choices and feelings.

Since putting these experiences on paper more than a decade ago, I have taught my three sons the value of reflection. I can see it in their lives—the way they have weathered their own challenges and recovered from painful events.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

What happened in Iraq didn’t and won’t define me. But coming to terms with it has made me a better and more empathetic person. I believe we all have the power to take our trauma and mold it into something better.

My experiences—and these are just a few of them—are not unique among those who served in the forever wars. It scares me to think how little I understood how they’d changed me, for better and for worse.

Christmas isn’t so bad anymore. In fact, I am looking forward to it.

This War Horse reflection was written by Raub Nash, edited by Kristin Davis, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.