They Were Worried About the Color of Our Bras. We Were Busy Spearheading Change.

“Lt. Van, see Maj. Shire after class,” directed the instructor.

Uh-oh, I thought. It’s never good to be singled out, especially when you’re a student at a military school like Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi.

As the Navy equivalent to an Air Force captain, I was the senior person in the Air Force’s Introduction to Data Processing Course Class 78, but I held the opposite position in academic standing. Learning how to program in COBOL and assembly language was kicking my butt. My classmates were first-tour officers, younger (22 to my 26), and had studied computer science in college, which was just becoming mainstream in 1983.

Capt. R. Van with her uncle after she was commissioned into the Navy. Photo courtesy of the author.

When class ended, my classmates asked what was going on. I shook my head and ran up the stairs to the staff floor.

The brass plaque on the door read: Major S. I. Shire, USAF, Squadron Commander.

A third of the way into this three-month course, I still couldn’t decode the slew of Air Force acronyms that followed his title. Shire was responsible for the computer systems program and its cadre of instructors, as well as the hundred or so students cycling through the curriculum. I was the sole khaki dot in a sky of Air Force blue.

I knocked on the door and entered at the man’s greeting. I was struck by the room’s disarray, which was noticeably worse than when I checked in with him a month before. The office was sparsely furnished but still managed to look cluttered. A stock Air Force poster of an F-15 Eagle tactical fighter jet zooming through the clouds, its paper ends curling with age, hung behind a metal desk. A bookcase, bursting with black binders and stacks of computer punch cards and printouts, tilted by a ratty couch.

“Maj. Shire, you wanted to see me?” I didn’t salute but stood in front of the desk, not sure of the protocol for this kind of meeting.

A box by the desk contained the iconic ramen noodles and cans of soup of those living alone. A brown-tipped spider plant in a Piggly Wiggly yogurt container tried to grow, despite being on the windowsill above a radiator.

“Sure, Lt. Van, take a seat.” He pointed to the lone gray metal chair with books stacked on it across from the desk. “Put those on the floor. How’s the course?”

“Well, it’s a challenge but doable, sir,” I said.

He nodded. “Good. We don’t get many Navy types here. Right. So. There’s a problem in your class.”

“What is it, sir?” The students were well-mannered, nearly catatonic by Navy standards. Everyone seemed to get along. The top student was Air Force 2nd Lt. Davenport, a svelte Black woman we nicknamed “Star” because of her technical acumen. She helped me decode the gobbledygook instructor-speak that would otherwise be over my head.

In 1974, the U.S. Navy designated its first female naval aviators, four of whom posed for a photograph during their flight instruction. Pictured left to right are Ensign Rosemary Conaster, Ensign Jane Skiles, Lt. (junior grade) Barbara Allen, and Lt. (junior grade) Judith Neuffer. Allen, the first to receive her wings, was killed in a training accident in 1982. The other three officers pictured eventually retired as captains. Photo courtesy of the Naval History and Heritage Command.

“It’s a matter that requires a measure of delicacy.” He twirled a glossy blue Montblanc pen. “It seems that one of the students is consistently out of uniform.”

“Tell him to get with the program,” I shrugged.

“It’s not a he; it’s a she,” he said. “The officer in question is a female.”

“Then tell her—”

He coughed politely. “We can’t really do that, Van. It’s your job.”

“Major, I’m missing class time that I can’t spare. Tell me in simple terms that even a sailor can understand what the problem is and what you want me to do about it.”

“You’d better close the door.”

I hadn’t heard of any disciplinary infractions among my cohort. I’d seen unsavory behavior after two Navy tours—heck, some of it was my own—so nefarious acts of all sorts flew through my head, from drunk and disorderly to murder. What could warrant this attention?

“It’s about … a … brassiere,” he choked out. “Second Lt. Davenport wears … a black one.”

“You called me in to discuss underwear?” I didn’t even try to keep a straight face.

He put both hands on the desk and leaned forward as if to share a secret. “You must take this seriously. She wears a black … brassiere.”

“And I wear a white one. And they’re called bras, Major. At least since, oh, the 1930s.”

Shire’s face was crimson. “That’s it, she wears a black—one—and it shows through her uniform. The light blue material.”

What was he saying? Women were less than 10% of the military. Everything about “those girls” was new. Regulations for women’s uniforms were ignored or foisted on the nearest woman to handle. Like now.

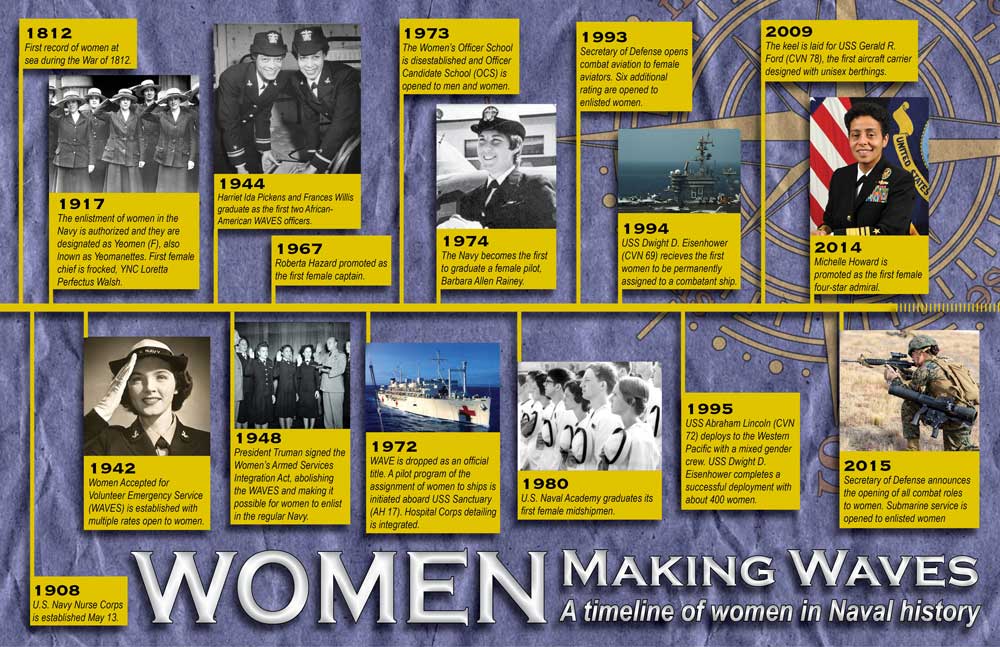

A graphic timeline illustrating the history of women in the Naval service. Photo illustration by Mass Communication Spc. Seaman Apprentice Gitte Schirrmacher, courtesy of the U.S. Navy.

“Major Shire, are you ordering me, a naval officer, to tell an Air Force officer to wear a different bra under a shirt?”

“Blouse, it’s called a blouse for females and shirt for men. But, in a word, yes.”

Shire came from behind the desk and leaned against it, crossing his arms over his spreading middle. “You need to talk to her because you’re both girls.”

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

I stood to meet his gaze. A retort died on my lips. I knew it was a lost cause. “I’ll speak with her today. Give her a payday or two, in case she needs to buy new, appropriately colored bras. They can be pricey.”

Maj. Shire blushed again. “Oh, I wouldn’t know.”

You’re telling me, I thought.

That night, I visited the errant officer whose suite was upstairs from mine in the officers’ quarters.

“Seriously? The major couldn’t even say ‘bra’?’” 2nd Lt. Davenport asked. We had a good laugh about the situation. We discussed other challenges of being minorities in the military over the Coronas I brought to assuage the reason for my visit.

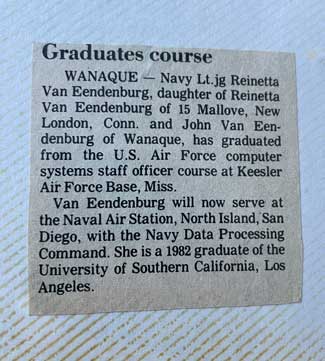

An announcement in R. Van’s hometown newspaper, the Bergen Record, on the completion of a computer course. Photo courtesy of the author.

Star reached for a beer. “The guys treat me like a china doll that might break at the first difficult tasking—even though I know the systems better than they do—or a doormat to be stepped on. They send a woman to talk to me if there’s any issue. Like they sent you.”

“I tell you, Star, I had to think about this underwear stuff. I’m white and I wear a white or nude bra in uniform.”

Star laughed. “I’ve been counseled to wear a black bra too. I don’t care; let me do my job.”

I nodded. “It’s growing pains like with any change, but I was sure the Air Force would be a model for human relations. I tell the sailors to treat women like sisters.”

Star agreed. “It’s not that hard. My three brothers were great. Mom insisted on us showing everyone respect. But they sure did tease me. And you?”

“My brother was more of a hitter than a teaser. I was speaking of brothers in general.”

Star patted my hand. “That’s rough. Didn’t your parents stop it?”

I shook my head. “No one believed me, even when I showed them my arm’s black-and-blue mark the size of an orange from his punches. My brother could do no wrong.”

“How about in the Navy?”

I shrugged. “I thought I was the only one getting hit on and bullied until I asked a woman at another command. She was a new lieutenant with similar encounters. From senior officers, officers in her chain of command, peers, even enlisted. Neither of us reported anything.”

“Yeah, I know,” Star said. “My previous command railroaded a woman—only on her first tour—and I don’t want it to happen to me. My career is too important.”

I finished my beer. “It’s still bogus, even with the Navy showcasing some convoluted system for reporting. The men know that they can get away with it.”

Star said, “Like the wolf guarding the hen house. But women hit on me too. In some ways, that’s even worse.”

I told her about being invited, with a very physical gesture, to join a three-way with a woman officer who was senior to me and a chief while I was in Hawaii for training. “I brushed it off, saying they had the wrong guy.”

A cartoon created by Navy Lt. Mary Beth Stowe, who served with R. Van in the early 1980s, that summed up many of their experiences. Photo courtesy of Mary Beth Stowe.

I told her about attending Tailhook, the annual drunk fest for Naval aviators. “I didn’t party with the flyboys. I relaxed by the pool with a woman pilot from my squadron.”

I told her about a senior officer who was my boss repeatedly haranguing me to drink with him—and who knows what else he had in mind. Finally, I went to the base chaplain and explained the conundrum.

Star took a sip of beer. “Did the chaplain help?”

I shook my head. “That man of the cloth gave the cloth on my thigh a squeeze and suggested we have an affair.”

“Did the chaplain really say that? To sleep with him so your boss would back off?”

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

“Yeah, it’s like a sitcom sketch, but it wasn’t funny then. Everyone was senior to me. There was no one to turn to. I mean if the minister wouldn’t even help me. …”

The young Air Force officer and I spoke as equals as we reflected on these tense situations, understanding such details would remain between us. We agreed there wasn’t much we could do to help other women; there were too few of us.

We shared the commitment to do our jobs and be good teammates, the ultimate goals for those spearheading change.

This War Horse reflection was written by R. Van, edited by Kristin Davis, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.