In That Moment I Learned My Service to This Country Could Not Transcend My Skin Color

I still remember the blinding glare of police lights in my rearview mirror. My heart began to race as the white officer approached my vehicle. I knew I did nothing wrong, but still I clenched the wheel tightly to signal I was not a threat. I was unsure what would happen next.

During my second year on active duty in the Air Force, I’d volunteered as a Sober Ride driver. It was in this moment—two hours away from where Ahmaud Arbery would meet his tragic fate 10 years later—that I learned my service to this country could not transcend my skin complexion.

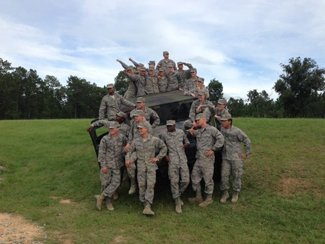

“Raising my right hand to serve the world’s greatest Air Force could not insulate me from the harsh realities felt within my community,” writes Jimmy Anderson. Photo courtesy of the author.

Before ride-sharing apps like Uber, Air Force bases launched Sober Ride to tackle the surge in service member alcohol-related incidents. The program relied on volunteers who added their names to a call roster for weekend duty. As a participant, I was called to pick up fellow active-duty members from local bars to ensure their safe return.

On this night, after receiving a call during the late hours, I left my dorm room in flip-flops and pajamas to pick up two intoxicated airmen. In the dead of night, near Moody Air Force Base, my role as a volunteer sober rider took a disconcerting turn. After picking up the two noncommissioned officers, I headed down the main road between their house and the base.

A missed turn prompted me to make a U-turn, which triggered the ominous glow of police lights. I pulled over and we prepared for routine checks, showing the deputy sheriff our military IDs. I calmly explained my volunteer duty and offered to contact the Moody Air Force Base Sober Ride manager but was met with reluctance from the officer.

A second officer was called and arrived, which raised tensions for all three of us. Ignoring protests from the two white noncommissioned offers, the deputy sheriff and second officer—both of them white—told me to exit the vehicle and instructed me to perform a series of field sobriety tests. I passed, of course, and the deputy told me to return to the car.

Capt Jimmy Anderson, right, receives an award from Lt Gen. Joseph Thomas Guastella Jr. Photo courtesy of the author.

Fifteen minutes later, he asked me to get back out again. This time, the noncommissioned officers asked if they could get out as well. Both cops told them to stay in the vehicle. Then one of them walked me to the back of the car, which made me nervous—and I began to question whether I’d done something wrong.

He pointed to my license plate and indicated that the black border surrounding my plate should never cover the plate’s county; after the hour-long ordeal, he issued a warning.

This unsettling experience echoed childhood tales of police harassment and revealed an upsetting reality.

Jimmy is a career Intelligence Officer who currently serves in the Air Force Reserve stationed at the Pentagon. Photo courtesy of the author.

Growing up Black in South Carolina, I often heard stories about police brutality and harassment against Black protestors during the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. One particular story from Orangeburg, South Carolina, involved student protestors who were sprayed with fire hoses and tear gas after refusing orders to disperse. Three hundred eighty-eight students were arrested; after the jail was filled, many were placed in an outdoor stockade.

Eight years later, in that same town, South Carolina Highway Patrol officers fired their weapons into a crowd of Black student protesters, killing three and injuring another 28. Although it received little national attention, it was known across South Carolina as the Orangeburg Massacre and was among the stories relayed to me in childhood.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

At age nine, I watched reruns of the Rodney King beating. At 16, I read the story of Kathryn Johnston, an elderly Black woman shot by police in her own home in Atlanta, Georgia, as they executed a search warrant based on false information. I learned about the devastating impact of no-knock warrants on the Black community.

Jimmy Anderson, right, with Blue Star Families at the 75th anniversary of the Executive Order 9981 symposium. Photo courtesy of the author.

It should come as no surprise that, against the backdrop of these stories, I was raised to cooperate with the police and never talk back, to turn down my music when police were nearby, and so much more.

To this day, I replay the time I was stopped and questioned by the police based on racial profiling and mistaken identity. I was six months away from entering basic training. I will never forget Anthony Hill, a fellow airman and friend who I deployed with to Afghanistan and who was shot and killed by police outside his apartment complex in Georgia. Not long after, I learned of the story of Sgt. Isaac Woodard, who was beaten and blinded by police after serving his country for more than three years in the Pacific during World War II. Woodward had just been discharged from the Army and was still wearing his uniform when he was attacked.

Jimmy Anderson poses with Medal of Honor recipient Melvin Morris in the White House State Dining Room after Col. Paris Davis Medal of Honor Ceremony. Morris, a Green Beret, was recognized decades after his heroic actions in Vietnam after a Congress-mandated review of service records from earlier wars to determine whether any of those men had been passed over for the nation’s highest medal for valor because of discrimination at the time. Photo courtesy of the author.

I thought such a reality would end when I took an oath to serve. It didn’t. Raising my right hand to serve the world’s greatest Air Force could not insulate me from the harsh realities felt within my community.

Yet the unequal treatment and harassment of Black service members in the communities in which they live and serve are rarely discussed. Acknowledging these experiences—and sharing them—is crucial. We must reflect on the hidden costs of sacrifice endured by service members of color and their families.

My experience outside Moody Air Force Base during my second year of active duty forced me to confront the reality that military service does not serve as a shield against such events. My service could not transcend my skin complexion.

We must create space for Black service members and other service members of color to tell their stories. The leaders of military installations can take action to capture the negative experiences faced by service members and their families during their time “on station” and in the community. Community-based organizations that advocate for service members, veterans, and their families can also play a role in amplifying these concerns.

Jimmy Anderson, left, on the state floor of the White House on the day President Biden signed the PACT Act into the law. Pictured with Jaime Harrison and Army National Guard Lt. Col. Clay Middleton. Photo courtesy of the author.

Despite the prevailing narrative that issues of inequity are relics of the past, stories like mine and others—like the case of a uniformed U.S. Army lieutenant who was threatened by police at gunpoint and pepper-sprayed through his window during a 2020 traffic stop in Windsor, Virginia—remind us that there’s still work to be done.

As we commemorate Black History Month, let’s not forget the sacrifices made by service members who, at some point, found themselves in the shadows of American society yet continued to wear the uniform. Let’s honor not only the service of Black veterans, but the individuals and families who bore the weight of service, transcended the challenges, and created a legacy that contributed to generations of service.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

The end of my story is perhaps the most eye-opening. When I finally dropped off the two white noncommissioned officers, they apologized profusely for what the deputy sheriff put me through. They openly expressed that this was the first time they’d seen police harass a Black person. They said we have a long way to go in this country.

I believe they walked away with a greater understanding of the cost of sacrifice for so many service members who look like me.

This War Horse reflection was written by Jimmy Anderson, edited by Kristin Davis, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.