António Guterres’ UN: A story of missed chances and diplomatic flops

In the days leading up to Lynn Hastings’ departure from UNESCO, we’re reminded once again of the world’s imperfections. Hastings, serving as the deputy to the UN Secretary-General‘s Special Coordinator for the Peace Process, Tor Wennesland, and as an envoy for humanitarian affairs, faced visa denial by Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs following her criticism of an Israel Defense Forces (IDF) operation in Gaza.

We’re witnessing a global reality marred by wars and crises, overseen by governments helmed by egocentric figures more concerned with their social media following and public adoration than the actual fulfillment of their duties and effective policy implementation.

Sadly, this global trend also affects the UN. Tasked with overseeing the broader picture, the UN is plagued by biases and limitations. Its failures span multiple crises – ISIS in Iraq, genocide in Syria, the Yemen war, and the recent conflict with Hamas. In each, the UN’s bias has been notably negative.

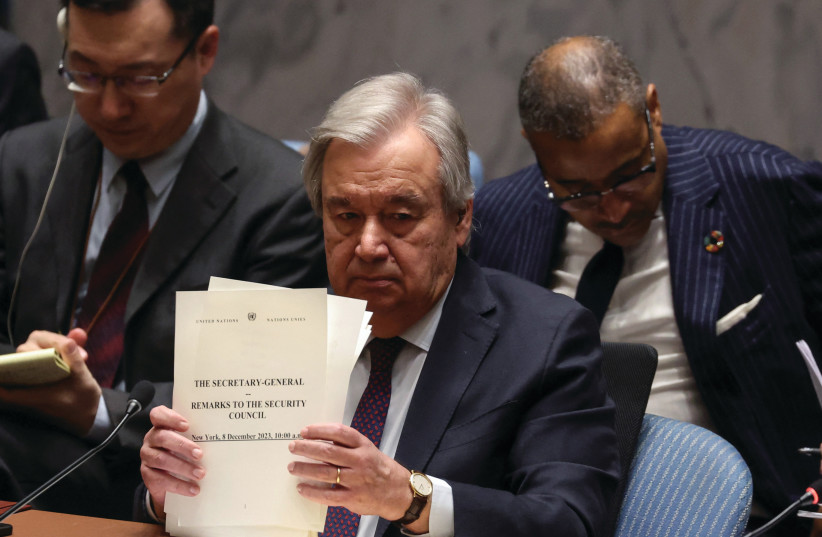

During António Guterres’ tenure as Secretary-General, the UN’s leadership has been notably absent in critical times. For instance, they remained passive during the Saudi-led bombing of residential areas in Yemen and the Syrian regime’s mass atrocities, with Russian and Iranian support.

In Iraq, the UN’s representatives barely grasped the complex political and security landscape of Baghdad. Conversely, in the Cypriot crisis, Guterres attempted to be proactive, involving the current Norwegian Foreign Minister, but ultimately failed. Even Libyan Khalifa Haftar rejected Guterres’ meeting proposal.

Recently, another Norwegian diplomat, Tor Wennesland, found himself entangled in the complexities of the Gaza Strip. Struggling to find his voice and set a clear agenda, his office barely stays afloat thanks to a few competent staff.

Guterres handling of other crises

In the Ukraine crisis, as in Gaza, the UN, under Guterres, quickly labeled the situation a “humanitarian crisis,” overlooking the deeper causes and implications. The question arises: does Guterres view leaders like Putin as lawbreakers or as perpetrators deserving of trial for massacres?

Guterres delegated his authority to Martin Griffiths, his deputy for humanitarian affairs and emergency aid coordination. Griffiths hastily framed the Gaza crisis as a humanitarian disaster, with both he and Guterres drawing hasty conclusions without fully understanding the crisis’s genesis.

Regarding Hastings, she epitomizes the issues outlined above and represents what’s wrong with the UN’s approach. She seems to believe that media appearances can alleviate the suffering in Gaza or console the families of the kidnapped. Hastings, like other UN agencies and the Secretary-General himself, doesn’t appear to seek truth or understand the terror experienced by Israel and its society.

Israel is introspectively assessing its current situation, and it’s only a matter of time before the implications become clear. Many politicians, now frequently seen in the media, may not have a long tenure, as Israeli society is unlikely to forgive them.

Hastings, not being indispensable, was rightly asked to leave. Her approach, more political than diplomatic, has overshadowed her professional responsibilities. However, other UN envoys, more upright and professional than her, manage to perform their duties effectively despite occasionally challenging Israeli policies.

Comments are closed.