The USSR Called Operation Atrina a Triumph. We Knew It Was a Failure.

In spring 1987, the Soviet Union launched Operation Atrina, scrambling five Victor III-class submarines from their Kola base that raced toward U.S. Naval installations along the Atlantic coast. The USSR claimed its submarines were undetected. It was a lie then and it remains a lie today—and I can attest to this firsthand.

It’s no secret that conflict under the ocean raged during the Cold War. The USSR lagged in technology and tried to make up for it with sheer volume and submarines that were faster and could dive deeper. But they were noisy. Very noisy. And relatively easy to track.

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union developed a program to convert ocean-going fishing trawlers outfitted as electronic intelligence platforms. By the late 1970s, the latest Soviet spy ships also carried jamming equipment. These trawlers were a constant Cold War presence outside U.S. Naval bases. Photo courtesy of the author.

The Walker spy scandal—a devastating breach of security that went undetected for nearly 18 years—changed that. In the early 1980s, the USSR deployed the titanium-hulled Sierra and updated Victor III-class submarines. These vessels were significantly harder to track—and it was only possible at shorter ranges.

For its part, the USSR was eager to flex its newfound muscle and take it inside territorial waters and even carrier task forces. Its subs even penetrated Puget Sound in search of the ultimate prize: detecting and tracking one of the new, ultra-stealthy Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines. But even with this newfound brashness, the USSR usually made its probes with one submarine at a time.

* * *

When I sat in the classifier’s chair at the Military Entrance Processing Station in 1983, I didn’t know what I wanted to do in the Navy. I did know that I wanted something challenging and significant. In the gap between the Vietnam and Middle East conflicts, it didn’t seem like there were a lot of options for those seeking adventure.

“Would you like to become a storekeeper?” the classifier asked me.

“You mean work as a supply clerk?” I asked. “Sounds boring.”

“OK then, how about becoming a machinist mate?”

“Meh. My dad was a machinist mate. Sweating in hot, noisy engine rooms doesn’t sound like a lot of fun to me. What else do you have?”

The classifier continued his pitch. “We have a slot for a radioman, but you would have to graduate high school early.”

“That’s getting closer. But I would like to attend a full year of school. Let’s keep that as a backup.”

The classifier dug a little more. “Well, if you can pass the hearing test, you can be a submarine sonar technician and leave in June.”

Now this seemed interesting and challenging. I had only the vaguest idea what a sonar technician did, but the chance to be on the frontline of the Cold War was too good to pass up.

“I’ll take it,” I responded, and just like that, the next decade of my life was set into motion.

* * *

I left for Navy recruit training in 1984 and started working through the advanced electronics pipeline. I received my first active submarine assignment in early 1986—I was a “rider” on the USS Georgia SSBN 729. My job was to get qualified in submarines; in return, I would help the Georgia deploy with a full crew. Much of my sonar training involved learning about and being able to acoustically identify vessels of the Soviet navy—including submarines.

With all that training and zero days at sea, I eagerly stepped into my first prepatrol intelligence briefing. I don’t recall the specific details of that meeting and couldn’t share them if I did. But I did learn that multiple Soviet submarines were on station in their usual places in the Pacific. Soviet submarines were as predictable as they were detectable.

Once underway, we would receive regular radio updates providing us with approximate locations of Soviet submarines in relation to our designated patrol box. The mission of a Trident submarine was to “hide with pride,” and up to this point, no Trident had ever been detected by our archenemy. We focused on searching for enemy submarines; on that patrol, we had multiple tape recorders running as backup.

The USS Georgia SSBN 729 tied up to the USS Proteus AS-19 in Apra Harbor, Guam, in May 1986. Naval History and Heritage Command photo.

I can still recall the first time I detected a Soviet submarine. My heart pounded through my chest, my breath grew short, and I could hear a pin drop at a hundred yards. Never before or since have I experienced such intense focus—this was what all my training was for. This was the real deal.

The Georgia was chosen at random to participate in the first SSBN Continuity of Operations Program (SCOOP). In nearly four years of Trident SSBN patrols, every submarine had departed from and returned to Naval Submarine Base Bangor, Washington. SCOOP was designed to practice replenishment and crew turnover in forward-based ports. This was a game-changing move to counter Soviet attempts to track U.S. “boomers.” By resupplying in random and remote places, the Navy vastly increased the potential patrol area of a Trident submarine—making them exponentially more difficult to detect.

After a while, we made an unplanned stop at Pearl Harbor for an inspection. It was a warm, muggy spring day. In the distance, I saw an unfamiliar boat approaching us—a Soviet AGI under the guise of a fishing trawler. Make no mistake: This vessel was there to monitor vessel traffic coming and going from Pearl Harbor. If possible, it would also try to get details about American ships, including sound profiles on American submarines. As a counter to their attempts, we would always turn on noisy auxiliary equipment to mask any sound coming from the sub. The AGIs were an ever-present Cold War nuisance.

We finished our patrol in Apra Harbor, Guam, tying up to the USS Proteus (AS-19) submarine tender, a relic from World War II. From there, I flew to New London, Connecticut, where the pre-commissioning unit Nevada (SSBN 733) readied for sea trials. We came and went for a few days at a time for the next three months. Always waiting for us near the mouth of Connecticut’s Thames River was another Soviet AGI watching. And trying in vain to listen. Trident submarines aren’t just silent. They are often reported as sounding like a “hole in the ocean.” We would make our usual racket on the surface, submerge into complete silence, and evade them.

Shortly after commissioning on Aug. 16, 1986, we left Connecticut for good and headed toward Port Canaveral, Florida, for more testing and sea trials. From the pier in Florida, we loaded MK-48 exercise torpedoes and unarmed Trident C4 missiles. (The book Hostile Waters references a Soviet-type Delta III-class SSBN on patrol in their usual area off the coast of Florida during this same time.)

The USS Nevada running on the surface to leave port. Photo by Electronics Technician (Submarine) Petty Officer Second Class Randy Taylor, courtesy of the author.

We were made aware of the Delta and advised to steer clear of its patrol box as we came and went. On Sept. 30, 1986, we successfully launched a Trident SLBM test missile and returned to port. Three days later, the Soviet K-219 suffered an explosion and a fire in a missile tube near Bermuda. The K-219 was on its way to relieve the Delta we were warned about. The K-219 subsequently sank under tow and several crewmen died. Russia blamed the United States—and we denied involvement in the incident. The Nevada was in port, and I read about the incident in the local newspaper.

We returned to Florida in February to take the Nevada into post-shakedown availability. PSA was like the 10,000-mile checkup for the sub before it could be loaded up with nuclear weapons and begin deterrent patrols.

And this is where things start to get interesting.

* * *

At the time, critics of President Reagan’s defense spending tried every tactic they could think of to reduce costs—and the hefty price tag of Trident submarines was at the top of everyone’s list. Up to this point, all Tridents had been constructed by the General Dynamics Electric Boat shipyard in Groton, Connecticut. Congress wanted to introduce competition between shipbuilders to try to lower costs, and we would be the guinea pig. The Newport News Naval Shipyard and Drydock company in Norfolk, Virginia, would perform the PSA on the Nevada—the first time Newport News touched a Trident submarine.

Sitting on the pier in Port Canaveral, we didn’t know what to expect in Virginia. But our first order of business was to remove all warshot torpedoes off the submarine; they weren’t allowed in the shipyard. Upon completion, we topped off our food supply and headed north—unarmed.

The objectives of a PSA included fixing everything that was broken, testing every shipboard system, and installing some new, leading-edge equipment. We were given a budget and ambitious dates to complete all this work.

All eyes were on us, from the president to members of Congress and the chief of naval operations. Determined to make this a success, our executive officer came up with the slogan “On Time or Ahead of Schedule” as a motivation to keep us focused.

For more than 45 straight days we had our heads down working long hours to the point of exhaustion. Then one afternoon, the wardroom and sonar division were called into an intelligence briefing. Here we learned about an unusual flurry of submarine activity from the Soviet Kola submarine base.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

Kola is a bit east of Finland in the Barents Sea.

“What does this have to do with us?” I asked.

“Nothing,” we were told. But five Victor III class submarines leaving port at the same time was highly unusual.

The Victor III submarine was the most capable anti-submarine warfare platform in the Soviet fleet and was the bane of our existence. But they were so far away. They couldn’t be a threat, right?

A few days later, we were called back into the briefing room for an update. “Remember those Victor IIIs we told you about?”

Of course we remembered.

“They’re all pointed directly toward Norfolk, trying to get there as fast as they can. They could be off the coast of Norfolk in 72 hours.”

We were 48 hours from getting underway.

This concerned us. We didn’t know their intentions. We had to transit from Florida back to Port Canaveral, and we were unarmed. A sitting duck. But why would they have an interest in us? There were plenty of reasons. A Trident had never been detected. If a Victor could detect us, it would be a huge triumph for the USSR—and our eternal shame.

More importantly, the first seven Tridents were exactly the same. The Nevada was slightly different. Not only that, we had new equipment installed in Newport News that would make us a more capable anti-submarine warfare platform. We were now the biggest prize in the U.S. Navy. Tracking us would be a huge Cold War victory. And if we happened to have an “accident” and never make it back to Florida—even better.

We didn’t panic, but we left the briefing with a grim determination to slip out of Norfolk as quickly as possible and try to beat the Victors before they even showed up.

The commanding officer of the USS Nevada SSBN 733 hands a commendation to Sonar Technician (Submarine) Petty Officer First Class David Chetlain. Photo courtesy of the author.

We left Newport News early on an April morning with no fanfare or announcement—as is usual with submarine operations. The AN/BPS-15 radar was turned off—its electronic signature was unique to Tridents and we wanted to keep our profile as low as possible. But for all of our secrecy, the Soviet AGI was right there waiting for us as we made our exit.

We employed our usual tactics to evade it, but the cat was out of the bag. Certainly, the AGI would have notified all the Victors that we’d left port. Unarmed.

It is no big secret that the Gulf Stream sends warm water north up the Atlantic coastline. This wreaks havoc on sonar performance. “A submarine detected in the Labrador Current but crossing the Gulf Stream has been compared to a person going out of an open field and disappearing into the nearby woods,” according to Principles of Underwater Sound.

The Victor IIIs made it across the Atlantic—but they may not have been prepared for this final hurdle in their mission.

We submerged as soon as the water was deep enough and took “hide with pride” to new levels on our journey south. The ship was rigged for “ultraquiet” as soon as we slipped beneath the waves. All unnecessary machinery was shut down to reduce our noise signature. We moved in and out of the Gulf Stream to find the optimal sound profile for evasion and constantly changed depth to stay on the opposite side of the thermal layer.

Did we detect any of the Victor IIIs? Maybe. American anti-sub warfare forces knew where they were.

The USSR called the Atrina operation a triumph. We knew it was a failure.

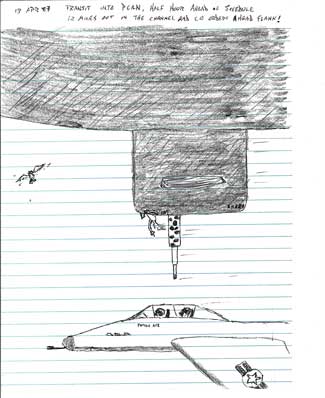

When the USS Nevada surfaced for its final transit into Port Canaveral, Capt. Rohm ordered a “flank bell” to arrive in port 30 minutes ahead of schedule. The crew was amused, and it inspired Jim Gover to create this doodle. Photo courtesy of the author.

Once we turned toward Port Canaveral, we surfaced for the final stretch of our journey. We had been ahead of schedule for the entire PSA and the commanding officer wanted to continue. He ordered up a flank bell and we sprinted the last few miles at top speed into port. We arrived 30 minutes ahead of schedule and breathed a big sigh of relief.

By the time we flew home, I had only been going to sea for about 16 months. In that time the Soviet navy was a constant presence, mostly routine but, as Atrina proved, occasionally unpredictable.

Despite the ultimate failure of Atrina, the increasing Soviet capabilities were a legitimate and serious concern. We knew they were closing in on us. U.S. Navy Admiral Kinnaird McKee predicted the future when he said, “Eventually, U.S. and Soviet submarine capabilities will converge. … It will be blind man’s bluff with other submarines.”

We observed a sharp dropoff in the Soviet presence following Atrina, but I didn’t think much of it. I was on patrol 30 months later when the Berlin Wall fell, and I did think a lot of that—it was the biggest of deals. I can still remember reading the radio message and wondering, “What happens next?”

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

My last patrol encompassed the duration of Desert Storm, after which the USSR dissolved completely and the United States entered a new era.

From the time I sat in that classifier’s chair until 1991, the world had changed in unforeseen ways. My contributions were mostly insignificant, but Atrina always sticks in my mind. It was the USSR’s last attempt to project power across the Atlantic, and it failed.

NATO forces had tracked the pride of the Soviet fleet from the moment they left port.

We won without firing a shot.

This War Horse reflection was written by David Chetlain, edited by Kristin Davis, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headline.

Comments are closed.